Category: Iowa

Let’s Have an Iowa Potluck with a Side of History!

Dubuque is home to some of Iowa’s most distinctive culinary traditions, from turkey dressing sandwiches to the memorable meals served at the iconic Hotel Julien Dubuque. We’re going to be eating up all this local flavor at a potluck on Sept. 7 at the Carnegie-Stout Public Library in Dubuque, starting at 5:30 p.m., followed by my “Culinary History of Iowa” program—and you’re invited!

Click here for all the details.

In meantime, here’s a sample of some classic Dubuque recipes to tempt you. These recipes come from a variety of sources, including two cookbooks (including The Flavor of Dubuque and Another Flavor of Dubuque) compiled by The Women’s Auxiliary of the Dubuque Symphony Orchestra. Not only do those cookbooks include tried-and-true local recipes, but they feature many photos of local landmarks. The third cookbook (Cedar Ridge Farm Recipes) appears to have been a collection of family recipes, and librarian Sarah Smith isn’t sure how it came to be in the Carnegie-Stout’s collection, but it’s charming.

Thanks, Sarah, for sharing these recipes and offering us a true taste of Dubuque!

One more thing–if you’re in Dubuque, stop by Cremer’s Grocery, a Dubuque classic since 1948, for their famous turkey dressing sandwiches and other goodies! Also, here are some fun facts about Dubuque, an All-American City that’s truly a “Masterpiece on the Mississippi:”

- Dubuque was settled by a French Canadian fur trader in the late 1700s named Julien Dubuque. In those days, Dubuque was known as the “gateway to the west.” Lead mining soon became the mainstay of Dubuque.

- There has been some type of hotel on the site of the Hotel Julien Dubuque since 1839.

- Some cool things to see in Dubuque include the National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium, along with the Fenelon Place Elevator Company, which is the world’s shortest, steepest elevator ride!

Source: American Realty

The Flavor of Dubuque (published 1971)

Page 26

Derby Grange Steak. The present owners of what was the main farmstead in the area west of Dubuque long known as Derby Grange found this recipe behind an old picture of President Harding left by the previous owners. Cut 1 thick round steak into 1-inch pieces. Pound very thin and sprinkle with flour, salt, pepper, a little cumin and dill. Poud again and brown pieces on both sides in a little butter or other fat. Place in baking dish and pour over 1 cup tomato sauce. Bake, covered, at 300 degrees for 1 hour. Serves 7. Can be frozen. -Joan Mulgrew

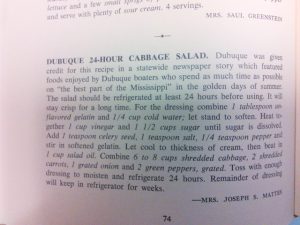

A Dubuque original –24-Hour Cabbage Salad

Page 74

Dubuque 24-Hour Cabbage Salad. Dubuque was given credit for this recipe in a statewide newspaper story which featured foods enjoyed by Dubuque boaters who spend as much time as possible on “the best part of the Mississippi” in the golden days of summer. The salad should be refrigerated at least 24 hours before using. It will stay crisp for a long time. For the dressing combine 1 tablespoon unflavored gelatin and 1/4 cup cold water; let stand to soften. Heat together 1 cup vinegar and 1 1/2 cups sugar until sugar is dissolved. Add 1 teaspoon celery seed, 1 teaspoon salt, 1/4 teaspoon pepper and 1 cup salad oil. Combine 6 to 8 cups shredded cabbage, 2 shredded carrots, 1 grated onion and 2 green peppers, grated. Toss with enough dressing to moisten and refrigerate 24 hours. Remainder of dressing will keep in refrigerator for weeks. -Mrs. Joseph S. Mattes

More recipes from Dubuque, Iowa

Another Flavor of Dubuque (published 1983)

Page 70

Welsh Rarebit. Shred 1/2 pound Cheddar cheese, put in double boiler and let melt slowly over hot water. Keep water below boiling point. Add 1/4 teaspoon dry mustard, paprika, salt and a few dashes cayenne pepper. Stir in 1 cup milk or cream and 1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce. Mixture should be smooth and velvety. Serve on hot buttered toast. Strips of bacon are especially good over this.

Welsh Rarebit became a traditional Sunday night supper in the girls’ boarding school at Sinsinawa Mound (this is technically across the river in Wisconsin, but many of the students would have been from Dubuque.) The recipe’s simplicity and flexibility accommodated the varying number of returning students each Sunday night. It was sometimes served over tomatoes or ham. -Bette F. Schmid

Page 156

Dubuque Symphony Orchestra Auxiliary English Toffee. This delicious toffee was sold at the 1981 Designer Showcase, and the Auxillary has had many, many requests for the recipe. Line cookie sheet with foil. In heavy pan mix 1 cup sugar, 1/2 pound butter, 1/4 cup water, 1/4 teaspoon salt, 1/2 teaspoon vanilla and 1 cup chopped pecans. Cook quickly over medium high heat, stirring constantly, to a rolling boil. Cook to hard crack stage, 300 degrees on candy thermometer. Pour on cookie sheet. Cool and break into pieces. Store in air tight container. Do not freeze, refrigerate or make substitutions in recipe. -Mary Stauffer

Cedar Ridge Farm Recipes by Rita Tarnutzer Montgomery (published 1999)

Page 69

Chocolate Chip Cookies (Monster Cookies)

1/2 cup margarine

1/2 cup shortening

1 cup brown sugar

1 cup white sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla

2 eggs

1 cup oatmeal

1 cup corn flakes

2+ cups flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon baking soda

12 ounces chocolate chips

Bake for 10-12 minutes at 350 degrees.

NOTE from Rita: For Monster Cookies, form into 5 oz. balls and flatten into 7-inch diameter circles, two to a cookie sheet. Bake for about 14 minutes at 350 degrees. Makes 8 cookies.

In 1976, when Al had his first antique shop, on 16th and Central Ave., he had a huge glass cookie jar. His idea was to display a couple of really big cookies in it. Everyone wanted to buy them! So, I began baking these monster cookies, 32 at a time and selling them for twenty-five cents each. (They cost twelve cents each to make.) I couldn’t keep up with the demand, so he raised the price to thirty-five cents and still they sold. School kids stopped on their way home from school and bought a cookie to share!

Page 159

Turkey & Dressing Sandwiches

from Janet Duscher, 12/88

Bake in a covered roaster until meat falls from bones: 1 – 12 lb. turkey

Remove meat from bones and chop.

Cook together:

1 1/2 cups cooking juices

3/4 cup margarine

2 1/2 cups chopped celery

3 medium onions, chopped

2 tablespoons sage

2 teaspoons poultry seasoning

1 – 1 ½-ounce package dry onion soup mix

1 – 10 3/4 ounces cream of chicken soup

Cube: 2 loaves of day-old bread (about 6 quarts)

Stir together bread cubes, juices with vegetables and seasonings and turkey.

Bake in a greased pan at 350 degrees until heated thoroughly, about one hour.

Serve hot in buns.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you want more more intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Feel free to share this information with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

About me:

Some people know me as Darcy Dougherty Maulsby, while others call me Yettergirl. I grew up on a Century Farm between Lake City and Yetter and am proud to call Calhoun County, Iowa, home. I’m an author, writer, marketer, business owner and entrepreneur who specializes in agriculture. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com.

Busting the Iowa Butter Gang

“Hey, did you ever hear of the Iowa Butter Gang?” It’s the last question I expected to hear during my recent “Culinary History of Iowa” book signing in West Des Moines, and it definitely caught my attention.

It came from Jan Kaiser, a former Des Moines librarian who had first “encountered” the nefarious gang a few years ago through research into 70+-year old newspaper archives.

Turns out that crime came in many forms during the Great Depression. Back then, butter was big business in rural Iowa. Not only was Iowa a leading dairy state, but hundreds of Iowa creameries produced high-quality butter that helped make Iowa a top shipper of butter into the New York City area, I learned recently from Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Bill Northey.

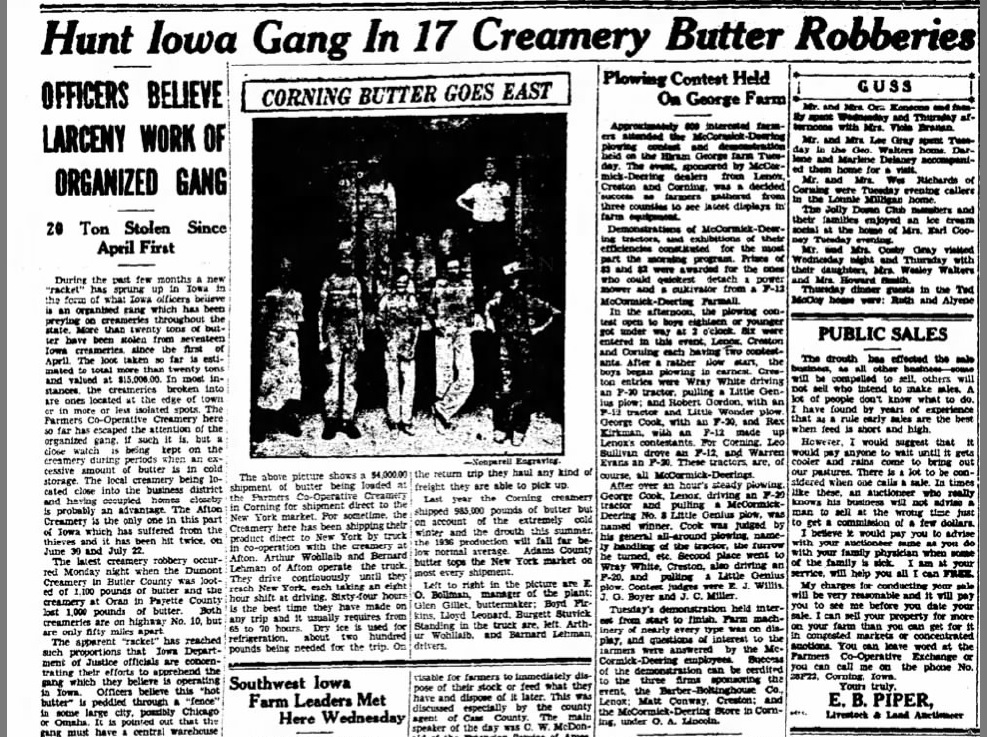

While some Depression-era criminals robbed banks, some thieves in rural Iowa opted to rob creameries. A headline in the Aug. 6, 1936, edition of the Adams County Free Press newspaper announced, “Hunt for Iowa Gang in 17 Iowa Creamery Butter Robberies: Officers Believe Larceny Work of Organized Gang.”

