Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic

I perished on the Titanic, yet I’ve lived to tell the forgotten stories of Iowa’s ties to one of the most famous luxury liners in history. It all started when I attended the Johnson County H istorical Society’s “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic” in April 2, 2017, and my boarding pass said I was third-class passenger Frances Lefebvre, 40, of Lievin, France.

istorical Society’s “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic” in April 2, 2017, and my boarding pass said I was third-class passenger Frances Lefebvre, 40, of Lievin, France.

As Lefebvre, my four youngest children and I were traveling to Mystic, Iowa, to join my husband, Franck, and our for older children who had moved to Iowa a year prior. I died, along with my four youngest kids, during the sinking of Titanic in the early-morning hours of April 15, 1912.

I was not alone. Of the approximately 2,207 passengers who boarded the Titanic, only an estimated 705 survived. Like Frances Lefebvre, a number of Titanic’s passengers had ties to Iowa. Here are their stories.

Titanic survivor, Orphan Train rider kept low profile in Council Bluffs

One of Titanic’s last living survivors lived in Council Bluffs for decades and rarely spoke of the maritime tragedy or her connection to the Orphan Train Movement.

Helen Delaney’s remarkable story began when she was thrown overboard as Titanic sank. Someone caught the 4-year-old, and she survived the night, although her parents perished. While the family had boarded the ship in England, the names of Delaney’s birth parents are unknown, and Delaney’s didn’t know her exact birth date, according to a 2012 news report in the Council Bluffs Daily Nonpareil.

With the other Titanic survivors, Delaney arrived in New York on April 18, 1912, where she was placed in an orphanage. James P. Delaney, a Council Bluffs locomotive engineer for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Rail Company (now BNSF), and his wife adopted the girl after she arrived in Council Bluffs via an orphan train sometime in the mid to late 1910s.

Orphan trains brought thousands of children to Iowa and beyond

Orphan trains brought thousands of children to Iowa and beyond

Children on these orphan trains ranged in age from about six to 18, and they shared a common grim existence. There was little hope of a successful future for these kids if they stayed in the streets, slums and orphanages of New York City.

Their numbers were staggering. An estimated 30,000 children were homeless in New York City as early as the 1850s. The plight of these abandoned, neglected children commanded the attention of a young minister named Charles Loring Brace. He believed that by removing youngsters from the poverty of the city and placing them with Christian farm families, these children could have a chance of escaping a lifetime of suffering.

Brace, who founded the Children’s Aid Society, proposed that these children be sent by train to live and work on farms out west. They would be placed in homes for free but they wouldn’t be indentured.

Children like Helen Delaney boarded westbound trains in groups of up to 40, accompanied by two agents from the Children’s Aid Society. Advertisements appeared in local newspapers along the route in advance of each orphan train’s arrival. When the trains stopped, the children were paraded in front of the crowd and took turns giving their names, singing a song or “saying a piece,” according to “Lost Children: Riders on the Orphan Train,” an article that appeared in HUMANITIES magazine in November/December 2007.

Although the strong demand for the orphans was often motivated by a need for labor, the Children’s Aid Society took pains to ensure the children were well cared for. Families applying to take children had to be endorsed by a committee of local business owners, doctors and other respected community members. Representatives from the society would visit each family once a year to check on conditions, and children were expected to write letters back to the society twice a year, noted the “Lost Children” article.

The Orphan Train Movement, which lasted from 1853 to 1929, placed nearly a quarter of a million children in new homes across the country. This ambitious, unusual social experiment is now recognized as the beginning of the foster care concept in the United States. While some of the children struggled in their newfound surroundings, many others like Helen Delaney went on to lead successful, normal lives as they worked towards the American dream.

Delaney attended school in Council Bluffs, including Mount Loretto Catholic High School. She remained in Council Bluffs, never married and never had children. She lived in anonymity in an apartment at Regal Towers on South Sixth Street, according to the Council Bluffs Nonpareil.

For much of her adult life, Delaney worked as a sales clerk at the Kresge’s five-and-dime store. Only a few people in town knew that this petite, shy, nice clerk had survived Titanic. “She rarely talked about her Titanic legacy,” Dick Warner of the Historical Society of Pottawattamie County told the Council Bluffs Nonpareil in 2012. “Most people who knew her weren’t even aware of it.”

Delaney died on January 26, 1982, at age 74 and was buried at St. Joseph Cemetery off McPherson Avenue in Council Bluffs. She was the only known passenger on Titanic to live in Council Bluffs.

Picture from the book “Not My Time to Die” by Lilly Setterdahl

“Life no longer has any value for me”

Like Delaney, many of Titanic’s survivors and victims were immigrants headed to America to begin a new life. In other cases, the travelers were only planning to visit before returning to Europe. Such was the story of second-class passenger Dagmar Lustig Bryhl, 20, who looked forward to attending a wedding in Red Oak, Iowa, and visiting her uncle Oscar Lustig in Rockford, Illinois, before returning to Sweden.

Author Lilly Setterdahl of East Moline, Illinois, has captured the often heartbreaking—and sometimes heroic—stories of Bryhl and the 122 other Swedes on board Titanic in her fascinating 2012 book, Not My Time to Die. I listened for any tidbits connected to Iowa as Setterdahl related many of these stories during the “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic” in Iowa City.

Consider the letter Bryhl wrote to her uncle while she recuperated in New York following the Titanic disaster (as documented in Not My Time to Die, page 119). Bryhl became so distraught that she wished she had been permitted to die on Titanic with her fiancé, Ingvar Enander, and brother, Kurt.

Dear Uncle,

Titanic has gone down. I don’t know whether my fiancé and my brother Kurt are saved. Evidently, they are not, for most of the men went under. I am at a hospital but am not sick, although very feeble. I have lost everything. I have no clothes, and so cannot get up, so must lie in bed for present.

I would have been glad if I had been permitted to die, because life no longer has any value for me since I lost my beloved. I feel myself so dreadfully alone in this land. These people are certainly good, but nevertheless do not understand me.”

Bryhl asked her uncle to come find her, which he did. Bryhl required bed rest after the long, tiresome journey to Rockford, and she refused to talk to reporters. Her uncle related bits and pieces of her story to local newspapers.

“I was in my berth when the Titanic hit the berg. I noticed the jar and soon I heard Ingvar [her fiancé] knocking on the door of my cabin.“Get up, Dagmar,” he said. “The ship has hit something.” I put on a skirt and coat as quickly as possible and hurried up to the deck. But the officers said, “Go back, there is no danger, you go to your cabins.”

Bryhl returned to her berth and went back to bed. Soon there was more knocking on her door.

“Get up, Dagmar, we are in danger!” Ingvar yelled. “I don’t care what the ship’s officers say. The boat is sinking.”

After pulling on her skirt and coat and running from her berth, Bryhl heard awful screaming and yelling. Women and children were being loaded into lifeboats. Men and women were kissing each other farewell. Ingvar and Kurt led Bryhl to a lifeboat, and Ingvar lifted his fiancé into the boat. She seized his hands and wouldn’t let go. “Come with me!” Bryhl screamed as loud as she could, still holding Ingvar’s hands tight. There was room in the lifeboat, which was only half full. Suddenly an officer ran forward and clubbed back Ingvar.

“This officer tore our hands apart, and the lifeboat was let down. As it went down, I looked up. There, leaning over the rail stood Kurt and Ingvar side by side. I screamed to them again, but it was no use. They waved their hands and smiled. That was the last glimpse I had of them.”

As the men in the lifeboat rowed the boat away from Titanic, the passengers shivered in the frigid night air as they watched the great ship sink.

“Then more dreadful screams,” said Bryhl, who recalled that the sea was so still it was clear as a mirror beneath the cloudless sky. “The water filled with crying people. Some of them climbed in our boat and so saved their lives.”

The small group of survivors huddled in the lifeboat until 6 a.m. on Monday, April 15, when the Carpathia arrived. Hours in the freezing air without adequate clothing to protect against the stinging cold numbed Bryhl’s body.

According to her uncle, Bryhl declared repeatedly between hysterical sobs that she never would have allowed her brother and fiancé to put her in the lifeboat if she thought the two men would be lost. She said she would rather have died with them when the great ship settled into the depths than to live with the memory of all that took place.

Bryhl returned home to Sweden in May 1912 after only a short time in Rockford. She later married a teacher named Eric Holmberg. She died in August 1969, Setterdahl noted.

“Not my time to die”

“Not my time to die”

During “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic,” Setterdahl (a native Swede herself) also detailed the life of 22-year-old Anna Nysten, the woman whose story provided the title for Setterdahl’s book.