The article noted that during the spring and summer of 1936, a new “racket” had sprung up in Iowa in the form of an organized gang that preyed on creameries throughout the state. By early August 1936, more than 20 tons of butter had been stolen from 17 Iowa creameries since early April 1936. “The loot taken so far is estimated to total more than 20 tons and is valued at $15,000,” noted the news article.

In most cases, the creameries that were broken into were located on the edge of town or in isolated spots. The gang’s targets in 1936 included:

• April 3, Palmer, 2,172 pounds

• April 8, Fenton, 3,440 pounds

• May 15, Fenton, 2,080 pounds

• May 28, Edgewood, 630 pounds

• June 4, Britt, 5,184 pounds

• June 12, Kimballton, 4,000 pounds

• June 20, Coulter, 4,095 pounds

• June 30, Afton, 2,200 pounds

• July 1, Hampton, 2,209 pounds

• July 3, Hubbard, 7,488 pounds

• July 8, Palmer, 3,553 pounds

• July 11, Randall, 2,304 pounds

• July 22, Afton, 2,764 pounds

• July 30, Nashua, 1,500 pounds

• July 31, Masonville, 2,228 pounds

• August 3, Dumont, 1,100 pounds

• August 3, Oran, 1,000 pounds

“It is believed that before each burglary, the creamery is selected by the gang and careful plans made,” stated the Adams County Free Press. “The robbers are evidently expert burglars and experience little difficulty in breaking into creameries. They use a truck and are gone with their loot before local officials know there has been a burglary.”

Butter making was big business in small-town creameries across Iowa in the 1930s, including this creamery in Somers (featured in my Calhoun County book). George Smith built Somers’ first creamery was built in 1900. In 1913 S. P. Petersen purchased and updated the creamery, which became a major business in town for many years. The round tubs in this photo each held 65 pounds of butter. This butter was sold to area stores. In Fort Dodge alone, about 2 tons of butter was sold each week. Butter from Somers was also sent to New York.

Peddling “hot butter”

The writer speculated that the gang must have a central warehouse, since butter is highly perishable. The apparent racket reached such epic proportions that Iowa Department of Justice officials concentrated their efforts to apprehend the gang. “Officers believe this ‘hot butter’ is peddled through a ‘fence’ in some large city, possibly Chicago or Omaha,” the writer noted.

(A fence is someone who knowingly buys stolen property for later resale, sometimes in a legitimate market. The fence acts as a middleman between thieves and the eventual buyers of stolen goods who may not be aware that the goods are stolen.)

The article continued, “The Farmers Co-operative Creamery here [in Corning] so far has escaped the attention of the organized gang, but a close watch is being kept on the creamery during periods when an excessive amount of butter is in cold storage.”

It’s no wonder locals were keeping a close watch. The Farmers Co-op Creamery shipped thousands of dollars of butter each year to the New York market. The Adams County Free Press reported that two local truck drivers would each take eight-hour driving shifts and drive straight through from Iowa to New York. The best time they made from Iowa to New York was 64 hours, although the trip usually took 65 to 70 hours.

About 200 pounds of dry ice were used for refrigeration during the trip. On the return trip, the drivers hauled any kind of freight they were able to pick up. In 1935, the Corning creamery shipped 985,000 pounds of butter, noted the newspaper article. Due to the harsh winter and summer drought of 1936, however, that year’s production was expected to fall far below average—a fact that made the butter robberies of 1936 even more devastating in rural Iowa.

Finally—a big break in the case

By August 1936, officers with the Iowa State Patrol (formed just a year earlier in 1935) and a group of northern Iowa vigilantes and deputy sheriffs had been driving the secondary and dirt roads nightly for the last two months, trying to catch the butter gang, according to the Des Moines Tribune (the capital city’s afternoon newspaper that ended in 1982).

Some promising leads ended in disappointment. In the summer of 1936, officers arrested Harvey Mighell of Holstein on suspicion that he was connected with the butter gang. He was taken to Audubon, where he was questioned and later released under $2,000 bond. Mighell denied having anything to do with the Iowa butter thefts.

Law enforcement officials got a big break, however, by late August 1936. A headline in the Aug. 29, 1936, edition of the Des Moines Tribune proclaimed “Iowa Butter Gang Crushed.”

Turns out an Omaha gang of six men and one woman stole some $30,000 worth of butter, cheese and eggs in a string of more than 30 robberies across Iowa in 1936. (The pilfered dairy products were worth nearly $525,000 in today’s money.) The butter was trucked to Omaha and was sold through a fence.

“Virtually every sheriff in northern Iowa has been on the case as well as several detectives of the Omaha police department and other Iowa town police departments,” the reporter noted.

Iowa prosecutors charged the gang with 32 robberies. Detectives recovered 70 tubs of butter, the Tribune reported, 66 of which had been stolen from a creamery in Wesley. All the cheese was lifted from Ionia, the story reported. Law enforcement officials took the dairy products and sold them through legitimate channels to packers in Omaha.

“Capture of the Butter Gang was the climax of one of the greatest Iowa manhunts in recent years,” officials told the newspaper.

One more try?

The story wasn’t over, though. Less than five years later, one of the original butter gang members tried to revive the scheme. Under the headline “Butter Theft Gang Thwarted,” the Jan. 15, 1941, issue of the Mason City Globe-Gazette reported the arrest of Bryon Green, 32, of Sioux City. “R.W. Nebergall, chief of the Iowa Bureau of Investigation, believed that Green was attempting to set up a new ‘butter theft gang’ in Iowa,” stated the article.

On Dec. 13, 1940, Green had been released from prison in Stillwater, Minnesota, after serving three and a half years for burglary. Within a few weeks of his release from prison, Green was arrested by Chicago police, who accused him of entering the Masonville, Iowa, creamery on January 9, 1941, and shipping 1,230 pounds of stolen butter to a Chicago firm.

Thus ended the saga of the infamous butter gangs that terrorized rural Iowa in the 1930s. Their nearly forgotten story faded into history, along with the small-town creameries that once inspired their notorious crime spree.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you want more more intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Feel free to share this information with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

About me:

Some people know me as Darcy Dougherty Maulsby, while others call me Yettergirl. I grew up on a Century Farm between Lake City and Yetter and am proud to call Calhoun County, Iowa, home. I’m an author, writer, marketer, business owner and entrepreneur who specializes in agriculture. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com.

The Lytton Cooperative Creamery Association (featured in my Calhoun County book) was organized in June 1933. Capital for the new venture came from local farmers, who subscribed for shares on a basis of $5 per cow. In 1936, the creamery produced 110,000 pounds of butter. Grade A milk was processed, bottled, and distributed under the name “Lytton Maid” until this was discontinued in 1963. The plant closed in August 1979.

Remembering Ambassador Branstad’s Legacy from the 1980s Farm Crisis in Iowa

A morning talk-show host on WHO Radio in Des Moines posed an interesting question when former Iowa Governor Terry Branstad was confirmed as the U.S. ambassador to China on May 22, 2017. The broadcaster asked what might define Branstad’s enduring legacy, and he suggested it may be Branstad’s service during the 1980s Farm Crisis.

The more I thought about it, the more I agreed. I was just a kid in the 1980s Farm Crisis and didn’t really understand what was happening, but I knew it was bad. I remembering writing a poem about the Farm Crisis in 7th grade in 1987 for my contribution for a time capsule that was buried in Lake City.

Sheltered as I was from my family’s financial realities, I had no idea my dad only made $800 one year during the peak of the Farm Crisis. Still, that was far better than what some other farmers were experiencing. As one farmer told me during a recent interview about his family’s Century Farm, the thing he dreaded the most during the Farm Crisis was the phone ringing. “You never knew who it might be or what bad news it might be,” he said.

The Farm Crisis was just starting its brutal transformation of Iowa agriculture when Terry Branstad was first elected governor of Iowa in 1982. This new era was a far cry from the heady go-go days of the 1970s, when agriculture was booming, and making good money in farming was not only possible, but almost easy.