Nysten had planned to leave Sweden in the summer of 1912 to visit her sister Klara in Passaic, New Jersey. However, some of Nysten’s friends who were headed to America that spring persuaded her to go with them. Nysten traveled with the Andersson family from Kisa, Sweden, and the Danbom family from Stanton, Iowa. Nysten would be the lone survivor of the 11-member group.

“I can hardly describe how it happened,” Nysten wrote to her parents in the wake of the Titanic disaster. “There was terrible screaming and groaning, but you and I ought to thank God that I am alive. I managed to get into a lifeboat because I don’t think it was my time to die. I’m supposed to experience more of the world.”

Nysten offered more details of the disaster after Titanic struck the iceberg (as documented in Not My Time to Die, pages 167-169).

“There was a terrible jolt, so we nearly fell out of bed. But then they said it was not serious, so the passengers calmed down until the ship began to sink and the deck was full of people.”

After someone took Nysten’s lifebelt and she began crying, a sailor gave her his life jacket. While her traveling companions proclaimed they would all go down together with the ship, a sailor pushed Nysten into a lifeboat.

“Oh, how terrible it was when everything went dark,” said Nysten, who recalled that her lifeboat could have held 63 people but only had about 40 passengers when it was lowered into the sea. “When the ship went down we were not far away and were almost sucked under.”

Nysten and the others in the lifeboat heard an awful rumbling noise as the great ship sank. They sat in the lifeboat from 1:30 a.m. to 6:30 a.m., but “fortunately the sea was calm,” she recalled.

“You can imagine how happy we were to see the steamer Carpathia close in on us and we could come aboard. They were so good to us.”

The survivors were given blankets, coffee and brandy (“as much as we wanted,” Nysten noted).

“But there was still much groaning and crying because most of us had lost a dear relative,” Nysten recalled. “Many became hysterical.”

In New York, Nysten was taken to the Swedish Immigrant Home, where she received $25 from the Women’s Relief Committee. Nysten spent three years in New York with friends and intended to return to Sweden, but when the Lusitania was torpedoed in 1915, she changed her mind. She came to Boone, Iowa, and moved to Des Moines in 1916, where she married Arvid Gustafson in 1917. The couple had three sons and were members of the First Lutheran Church in Des Moines.

Nysten was one of the few Titanic survivors who married, had children and was not reluctant to talk about her Titanic experience, although it took several years after the sinking before she was willing to share many of those haunting memories, Setterdahl noted. In 1937 on the 25th anniversary of the tragedy, Nysten said in a newspaper interview that she no longer dreamed about the disaster.

Nysten passed away March 28, 1977, and is buried in Resthaven Cemetery in West Des Moines.

“The lifeboats were all gone”

Some Swedes on the Titanic like Gunnar Tenglin were returning to their adopted home in Iowa. Tenglin, 25, had grown up in Sweden and emigrated to America around 1903 at age 16. He settled in Burlington, Iowa. Until he learned to speak English he worked with crews cutting ice on the Mississippi River. He learned English while working at the Horace Patterson farm.

Tenglin returned to Sweden in 1908 where he married his wife, Anna. A year after the couple’s son, Gunnar, was born in Stockholm in 1911, Tenglin made plans to return to Burlington. He acquired a third-class ticket to travel on Titanic. Tenglin considered third class on Titanic equal to first class on most other steamers, noted Setterdahl, who documents his story in Not My Time to Die, pages 191-194.

Late in the evening of April 14, 1912, Tenglin and his traveling companion, August Wennerstrom (a fellow Swede who would also survive the sinking) had come back from a party on board Titanic. Tenglin had just taken off his shoes and was preparing for bed when he felt a thud. He put his jacket on but left his shoes in his bunk and his lifejacket under his pillow. He never returned for them.

When he came up on deck, all the lifeboats were gone. An officer on deck engaged Tenglin as an interpreter since the Swede knew English. Tenglin thought that saved him, as noted in a 2012 Burlington Hawk Eye article, because he was still on deck translating the officer’s commands to other Swedes. Otherwise, he may have been below deck when the ship when down.

Tenglin, a tall man of medium build with light blue eyes and brown hair, provided specific details of that unforgettable night to the Burlington Daily Gazette in 1912:

“It looked to us as if we were doomed to perish with the ship when a collapsible lifeboat was discovered. This boat would hold about 50 people, and we had considerable trouble getting it loose from its fastenings. The boat was on the second deck, and the ship settled the question of its launching, as the water suddenly came up over the deck and the boat floated.”