Farmers were hurting

By the early 1980s, however, a combination of national and international factors, including a Federal Reserve Board policy of high interest rates to fight inflation and a grain embargo against the Soviet Union, devastated the farm economy. Crop prices to dropped below the cost of production. Land values plummeted. Countless rural Iowa banks closed.

“All of us who lived in Iowa at the time saw friends and neighbors lose their family farms and struggle with what to do next to earn a living,” said Iowa Sen. Charles Grassley, who recalled the Farm Crisis in a 2015 press release he issued about Branstad becoming the longest-serving governor in the nation’s history.

By the time Branstad took office as governor, individual farmers across the state were hurting. No one really wanted to believe it was as bad as it was, but agriculture was in serious trouble.

In early December 1985, an eastern farmer who was apparently distraught over his finances killed the president of his bank, his neighbor and his own wife before he killed himself. Dale Burr, 63, who farmed near Lone Tree, made national headlines after he walked into the Hills Bank and Trust Company and shot its president, John Hughes, with a 12-gauge shotgun.

With farmers in desperate need of help, the Iowa governor’s office created the Rural Concern Hotline to provide assistance where possible. The state tried to help producers with debt restructuring as much as it could.

As the Farm Crisis deepened by the mid-1980s, however, one of the biggest frustrations was the seeming indifference from officials in Washington, D.C. “President Reagan was very supportive and sympathetic,” Branstad recalled in an Iowa Public Television documentary about the Farm Crisis. “Unfortunately, David Stockman, who worked for him and who was the director of the Office of Management and Budget, was pretty cavalier in his attitude. Considering all the stress and challenges we were going through in Iowa, we didn’t just take no for an answer.”

As the Farm Crisis deepened by the mid-1980s, however, one of the biggest frustrations was the seeming indifference from officials in Washington, D.C. “President Reagan was very supportive and sympathetic,” Branstad recalled in an Iowa Public Television documentary about the Farm Crisis. “Unfortunately, David Stockman, who worked for him and who was the director of the Office of Management and Budget, was pretty cavalier in his attitude. Considering all the stress and challenges we were going through in Iowa, we didn’t just take no for an answer.”

Hollywood goes to Congress, Branstad creates a new environment for business

Even Hollywood took note. Two popular films, Country and The River, drew the eyes of America to the plight of the nation’s farm families. Soon, Hollywood stars like Jessica Lange were testifying before Congress about the Farm Crisis.

Far from Congress and Hollywood, however, Branstad relied on his small-town and farm background to lead Iowa through the Farm Crisis.

“The state needed men and women with vision and ambition to pull the economy out of the doldrums,” Grassley noted. “It needed people who could see the potential for farmers to add value to their operations and for Iowa to diversify its economy. Terry Branstad was one of those people.”

Branstad was at the forefront of creating a new environment to do business. He welcomed and actively encouraged innovation that would capitalize on Iowa’s bedrock work ethic and strong schools. As a result, agriculture continues to be a mainstay of the Iowa economy while providing the economic engine that benefits many other employment sectors, including renewable energy, manufacturing, crop research and much more.

Ironically, some of Branstad’s actions in the Farm Crisis didn’t seem that significant at the time but would benefit agriculture decades in the future. In 1985, while still in his first term as governor, Branstad welcomed Xi Jinping, who was then a Communist party official and feed cooperative director from Hebei Province. Xi Jinping, who is now the president of China, spent several days in Muscatine in 1985 leading a delegation of Chinese government officials who saw Iowa agriculture first-hand and became acquainted with Iowa farm families.

That visit 32 years ago forged an unlikely bond between China and rural Iowa that endures today. I believe this bodes well for rural Iowa and our role in the global economy as Branstad serves as America’s ambassador to China.

It’s also a large feather in the cap of an Iowa farm kid from Leland, population 284, whose legacy as Iowa’s governor and ambassador to China can’t be told accurately without looking back to those painful, pivotal days of the 1980s Farm Crisis.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you want more more intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Feel free to share this information with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

About me:

Some people know me as Darcy Dougherty Maulsby, while others call me Yettergirl. I grew up on a Century Farm between Lake City and Yetter and am proud to call Calhoun County, Iowa, home. I’m an author, writer, marketer, business owner and entrepreneur who specializes in agriculture. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com.

This column first appeared in Farm News in June 2017.

How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service

It shocked me the first time it happened. I was sitting in the living room of a World War 2 veteran and was interviewing him for a Memorial Day story. I felt humbled and grateful to hear his stories as he described the places he’d served, the hardships he had experienced, his fears and his perspective on life all these years later. What stunned me was his family’s reaction.

“That’s the first time I’ve heard most of those stories,” said his daughter who had stopped by during the interview.

This wouldn’t be the first time I’d have this experience. I’ve discovered that sometimes veterans won’t open up, even to loved ones, because the memories are too painful, but sometimes the reasons are much simpler. “I tried sharing these stories a few times, but my family didn’t really understand what I was talking about and didn’t ask any questions, so I just gave up,” one Iowa veteran told m e. “I decided it would be easier to talk about these things with other veterans.”

e. “I decided it would be easier to talk about these things with other veterans.”

This got me thinking—what’s the right way to talk to veterans, whether you want to thank them or hear more of their stories? If you’re like me, maybe you’re not even sure how to start the conversation.

That’s why I asked Marine Corps veterans James Nash and Jay Lippmeier for their insights. I first connected with Nash and Lippmeier after they came to Lakota, Iowa, for Hunting with Heroes. This amazing program, which was created by Bernie and Jason Becker, invites Marines from the Wounded Warrior Battalion at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, to the Midwest each November for an all-expenses-paid trip to find some peace in the Iowa countryside and enjoy some prime pheasant hunting.

Captain Nash is now retired from the Marine Corps and lives in Oregon. He enjoys returning to Iowa to help create a sense of camaraderie and comfort for the Marines who participate in Hunting with Heroes for the first time. Staff Sergeant Lippmeier, who participated in the 2016 Hunting with Heroes event, is a Cincinnati, Ohio, native who recently retired from the Marines Corps and appreciates the chance to spend more time with his family, including his children.

I’d like to thank Captain Nash and Staff Sergeant Lippmeier for their friendship and for letting me share their insights in my May 26, 2017, Farm News column, which I’m also sharing here:

Q: Any tips on what people can say to veterans to start the conversation?

Nash: When folks say thanks for your service, it does two things to me. I typically sense their gratitude, but I also sense that sometimes people issue that canned phrase to reassure their sense of patriotism to themselves, and they are not interested in what exactly it is they’re thanking me for.

When I talk to vets, I ask then what branch they were in and what their job was. Army vets often respond with a numerical designation for their military occupational specialty (MOS), like 11B. That’s fine, but ask what that means, where were they stationed, what unit did they serve with? Did they deploy? Do they still keep in touch with anyone they served with?

If these questions don’t begin a conversation, the veteran likely doesn’t want to talk. Respect that. That’s the time to end the conservation and say thank you. It won’t be hollow because, now you both know what you are thanking the veteran for.

Lippmeier: Treat veterans like other people you’ve just met. Ask them what they do/did in the military, like their branch of service and their military occupation. Then use follow-up questions, especially if you don’t understand the answers or certain verbiage the military uses. I would much rather explain something to someone than have them have no clue what I’m talking about.

Upon first meeting someone, most vets I know have no problem talking about what branch they were in or what job they did without going into a lot personal details. Most vets will start to open up a bit as they get more comfortable. If someone doesn’t want to talk about his or her service, respect that. Everyone has bad days sometimes.

Q: Are there any things people shouldn’t ask?

Nash: I don’t like when folks asked me how many people I killed. It’s not like I wrote hash marks in my journal. But if they do ask, that’s better than if they are afraid to ask. When I sense people don’t have the courage to ask about my experiences, it makes me compare that lack of courage to the bravery I witnessed in the men I served with. Then I wonder why we risked so much for that person’s freedom.

I remember that it’s always incumbent upon the brave to protect the fearful, for a few to sacrifice for the many, but it doesn’t feel good when I compare the fear of driving through a minefield, getting shot at by snipers or having mortars explode around me to someone’s fear of simply asking me what that was like.

Lippmeier: The number one question people shouldn’t ask is, “Have you ever killed anyone?” That is by far the question I ‘ve been asked the most, and it’s definitely a loaded question and a very personal one, as well.

Besides that, most vets will let you know if they don’t want to answer a certain question, or they may shut down if a question strikes a nerve. Again, just respect that and move on. I’m sure there are questions that would make anyone uncomfortable, so just use your best judgment and treat vets with the same respect you would treat any person you just met.

Q: Are there any things you wish people knew about the military or veterans?

Nash: Not every service member experiences combat. Most don’t. It’s important to not discount their sacrifice in the time they spend away from their loved ones and the relative hazards to their job. Also, when it comes to injuries, you must understand that paralysis and amputations are dramatic, but many injuries are unseen. A lot of folks look at me and say things like, “Well, it looks like you are doing just fine.” To which I think, yeah, it’s just my brain and spine that were damaged. No big deal. But I don’t say that.

Lippmeier: The biggest thing that I wish people knew is that everyone’s military experience will vary. Just because someone was in the military doesn’t mean they were in combat. The majority of veterans don’t see combat, but just because a vet wasn’t in combat doesn’t make their service less honorable. Without vets that didn’t see combat, the combat guys wouldn’t be able to do their jobs.