The terror was far from over, though.

“There must have been 150 people swimming around or clinging to the boat, and we feared it would collapse or sink,” Tenglin said. “We had no oars or anything else to handle the boat and were at the mercy of the waves, but the sea was calm.”

There was no way to sit down, so the boats passengers stood up in knee-deep, ice-cold water. Basic survival instincts dominated the horrific scene.

“Those on the edges pushed the frantic people in the water back to their fates, it being feared they would doom us all,” Tenglin said.

A big Swede named Johnson was kept busy throwing corpses overboard, Tenglin added, since the survivors wanted to make the boat as light as possible to increase its buoyancy.

Tenglin and other passengers in Collapsible A were rescued by the Carpathia. When the ship arrived in New York, the American Red Cross and the Swedish American Society took pictures of the surviving immigrants and printed the images as picture postcards. Tenglin sent one of those postcards to his mother in Sweden, mailing it from Burlington on April 29, 1912.

Tenglin lived the rest of his life in Iowa, where he was joined by his wife and son who arrived from Sweden in 1913. Tenglin worked various jobs during his career, from the railroad to the local utility plant that supplied Burlington with gas. Tenglin passed away in 1974 at age 86 in Burlington and is buried in Aspen Grove Cemetery.

Immigrant recruiter buried in Stanton, Iowa

Immigrant recruiter buried in Stanton, Iowa

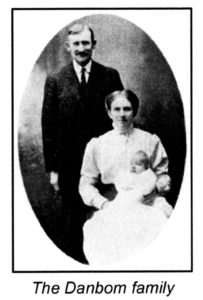

Other Swedes on board Titanic did not have the opportunity to live a long, full life. On pages 231-233 of Not My Time to Die, Setterdahl relates the sad fate of Ernest Danbom, a 34-year-old farmer and immigrant recruiter who was born and raised in Montgomery County, Iowa.

The son of two Swedish immigrants who farmed in southwest Iowa, Danbom married his wife, Anna, in 1910. The newlyweds traveled to Sweden for their honeymoon and remained with Anna’s family for a number of months. During this time, Anna gave birth to the couple’s son, Gilbert, in Kisa, Sweden, on November 16, 1911.

By April 1912, the young family prepared to return to America. Danbom also assumed the role of tour conductor for a group of 11 Swedes (including Anna Nysten and the Andersson family) who were traveling on Titanic.

As an immigrant recruiter, Danbom received a commission from each person he encouraged to come to America. Even after paying approximately $68 for a family cabin on Titanic, Danbom was carrying a substantial amount of money (including $276 in cash and $30 in gold) when he left Sweden, according to Not My Time to Die. He hoped that the money would help his family acquire a fruit farm in Turlock, California.

Tragically, none of the young family would survive the sinking of Titanic. Danbom’s wife and young son were lost at sea. Danbom’s body was recovered and brought to Halifax in Canada before being sent to Stanton, Iowa, for burial.

The Halifax coroner listed among his personal effects a black overcoat, dark suit, white pleated shirt, black boots, wedding ring marked “S.B.T.E.G.D., June 6, ’10,” gold watch and chain, knife, keys, opal and ruby ring, fountain pen, bracelet, ladies watch and chain, 3 memo books, solitaire diamond ring, scissors, U.S. naturalization papers, pocketbook, jewel case, and a check for $1,315.79, Security Bank, Sioux City.

Danbom is buried in the cemetery in Stanton. The inscription on his tombstone reads, “Ernest Danbom, 26 Oct 1877, died 15 April 1912, in Titanic disaster, his remains were recovered from the ocean. “Nearer My God to Thee.”

“No, I must be a gentleman”

In Cedar Rapids, attention focused on the well-known Douglas family, who endured an excruciating wait to learn the fate of Walter Douglas, 50, and his second wife, Mahala, first-class passengers on Titanic.

Walter Douglas was son of the founding partner of The Quaker Oats Company in Cedar Rapids. In 1903, Douglas and his brother George, founded the Douglas Starch Works, which produced cooking starch and oil, laundry starch, animal feed, soap stock and industrial starches.