Another thing is that not all injuries are visible. You can spot guys who are missing limbs or using wheelchairs or other devices, but the majority of vets who are injured have “invisible wounds.” Just because I have 10 fingers and 10 toes doesn’t mean I don’t have five herniated discs, scar tissue in my brain, severe post-traumatic stress disorder, and a laundry list of other injuries. So just realize there can be a plethora of things going on with someone even though he or she looks ok.

Q: Any other tips for how civilians can communicate better with veterans?

Lippmeier: Treat veterans like normal people, but realize they’ve had a lot of different experiences than non-vets. Just be patient, and veterans will usually open up after some time. It’s sometimes hard for veterans to let someone in their life, because they may have seen or had someone close to them be violently torn from their life.

Nash: Know that if you ask these questions, the answers may make you uncomfortable. Try to compare your discomfort with the experience of the person you are speaking to, and hopefully it will give you the guts the hang in there and have the conversation. Let veterans know their sacrifices were worth the cost.

I salute our veterans

I salute America’s military men and women, including Captain Nash and Staff Sergeant Lippmeier, and am forever grateful to those who trust me enough to share their stories. We must never forget their service and their sacrifices. (Click here to hear Captain Nash, in his own words, talk about everything from hunting to his experiences as an officer to being awarded the Purple Heart.)

Some veterans will tell you that Veterans’ Day is the time to member those who survived, while Memorial Day is to honor those who have died. That’s true, yet Memorial Day to me means a time to honor all our military personnel, including those who have passed away, veterans who are still with us and those serving on active duty.

A respect for all veterans was instilled in me from childhood as my parents took me each May to the Lake City Cemetery for the Memorial Day service. The roll call of the deceased is one of the most poignant parts of the service. As I listen for the name Henry C. Nicholson, an ancestor of mine who fought in the Civil War, I also glance around the crowd and see the veterans who are still with us. These men and women are my friends and neighbors who came back to Iowa to farm, work hard, raise a family and give back to their community. These are the everyday people who make America work.

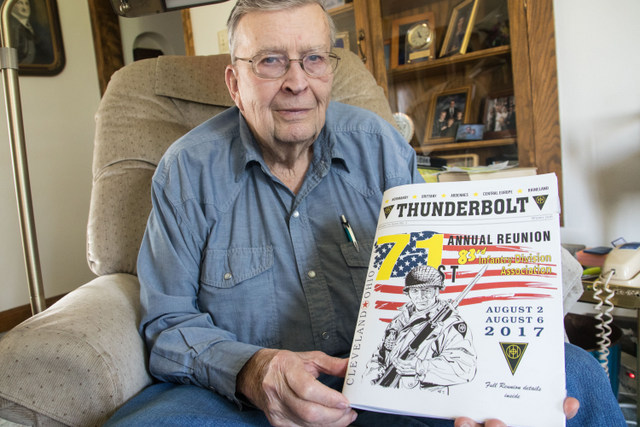

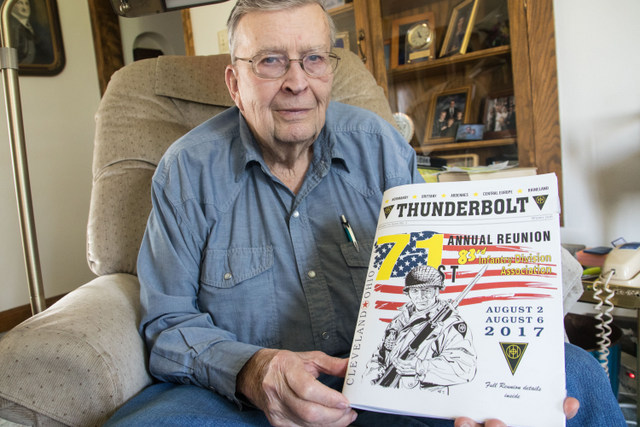

Harold Geisinger, 91, of Storm Lake, Iowa served in Europe in the U.S. Army during World War 2. This retired farmer continues to help on his family’s farm north of Storm Lake.

“Thank God it’s over”

Most of these veterans are humble, unassuming people, like Harold Geisinger of Storm Lake. I was honored to sit down with this World War 2 veteran this May. What started as as interview about his family’s Buena Vista County Century Farm turned into an unforgettable conversation about his service in the U.S. Army in the waning days of World War 2. Here’s a sample of his story, which I originally wrote for Farm News:

While V-E Day (Victory in Europe) was proclaimed “the celebration heard ‘round the world,” it was only a temporary reprieve for Harold Geisinger. This 19-year-old Iowa farm boy from Storm Lake was on his way to Le Havre, France, with the U.S. Army when Germany surrendered unconditionally to the Allies on May 7, 1945.

After a low-key celebration, Geisinger and his fellow soldiers boarded a box car in France bound for Hanover, Germany. Geisinger then joined a convoy in Bavaria, the section of Germany where American troops were guarding railroads, train depots, irrigation sites and more.

While the war was over in Europe, fighting continued on the other side of the globe. In the summer of 1945, there was talk that Geisinger and his fellow soldiers would likely be on board the next U.S. military ship bound for the Pacific Theater. Everything changed, however, when Japan surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945, following President Harry S. Truman’s orders to drop two atomic bombs on Japan in August 1945.

“When we got the word that Japan quit, we didn’t celebrate,” said Geisinger, 91, who still gets tears in his eyes when he thinks back to those days nearly 72 years ago. “We simply sat down and said, ‘Thank God it’s over.’”

Read off of Harold’s remarkable story here.

Want more?

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by and listening to these stories. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you want more Iowa stories, history and recipes, as well as tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Let’s stay in touch.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

“Thank God It’s Over:” Iowa Veteran Recalls the Final Days of World War 2

While V-E Day (Victory in Europe) was proclaimed “the celebration heard ‘round the world,” it was only a temporary reprieve for Harold Geisinger. This 19-year-old Iowa farm boy from Storm Lake was on his way to Le Havre, France, with the U.S. Army when Germany surrendered unconditionally to the Allies on May 7, 1945.

After a low-key celebration, Geisinger and his fellow soldiers boarded a box car in France bound for Hanover, Germany. Geisinger then joined a convoy in Bavaria, the section of Germany where American troops were guarding railroads, train depots, irrigation sites and more.

While the war was over in Europe, fighting continued on the other side of the globe. In the summer of 1945, there was talk that Geisinger and his fellow soldiers would likely be on board the next U.S. military ship bound for the Pacific Theater. Everything changed, however, when Japan surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945, following President Harry S. Truman’s orders to drop two atomic bombs on Japan in August 1945.

“When we got the word that Japan quit, we didn’t celebrate,” said Geisinger, 91, who still gets tears in his eyes when he thinks back to those days nearly 72 years ago. “We simply sat down and said, ‘Thank God it’s over.’”

After graduating from Storm Lake High School in 1944, Harold Geisinger was drafted into the U.S. Army on Aug. 2, 1944. “Back then, we all wanted to serve,” he said.

Battle of the Bulge put Geisinger on the fast track

As a World War 2 veteran, Geisinger is becoming a rare breed. Only 620,000 of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II were alive in 2016, according to U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs statistics.

Like many members of the Greatest Generation, Geisinger’s life would never be the same after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. “I was walking up the steps of our house and the radio was on,” said Geisinger, who stills lives in this house on the north edge of Storm Lake. “That’s when I heard the news about Pearl Harbor.”

After graduating from Storm Lake High School in 1944, Geisinger was drafted into the U.S. Army on Aug. 2, 1944. “Back then, we all wanted to serve,” he said.

Following 17 weeks of basic training in Arkansas, things moved quickly for Geisinger. “As my basic training was ending, the Battle of the Bulge was beginning, so the Army fast tracked us,” said Geisinger, who left on Christmas Day 1944 for Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts. This U.S. Army camp functioned as a departure area for thousands of U.S. soldiers during World War 2.

In mid-December 1944, Germany had launched its last major offensive and intended to split the Allied armies. This surprise blitzkrieg in northwest Europe, which became known as the Battle of the Bulge, did not turn the tide of the war in Adolph Hitler’s favor but did result in American and civilian casualties.

The Battle of the Bulge was still raging when Geisinger shipped out for Europe on January 2, 1945. “I was on my two-week ‘ocean cruise,’” said Geisinger, who had turned 19 just a few days earlier on Christmas Eve.