After celebrating Christmas 1911 with the Douglas family at the Brucemore mansion in Cedar Rapids, Walter and Mahala traveled to Europe for a three-month vacation to celebrate Walter’s retirement, according to Brucemore historic site and community cultural center, which has preserved this history. While in Europe, the couple also purchased furnishings for their mansion on a bluff overlooking Lake Minnetonka near Minneapolis, Minnesota.

After celebrating Christmas 1911 with the Douglas family at the Brucemore mansion in Cedar Rapids, Walter and Mahala traveled to Europe for a three-month vacation to celebrate Walter’s retirement, according to Brucemore historic site and community cultural center, which has preserved this history. While in Europe, the couple also purchased furnishings for their mansion on a bluff overlooking Lake Minnetonka near Minneapolis, Minnesota.

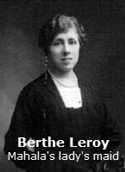

The couple bought first-class tickets for themselves and their French maid, Berthe Leroy, to return home aboard Titanic in time to celebrate Walter’s birthday on April 21 with family. First-class tickets on Titanic ranged from roughly $150 for a simple berth–about $3,600 today, based on current inflation tables, to $4,350 (more than $100,000) for one of the two Parlour suites.

On the night Titanic struck the iceberg, Walter and Mahala had just returned to their suite from the first-class dining room when they heard the engines stop. After Mahala asked Walter to find out what was going on, she donned her fur coat and boots to wait in the hallway. Seeing no officers and receiving no orders, Mahala grew concerned and returned to her cabin for a life preserver. Walter returned and teased her about the preserver, but agreed they should go on deck together. The couple watched as the distress rockets shot high into the air and burst into a shower of light.

Passengers on deck remained calm as they boarded the lifeboats. As Mahala climbed into a lifeboat, she requested that Walter join her. “No, I must be a gentleman,” he said before joining a group of men waiting for another lifeboat. Dressed in his tuxedo, Walter was last seen helping women and children into the final lifeboats.

After Titanic sank, initial reports of the disaster were sparse and contradictory. The limits of wireless communication and the isolation of the disaster limited accurate information. When news of the tragedy reached Cedar Rapids, the magnitude of the disaster and the fate of Walter and Mahala were unknown.

After Titanic sank, initial reports of the disaster were sparse and contradictory. The limits of wireless communication and the isolation of the disaster limited accurate information. When news of the tragedy reached Cedar Rapids, the magnitude of the disaster and the fate of Walter and Mahala were unknown.

“The news of Titanic’s disaster came at noon while we were at luncheon,” noted an April 15 diary entry written by Irene Douglas, Walter’s sister-in-law who lived at Brucemore. “Did not seem serious until evening about 7:30 – spent the evening at the [Cedar Rapids] Republican [newspaper] office.”

Hearing no news, Irene and her husband, George, left Cedar Rapids on April 16 to meet the Carpathia, which was carrying Titanic survivors to New York. On April 17, the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette reported:

“Up to 1 o’clock today no definite news had been received in Cedar Rapids concerning the fate of Mr. Walter D. Douglas…. The wireless telegraph companies having great trouble in effecting communication with the Carpathia…. It appears that a considerable number of the first and second cabin passengers, especially the men, must have perished, but it is still hoped that Mr. Douglas was among the ones rescued. Mrs. Douglas is on the Carpathia, but whether Mr. Douglas went down with the boat, as did many others of the male passengers, remains to be determined.”

On April 18, thousands of people waited in the rain in New York as the ship bearing approximately 700 Titanic survivors slowly approached the dock.

“Carpathia landed 7 in the eve.,” Irene noted in her diary. “Walter not with Mahala.”

Eight days after the sinking, the Douglas family received word on April 23 that Walter’s body had been recovered by the cable ship MacKay Bennett, the same ship that recovered the body of Wallace Hartley, whose seven-member band played as Titanic sank.

The Mackay-Bennett recovered 306 bodies near the scene of the sinking, including the body of Walt er Douglas, who was identified by his monogrammed shirt and cigarette case. The ship’s crew recorded the following information:

er Douglas, who was identified by his monogrammed shirt and cigarette case. The ship’s crew recorded the following information:

• No. 62 – MALE – Estimated age, 55 – Hair grey

• Clothing – Evening dress, with “W.D.D.” on shirt.