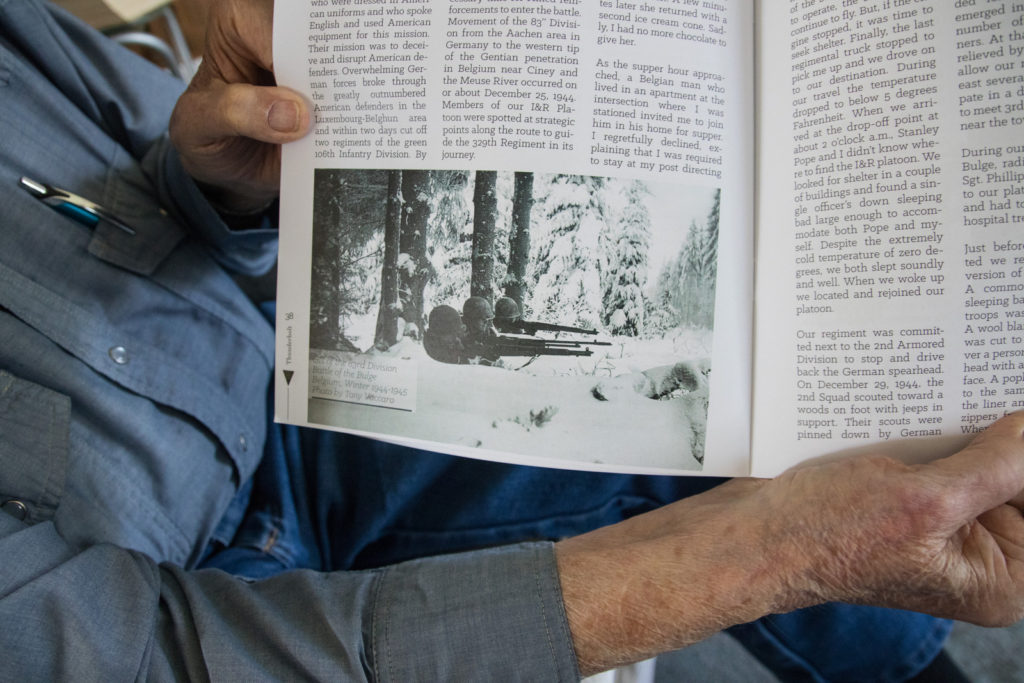

When Geisinger and his fellow soldiers with the Army’s 83rd Infantry Division, Company I, arrived at Le Havre, France, they were transferred to railroad box cars bound for Givet, a small community in the north of France, near the Belgian border. “These box cars were called ’40 by 8s,’ meaning they could hold 40 men or 8 horses,” said Geisinger, who recalled that it was close to a month after he left America before he had the chance to take a real shower—not just a saltwater shower on the ship.

The Battle of the Bulge was still raging when Harold Geisinger shipped out for Europe on January 2, 1945. Geisinger and his division spent most of their time training in the Hürtgen Forest, located along the border between Belgium and Germany. “Our division was preparing to push across Germany,” Geisinger said.

Much worse than the shower situation, however, were the frigid January temperatures and lack of adequate overshoes during the box car ride. “I froze my feet,” Geisinger recalled.

After reaching their destination, Geisinger and his division spent most of their time training in the Hürtgen Forest, located along the border between Belgium and Germany. “Our division was preparing to push across Germany,” Geisinger said.

In the meantime, however, Geisinger was waging his own battle with a cough that wouldn’t go away. The coughing became severe that he couldn’t eat. On Feb. 14, 1945, he had to go on sick call and was diagnosed with viral pneumonia. Geisinger returned to France and was transferred to a hospital in southern England at Newton Abbot. “I was there two months with no medicine,” said Geisinger, who eventually recovered and returned to active duty.

In early May 1945, Geisinger was crossing the English Channel in a ship bound for Le Havre, France, when he heard the news that Germany had surrendered. Although Hitler and the Nazis had been defeated, Geisinger knew he wouldn’t be returning home to northwest Iowa anytime soon. After boarding another box car, Geisinger headed to Bavaria to rejoin Company I and the men he had served with before.

Everyone wondered if they’d be called to fight the war in Japan. “Had we shipped out, some said we would have left from Marseille in southern France and sailed around Cape Horn and onto Japan,” Geisinger said. “When I heard that Japan surrendered, I kept thinking, ‘Someday we’ll get to go home.’”

Transitioning from solider to farmer

That day wouldn’t come for months, however. Geisinger remained in Europe and remembers pulling guard duty along the Danube River. He crossed the river with a buddy one night to meet Russian soldiers on the other side.

“We drank a little beer with a Russian sergeant and tried to communicate using hand signals and the little bit of German we and the Russian had picked up,” Geisinger said. “The one thing the Russian sergeant wanted was American uniforms. He wanted all the American uniforms he could get.”

Geisinger couldn’t access any uniforms other than the one he was wearing. He had no idea why the sergeant wanted American uniforms, although he later suspected an ulterior motive. “I assumed it was for infiltration,” said Geisinger, whose distrust of the Russian sergeant proved accurate as the Cold War heated up.

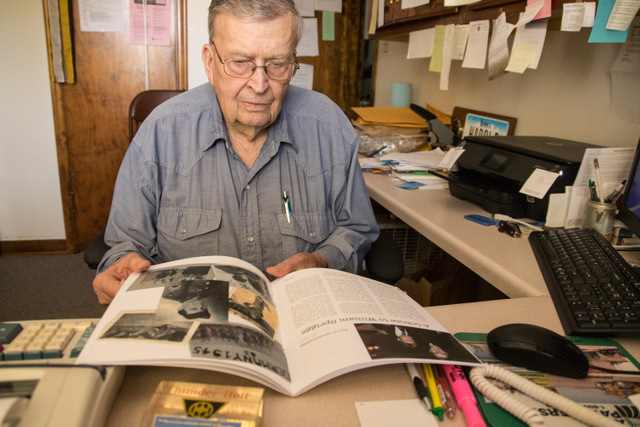

As he sits in his home office, Harold Geisinger looks through pieces of the past, including World War 2 history books.

By the time Geisinger was honorably discharged from the Army, he had achieved the rank of corporal. He looked forward to returning to Storm Lake to farm and finally reached home in July 1946. By then, agriculture had entered a new era as the transition to mechanical horsepower from traditional horsepower became complete. New equipment like combines also became more common in row-crop production.

Geisinger started farming with his father, L.J. Geisinger, on the Washington Township farm north of Storm Lake that had been in their family since 1915. Geisinger also used the G.I. Bill to earn his pilot’s license and enjoyed flying for many years.

Geisinger and his wife, Laura May, a Storm Lake High School classmate, raised their three children on the farm, along with corn, soybeans, hay, cattle and hogs. Farming still interests Geisinger, who helps run the field cultivator in the spring and helps combine in the fall. “I even planted some beans this spring,” said Geisinger, who is proud of the rich heritage of his family’s Century Farm in Buena Vista County.

For decades, Geisinger served as a rifleman in the color guard unit in Alta (VFW Post 6172). While he has retired from these duties, his memories of World War 2 remain vivid, and he’s proud he was able to serve his country.

“My military experiences gave me more of global view of the world,” Geisinger said. “Even though a lot has changed since World War 2 and America has its deficiencies, I don’t know of a better place to call home.”

Harold Geisinger’s memories of World War 2 remain vivid, and he’s proud he was able to serve his country.

It was truly an honor to meet Harold Geisinger in May 2017 and interview him at his home and at his family’s farm north of Storm Lake, Iowa. He is a living legacy of America’s Greatest Generation. I’m forever grateful that Harold and hundreds of thousands of others like him were willing to serve. I’m also thankful he was willing to share his stories with me so I can share them with you. (I originally wrote this article for the Memorial Day 2017 of Farm News.)

Want more Iowa culture and history?

I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you want more Iowa stories, history and recipes, as well as tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Let’s stay in touch.

Also, if you enjoyed Harold’s military story, be sure to check out my Memorial Day 2017 post on “How to Thank Veterans for Their Service.” I interviewed two recently-retired U.S. Marines from the Wounded Warrior Battalion, and their insights are invaluable.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

Harold Geisinger served with the U.S. Army’s 83rd Infantry Division, Company I,

Get Your Grill On: How to Build a Better Burger

Love the thrill of the grill? I sure do, especially when I’m crafting a thick, juicy burger I can sink my teeth into. While we talk a lot about burgers during May Beef Month, how much do you really know about this American icon?

The classic hamburger we know and love today is very much an American invention. Stemming from German culinary roots, the burger-on-a-bun phenomenon gained widespread fame at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

Disaster struck two years later, however, when Upton Sinclair’s novel “The Jungle” (remember the book’s lurid details from high school literature class?) detailed the unsavory side of the American meatpacking industry. Ground beef became a prime suspect, since it could easily be adulterated with questionable additives.

The hamburger might have faded away as a long-forgotten fad were it not for Edgar Ingram and Walter Anderson. When they opened their first White Castle restaurant in Kansas in 1921, White Castle countered the hamburger’s unsavory reputation by becoming bastions of cleanliness, health and hygiene. This paved the way for national hamburger chains founded in the post-World War II boom years, including McDonald’s.

Best burgers, Iowa style

Iowa has made its own distinctive contributions to America’s burger history. Consider the wildly popular Iowa’s Best Burger contest, sponsored by the Iowa Cattlemen’s Association (ICA) and the Iowa Beef Industry Council (IBIC). Iowans submitted more than 9,200 nominations for this year’s contest. Nearly 500 Iowa restaurants were represented in 2017 in the total nominations, setting a new record for the contest.

As a former judge of Iowa’s Best Burger contest, I can tell you how tough it is to pick a winner. Iowans know how to make bodacious burgers, a story I made sure to include in my “Culinary History of Iowa” book.

Size matters when it comes to the Gunderburger at the Irish Shanti, which made the 2017 Top 10 list. The famous Gunderburger started in the late 1970s to put the tiny northeast Iowa community of Gunder on the map. The first Gunderburgers were a smaller version of the one served today. As the Gunderburger started growing in size in the 1990s, its notoriety also grew.

Another 2017 Top 10 Best Burger in Iowa contender is the Ankeny Diner, which offers Maytag Burgers, featuring Iowa’s famous Maytag blue cheese, sautéed onion and Monterey jack cheese. Don’t care for blue cheese? Maybe you’d prefer the Rarebit Burger, served open-faced and topped with spicy Cheddar cheese sauce.

Rarebits were legendary at the iconic Younkers Tea Room in downtown Des Moines for decades. An Iowa-style rarebit burger elevates the traditional Welsh rarebit, which incorporates leftover bits of cheese and the end-of-the-loaf slices of stale bread for a quick supper.

Speaking of Des Moines, the historic East Village is the home of the incomparable Zombie Burger. A previous Top 10 Best Burger in Iowa contender, Zombie Burger serves “gore-met” creations made from the shop’s own custom three-cut beef burger blend. With locations in downtown Des Moines, Ankeny, West Des Moines and the Iowa City area, Zombie Burger is distinguished by classics from the Undead Elvis (a burger paired with peanut butter, fried bananas, bacon, American cheese and mayo) to the Walking Ched (a burger featuring bacon, Cheddar cheese, caramelized onions and mayo on a deep-fried macaroni-and-cheese bun).

Hungry yet?

If all this inspiration has you craving top-quality, Iowa beef, here are my top tips to make your best burgers ever:

• Choose fresh 80/20 ground beef, which provides enough fat to keep your burgers juicy and flavorful.

• Worcestershire sauce adds a whole new depth of flavor to burgers. Add in a healthy dollop and mix it into the meat before forming the patties.

• Use your thumb to create a dimple or well in the center of each patty on the bottom. This helps ensure that the burgers cook evenly. Don’t worry—the indentation will hardly be noticeable by the time the burgers are ready.

• Cook your burgers over medium heat.

• As the patties cook, sprinkle them liberally on both sides with a mixture of salt, fresh-ground pepper, Lawry’s seasoning salt, garlic powder and onion powder.

• Avoid using your spatula to press down on your burgers while cooking. Don’t let all those flavorful juices escape.

• Allow your burgers to rest for a few minutes before serving. This will ensure that the juices redistribute into the meat. Enjoy!

Have any favorite burger recipes or cooking tips? I’d love to hear them. Now go get your grill on!

Hungry for more?

Want more burger inspiration? Check out my blog post on the Lake City Drive-In, where owner Larry Irwin is not only a beef booster, but someone who sees burgers as the perfect palette for culinary creativity with his Burger of the Month flavors. (Don’t miss my recipe for Meatloaf Burgers!)

Larry Irwin shows off some tasty burgers from the Lake City Drive-In.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, Larry is kind enough to carry my books at the Lake City Drive-In. Not close to Lake City? I invite you to visit my online store, where you can purchase my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

One more thing–check out more of my blog posts if you want more Iowa stories, history and recipes, as well as tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Let’s stay in touch!

This originally appeared as one of my weekly columns in Farm News.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

Iowa Beef Booster: Larry Irwin Takes a New Twist on Burgers

Make no mistake, the humble hamburger still reigns supreme from backyard barbecues to fast-food drive-ins across Iowa. But this Iowa icon also provides the perfect palette for culinary creativity when my friend Larry Irwin showcases his Burger of the Month flavors in my hometown of Lake City.

“I’m not doing anything fancy,” said Irwin, who has run the Lake City Drive-In since 2012. “I just like cooking down-home, comfort food.”

While it’s hard to beat a classic bacon cheeseburger, which remains one of the Lake City Drive-In’s top sellers, customers also love the monthly burger specials. Favorites include the Taco Burger (spiced with taco seasoning and chipotle and topped with nacho-cheese flavored chips), Darcy’s Meatloaf Burger, the Swiss Mushroom Burger, and the Ranch Burger (enhanced with homemade ranch dressing, pepper jack cheese and bacon).

“Burgers of all types are always our top sellers,” said Irwin, who serves more than 50 burgers a day, on average. “It’s fun to experiment with new flavors and feature them as the Burger of the Month.”

Top tips for unbeatable burgers

Interestingly, this adventurous spirit in the kitchen isn’t second nature for Irwin, who spent more than 30 years of his career in finance and banking. “I never did much cooking at home,” said Irwin, who grew up on a cattle and grain farm between Lohrville and Rockwell City. “I certainly never thought I’d run a restaurant.”

Irwin has found that offering new men

Larry Irwin shows off some tasty burgers from the Lake City Drive-In.

u items is one of the secrets to keep people coming back to the Lake City Drive-In. Inspiration for the Burger of the Month comes from a variety of sources.

“Sometimes our customers suggest ideas,” Irwin said. “A lot of the Burger of the Month ideas come from my son, Chris, who is an agronomist in northeast Iowa. He travels a lot for his job and tells me about burger flavors he discovers in various cafes.”

While unique flavors are part of the fun, a great burger starts with the basics, said Irwin, who shares the following tips:

• Select an 80/20 ground beef for the best flavor. Irwin always uses fresh beef, never frozen patties, to make his 1/3 pound burgers.

• Preheat the grill before you place the hamburger patties on the grill.

• Cook the hamburger patties over medium heat. If the temperature is too high, it’s easy to burn the outside of the burger and leave the inside undercooked, said Irwin, who cooks his burgers for about five minutes on each side.

• Season the patties on the grill. Irwin sprinkles a mix of garlic powder, onion powder, Lawry’s seasoning salt, table salt, white sugar and black pepper on both sides of each hamburger patty as the meat cooks.

• Don’t forget to butter and toast the bun before serving the burger.

Time-saving systems in the kitchen are also invaluable. Since the Lake City Drive-In is located on Main Street across from South Central Calhoun High School, things can get hectic when hungry crowds stop by, especially during volleyball tournaments and home football games. Irwin plans ahead on these days and cooks each hamburger patty for two minutes per side before placing the partially-cooked patties in a warm slow cooker. When the crowds arrive, it only takes a couple more minutes of grilling time before the burgers are ready.

This strategy also pays off during planting and harvest, when the drive through becomes one of the busiest places at the Lake City Drive-In. “You can always tell when an order is going out to farmers, because there are at least five or six cheeseburgers in there,” said Irwin, who farmed at one point in his career.

Keeping things simple while adding a little variety is the key to a great burger, Irwin added. “I love the flavor of beef. If I could only have one meat for the rest of my life, I’d choose hamburger, because I can make anything out of it.”

Hungry for more? Check out my blog post and Farm News column “Get Your Grill On: How to Build a Better Burger.”

Darcy’s Meatloaf Burger

Darcy’s Meatloaf Burgers

Larry Irwin will be featuring these Meatloaf Burgers, made from my recipe, as the Burger of the Month in June 2017.

2 pounds ground beef

1 1 / 2 to 2 cups herb-seasoned stuffing mix (experiment to find what amount helps the burger patties stick together the best)

1 onion, chopped

1 teaspoon seasoning salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly-ground pepper

1 teaspoon garlic powder

2 large eggs, lightly beaten

1 /4 cup milk

2 tablespoons barbecue sauce

1 / 4 cup ketchup

2 tablespoons brown sugar

1 teaspoon dry mustard

Combine ground beef, stuffing mix, onion, salt, pepper and garlic powder. In a separate bowl, beat eggs, milk, and barbecue sauce. Combine barbecue sauce mixture with meat mixture.

In a separate bowl, combine ketchup, brown sugar and dry mustard. This mixture can either be spread as a glaze while the burgers are cooking on the grill, or the glaze can be mixed into the burger patty mixture before the burgers are grilled.

Shape beef mixture into patties. Grill over medium heat to desired doneness. If using the ketchup mixture as a glaze, spread over the top of each burger during the final minutes of cooking on the grill.

Ranch Dressing

While this makes restaurant-sized quantities, scale down the recipe for home use.

1 gallon regular mayonnaise

1 / 2 gallon buttermilk

2 packages (3.2 ounces each) powdered ranch dressing mix

Combine all ingredients and stir with an electric mixer. Refrigerate.

Boom Boom Sauce

This spicy sauce has a kick and tastes great on burgers and salads.

4 cups Thousand Island dressing

3 / 4 cup buffalo hot sauce

1 / 4 cup red pepper flakes

Combine dressing, buffalo sauce and red pepper flakes; refrigerate.

Sloppy Joes

1 pound hamburger

1 can chicken gumbo soup

Ketchup and mustard, to taste

Brown sugar, to taste

Salt and pepper, to taste

Brown the hamburger; drain. Add soup and season with ketchup, mustard, brown sugar, salt and pepper until the desired flavor is achieved.

This story first ran on Farm News, May 2017.

Want more Iowa culture and history?

Read more of my blog posts if you want more Iowa stories, history and recipes, as well as tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, Larry is kind enough to carry my books at the Lake City Drive-In. You can also check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

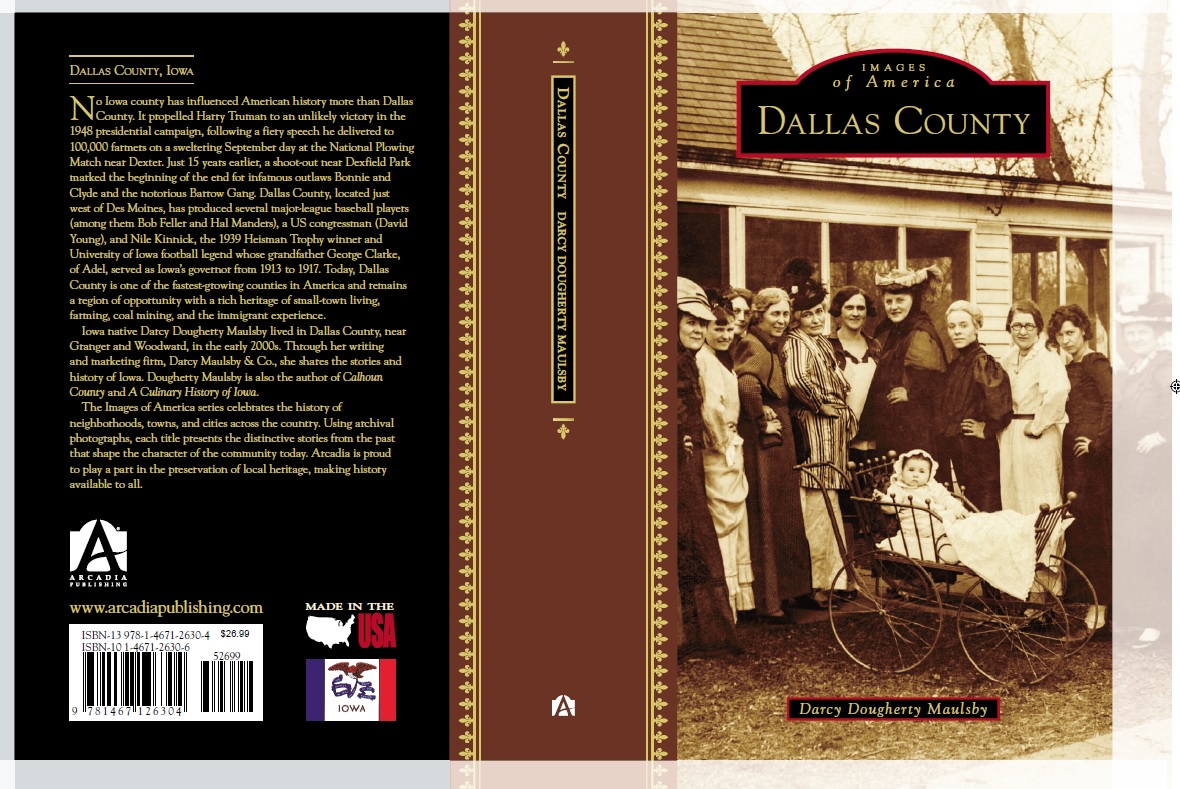

Coming Soon–“Dallas County,” a New Iowa History Book!

No Iowa county has influenced American history more than Dallas County. It propelled Harry Truman to an unlikely victory in the 1948 presidential campaign, following a fiery speech he delivered to 100,000 farmers on a sweltering September day at the National Plowing Match near Dexter. Just 15 years earlier, a shoot-out near Dexfield Park marked the beginning of the end for infamous outlaws Bonnie and Clyde and the notorious Barrow gang.

Dallas County, located just west of Des Moines, is a study in contrasts, from its key role on the Underground Railroad in the 1850s to the revival of the KKK in the 1920s. Dallas County has also produced several Major League Baseball players (including cousins Bob Feller and Hal Manders), a US congressman (David Young), and Nile Kinnick, the 1939 Heisman Trophy winner and University of Iowa football legend whose grandfather, George Clarke of Adel, served as Iowa’s governor from 1913 to 1917.

I’m very excited to announce that “Dallas County,” my third Iowa history book, will be released by Arcadia Publishing on Sept. 4, 2017! This will also be one of the publisher’s first books to be available in a hard cover version for $26.99. Want to know the story behind the cover? These dynamic ladies of the Van Meter Matrons Club (founded in 1909) socialized while improving their knowledge of Iowa heritage and current events. When the group celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1959-1960, historian Hazel Lauterbach said the group “helped me be a better homemaker, citizen, and community member and has taught me the true meaning of teamwork.”

Discover the fascinating stories of Dallas County, which is one of the fastest-growing counties in America and remains a region of opportunity with a rich heritage of small-town living, farming, coal mining, and the immigrant experience.

More details coming soon!

Want more Iowa culture and history?

Read more of my blog posts if you want more Iowa stories, history and recipes, as well as tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

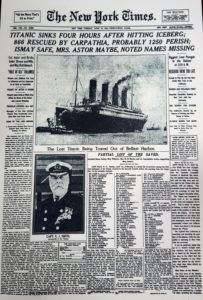

Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic

I perished on the Titanic, yet I’ve lived to tell the forgotten stories of Iowa’s ties to one of the most famous luxury liners in history. It all started when I attended the Johnson County H istorical Society’s “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic” in April 2, 2017, and my boarding pass said I was third-class passenger Frances Lefebvre, 40, of Lievin, France.

istorical Society’s “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic” in April 2, 2017, and my boarding pass said I was third-class passenger Frances Lefebvre, 40, of Lievin, France.

As Lefebvre, my four youngest children and I were traveling to Mystic, Iowa, to join my husband, Franck, and our for older children who had moved to Iowa a year prior. I died, along with my four youngest kids, during the sinking of Titanic in the early-morning hours of April 15, 1912.

I was not alone. Of the approximately 2,207 passengers who boarded the Titanic, only an estimated 705 survived. Like Frances Lefebvre, a number of Titanic’s passengers had ties to Iowa. Here are their stories.

Titanic survivor, Orphan Train rider kept low profile in Council Bluffs

One of Titanic’s last living survivors lived in Council Bluffs for decades and rarely spoke of the maritime tragedy or her connection to the Orphan Train Movement.

Helen Delaney’s remarkable story began when she was thrown overboard as Titanic sank. Someone caught the 4-year-old, and she survived the night, although her parents perished. While the family had boarded the ship in England, the names of Delaney’s birth parents are unknown, and Delaney’s didn’t know her exact birth date, according to a 2012 news report in the Council Bluffs Daily Nonpareil.

With the other Titanic survivors, Delaney arrived in New York on April 18, 1912, where she was placed in an orphanage. James P. Delaney, a Council Bluffs locomotive engineer for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Rail Company (now BNSF), and his wife adopted the girl after she arrived in Council Bluffs via an orphan train sometime in the mid to late 1910s.

Orphan trains brought thousands of children to Iowa and beyond

Orphan trains brought thousands of children to Iowa and beyond

Children on these orphan trains ranged in age from about six to 18, and they shared a common grim existence. There was little hope of a successful future for these kids if they stayed in the streets, slums and orphanages of New York City.

Their numbers were staggering. An estimated 30,000 children were homeless in New York City as early as the 1850s. The plight of these abandoned, neglected children commanded the attention of a young minister named Charles Loring Brace. He believed that by removing youngsters from the poverty of the city and placing them with Christian farm families, these children could have a chance of escaping a lifetime of suffering.

Brace, who founded the Children’s Aid Society, proposed that these children be sent by train to live and work on farms out west. They would be placed in homes for free but they wouldn’t be indentured.

Children like Helen Delaney boarded westbound trains in groups of up to 40, accompanied by two agents from the Children’s Aid Society. Advertisements appeared in local newspapers along the route in advance of each orphan train’s arrival. When the trains stopped, the children were paraded in front of the crowd and took turns giving their names, singing a song or “saying a piece,” according to “Lost Children: Riders on the Orphan Train,” an article that appeared in HUMANITIES magazine in November/December 2007.

Although the strong demand for the orphans was often motivated by a need for labor, the Children’s Aid Society took pains to ensure the children were well cared for. Families applying to take children had to be endorsed by a committee of local business owners, doctors and other respected community members. Representatives from the society would visit each family once a year to check on conditions, and children were expected to write letters back to the society twice a year, noted the “Lost Children” article.

The Orphan Train Movement, which lasted from 1853 to 1929, placed nearly a quarter of a million children in new homes across the country. This ambitious, unusual social experiment is now recognized as the beginning of the foster care concept in the United States. While some of the children struggled in their newfound surroundings, many others like Helen Delaney went on to lead successful, normal lives as they worked towards the American dream.

Delaney attended school in Council Bluffs, including Mount Loretto Catholic High School. She remained in Council Bluffs, never married and never had children. She lived in anonymity in an apartment at Regal Towers on South Sixth Street, according to the Council Bluffs Nonpareil.

For much of her adult life, Delaney worked as a sales clerk at the Kresge’s five-and-dime store. Only a few people in town knew that this petite, shy, nice clerk had survived Titanic. “She rarely talked about her Titanic legacy,” Dick Warner of the Historical Society of Pottawattamie County told the Council Bluffs Nonpareil in 2012. “Most people who knew her weren’t even aware of it.”

Delaney died on January 26, 1982, at age 74 and was buried at St. Joseph Cemetery off McPherson Avenue in Council Bluffs. She was the only known passenger on Titanic to live in Council Bluffs.

Picture from the book “Not My Time to Die” by Lilly Setterdahl

“Life no longer has any value for me”

Like Delaney, many of Titanic’s survivors and victims were immigrants headed to America to begin a new life. In other cases, the travelers were only planning to visit before returning to Europe. Such was the story of second-class passenger Dagmar Lustig Bryhl, 20, who looked forward to attending a wedding in Red Oak, Iowa, and visiting her uncle Oscar Lustig in Rockford, Illinois, before returning to Sweden.

Author Lilly Setterdahl of East Moline, Illinois, has captured the often heartbreaking—and sometimes heroic—stories of Bryhl and the 122 other Swedes on board Titanic in her fascinating 2012 book, Not My Time to Die. I listened for any tidbits connected to Iowa as Setterdahl related many of these stories during the “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic” in Iowa City.

Consider the letter Bryhl wrote to her uncle while she recuperated in New York following the Titanic disaster (as documented in Not My Time to Die, page 119). Bryhl became so distraught that she wished she had been permitted to die on Titanic with her fiancé, Ingvar Enander, and brother, Kurt.

Dear Uncle,

Titanic has gone down. I don’t know whether my fiancé and my brother Kurt are saved. Evidently, they are not, for most of the men went under. I am at a hospital but am not sick, although very feeble. I have lost everything. I have no clothes, and so cannot get up, so must lie in bed for present.

I would have been glad if I had been permitted to die, because life no longer has any value for me since I lost my beloved. I feel myself so dreadfully alone in this land. These people are certainly good, but nevertheless do not understand me.”

Bryhl asked her uncle to come find her, which he did. Bryhl required bed rest after the long, tiresome journey to Rockford, and she refused to talk to reporters. Her uncle related bits and pieces of her story to local newspapers.

“I was in my berth when the Titanic hit the berg. I noticed the jar and soon I heard Ingvar [her fiancé] knocking on the door of my cabin.“Get up, Dagmar,” he said. “The ship has hit something.” I put on a skirt and coat as quickly as possible and hurried up to the deck. But the officers said, “Go back, there is no danger, you go to your cabins.”

Bryhl returned to her berth and went back to bed. Soon there was more knocking on her door.

“Get up, Dagmar, we are in danger!” Ingvar yelled. “I don’t care what the ship’s officers say. The boat is sinking.”

After pulling on her skirt and coat and running from her berth, Bryhl heard awful screaming and yelling. Women and children were being loaded into lifeboats. Men and women were kissing each other farewell. Ingvar and Kurt led Bryhl to a lifeboat, and Ingvar lifted his fiancé into the boat. She seized his hands and wouldn’t let go. “Come with me!” Bryhl screamed as loud as she could, still holding Ingvar’s hands tight. There was room in the lifeboat, which was only half full. Suddenly an officer ran forward and clubbed back Ingvar.

“This officer tore our hands apart, and the lifeboat was let down. As it went down, I looked up. There, leaning over the rail stood Kurt and Ingvar side by side. I screamed to them again, but it was no use. They waved their hands and smiled. That was the last glimpse I had of them.”

As the men in the lifeboat rowed the boat away from Titanic, the passengers shivered in the frigid night air as they watched the great ship sink.

“Then more dreadful screams,” said Bryhl, who recalled that the sea was so still it was clear as a mirror beneath the cloudless sky. “The water filled with crying people. Some of them climbed in our boat and so saved their lives.”

The small group of survivors huddled in the lifeboat until 6 a.m. on Monday, April 15, when the Carpathia arrived. Hours in the freezing air without adequate clothing to protect against the stinging cold numbed Bryhl’s body.

According to her uncle, Bryhl declared repeatedly between hysterical sobs that she never would have allowed her brother and fiancé to put her in the lifeboat if she thought the two men would be lost. She said she would rather have died with them when the great ship settled into the depths than to live with the memory of all that took place.

Bryhl returned home to Sweden in May 1912 after only a short time in Rockford. She later married a teacher named Eric Holmberg. She died in August 1969, Setterdahl noted.

“Not my time to die”

“Not my time to die”

During “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic,” Setterdahl (a native Swede herself) also detailed the life of 22-year-old Anna Nysten, the woman whose story provided the title for Setterdahl’s book.

Nysten had planned to leave Sweden in the summer of 1912 to visit her sister Klara in Passaic, New Jersey. However, some of Nysten’s friends who were headed to America that spring persuaded her to go with them. Nysten traveled with the Andersson family from Kisa, Sweden, and the Danbom family from Stanton, Iowa. Nysten would be the lone survivor of the 11-member group.

“I can hardly describe how it happened,” Nysten wrote to her parents in the wake of the Titanic disaster. “There was terrible screaming and groaning, but you and I ought to thank God that I am alive. I managed to get into a lifeboat because I don’t think it was my time to die. I’m supposed to experience more of the world.”

Nysten offered more details of the disaster after Titanic struck the iceberg (as documented in Not My Time to Die, pages 167-169).

“There was a terrible jolt, so we nearly fell out of bed. But then they said it was not serious, so the passengers calmed down until the ship began to sink and the deck was full of people.”

After someone took Nysten’s lifebelt and she began crying, a sailor gave her his life jacket. While her traveling companions proclaimed they would all go down together with the ship, a sailor pushed Nysten into a lifeboat.

“Oh, how terrible it was when everything went dark,” said Nysten, who recalled that her lifeboat could have held 63 people but only had about 40 passengers when it was lowered into the sea. “When the ship went down we were not far away and were almost sucked under.”

Nysten and the others in the lifeboat heard an awful rumbling noise as the great ship sank. They sat in the lifeboat from 1:30 a.m. to 6:30 a.m., but “fortunately the sea was calm,” she recalled.

“You can imagine how happy we were to see the steamer Carpathia close in on us and we could come aboard. They were so good to us.”

The survivors were given blankets, coffee and brandy (“as much as we wanted,” Nysten noted).

“But there was still much groaning and crying because most of us had lost a dear relative,” Nysten recalled. “Many became hysterical.”

In New York, Nysten was taken to the Swedish Immigrant Home, where she received $25 from the Women’s Relief Committee. Nysten spent three years in New York with friends and intended to return to Sweden, but when the Lusitania was torpedoed in 1915, she changed her mind. She came to Boone, Iowa, and moved to Des Moines in 1916, where she married Arvid Gustafson in 1917. The couple had three sons and were members of the First Lutheran Church in Des Moines.

Nysten was one of the few Titanic survivors who married, had children and was not reluctant to talk about her Titanic experience, although it took several years after the sinking before she was willing to share many of those haunting memories, Setterdahl noted. In 1937 on the 25th anniversary of the tragedy, Nysten said in a newspaper interview that she no longer dreamed about the disaster.

Nysten passed away March 28, 1977, and is buried in Resthaven Cemetery in West Des Moines.

“The lifeboats were all gone”

Some Swedes on the Titanic like Gunnar Tenglin were returning to their adopted home in Iowa. Tenglin, 25, had grown up in Sweden and emigrated to America around 1903 at age 16. He settled in Burlington, Iowa. Until he learned to speak English he worked with crews cutting ice on the Mississippi River. He learned English while working at the Horace Patterson farm.

Tenglin returned to Sweden in 1908 where he married his wife, Anna. A year after the couple’s son, Gunnar, was born in Stockholm in 1911, Tenglin made plans to return to Burlington. He acquired a third-class ticket to travel on Titanic. Tenglin considered third class on Titanic equal to first class on most other steamers, noted Setterdahl, who documents his story in Not My Time to Die, pages 191-194.

Late in the evening of April 14, 1912, Tenglin and his traveling companion, August Wennerstrom (a fellow Swede who would also survive the sinking) had come back from a party on board Titanic. Tenglin had just taken off his shoes and was preparing for bed when he felt a thud. He put his jacket on but left his shoes in his bunk and his lifejacket under his pillow. He never returned for them.

When he came up on deck, all the lifeboats were gone. An officer on deck engaged Tenglin as an interpreter since the Swede knew English. Tenglin thought that saved him, as noted in a 2012 Burlington Hawk Eye article, because he was still on deck translating the officer’s commands to other Swedes. Otherwise, he may have been below deck when the ship when down.

Tenglin, a tall man of medium build with light blue eyes and brown hair, provided specific details of that unforgettable night to the Burlington Daily Gazette in 1912:

“It looked to us as if we were doomed to perish with the ship when a collapsible lifeboat was discovered. This boat would hold about 50 people, and we had considerable trouble getting it loose from its fastenings. The boat was on the second deck, and the ship settled the question of its launching, as the water suddenly came up over the deck and the boat floated.”

The terror was far from over, though.

“There must have been 150 people swimming around or clinging to the boat, and we feared it would collapse or sink,” Tenglin said. “We had no oars or anything else to handle the boat and were at the mercy of the waves, but the sea was calm.”

There was no way to sit down, so the boats passengers stood up in knee-deep, ice-cold water. Basic survival instincts dominated the horrific scene.

“Those on the edges pushed the frantic people in the water back to their fates, it being feared they would doom us all,” Tenglin said.

A big Swede named Johnson was kept busy throwing corpses overboard, Tenglin added, since the survivors wanted to make the boat as light as possible to increase its buoyancy.

Tenglin and other passengers in Collapsible A were rescued by the Carpathia. When the ship arrived in New York, the American Red Cross and the Swedish American Society took pictures of the surviving immigrants and printed the images as picture postcards. Tenglin sent one of those postcards to his mother in Sweden, mailing it from Burlington on April 29, 1912.

Tenglin lived the rest of his life in Iowa, where he was joined by his wife and son who arrived from Sweden in 1913. Tenglin worked various jobs during his career, from the railroad to the local utility plant that supplied Burlington with gas. Tenglin passed away in 1974 at age 86 in Burlington and is buried in Aspen Grove Cemetery.