• Effects – Gold watch; chain; gold cigarette case “W.D.D.”; five gold studs; wedding ring on finger engraved “May 19th ’84”; pocket letter case with $551

(Interesting side note: The Mackay-Bennett was at sea working on a French trans-Atlantic cable when it got the charter from Titanic’s owners, White Star Line, to join the recovery efforts. After returning to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in Canada to pick up a hold full of ice to refrigerate bodies, 100 coffins, canvas sacks, an undertaker, and embalming fluids and equipment, the Mackay-Bennett headed out to sea to search for Titanic victims in a mission continually hampered by fog, heavy waves and wind. With its supply of coffins quickly filled and a steady stream of bodies being brought aboard by crewmen who went out in lifeboats, the Mackay-Bennett had to borrow canvas sacks and more embalming supplies from other recovery ships. The Mackay-Bennett buried at sea 116 of the 306 bodies it recovered, likely because they were not in good enough shape to be taken to Halifax. The ship took 190 victims to Halifax, where unclaimed bodies were buried in various cemeteries.)

Walter Douglas’ remains were taken first to his home in Minneapolis, then via a special train to Cedar Rapids for entombment in the Douglas family vault at Oak Hill Cemetery.

Mahala returned to her home on Lake Minnetonka, accompanied only by her maid, Berthe Leroy. An advocate of arts and culture, Mahala supported many local charities and made a donation in Walter’s name to Coe College in Cedar Rapids. A talented writer, Mahala published a collection of stories and poems in 1932. One copy, inscribed to George and Irene Douglas, is stored in the Brucemore archives. The last poem in the book is a haunting account of Titanic’s demise.

Titanic

The sea velvet smooth, blue-black,

The sky set thick with stars unbelievably brilliant.

The horizon a clean-cut circle.

The air motionless, cold – cold as death.

Boundless space.

A small boat waiting, waiting in this vast stillness,

Waiting heart-breakingly.

In the offing a vast ship, light streaming from her portholes.

Her prow on an incline.

Darkness comes to her suddenly.

The huge black hulk stands out in silhouette against the star-lit sky.

Silently the prow sinks deeper,

As if some Titan’s hand,

Inexorable as Fate,

Were drawing the great ship down to her death.

Slowly, slowly, with hardly a ripple

Of that velvet sea,

She sinks out of sight.

Then that vast emptiness

Was suddenly rent

With a terrifying sound.

It rose like a column of heavy smoke.

It was so strong, so imploring, so insistent

One thought it would even reach

The throne of grace on high.

Slowly it lost its force,

Thinned to a tiny wisp of sound,

Then to a pitiful whisper….

Silence.

Food for thought as Titanic’s legacy lives on

Food for thought as Titanic’s legacy lives on

While more than 100 years have passed since Titanic plunged to the bottom of the sea, interest in the magnificent ship never wanes. In fact, Titanic II, a faithful replica of the doomed ship, is preparing for passengers by 2018.

The brainchild of Australian billionaire Clive Palmer, Titanic II will have practically the same dimensions of the original Titanic, which would be on the smaller side of modern cruise ships. (Shrewdly, the Titanic II will have more lifeboat capacity than the original ship.)

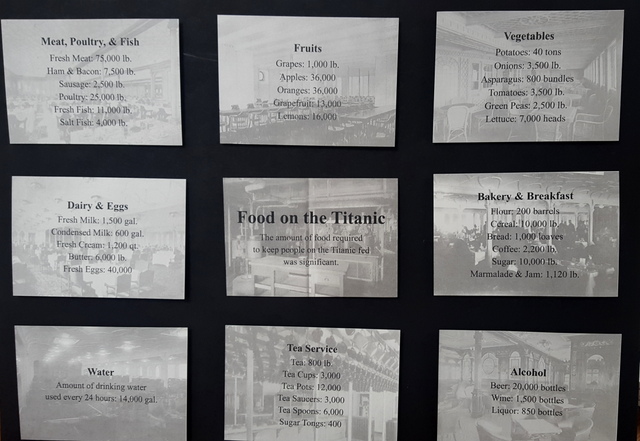

When Titanic II makes its maiden voyage from Jiangsu, China, to Dubai, no doubt it will offer exceptional meals, just as its predecessor did. The original Titanic’s provisions included 75,000 pounds of fresh meat, 11,000 pounds of fresh fish, 4,000 pounds of salted and dried fish, 7,500 pounds of bacon and ham, 40,000 fresh eggs, 40 tons of potatoes, 2,200 pounds of coffee, 10,000 pounds of sugar and 250 barrels of flour.

When I sampled an unforgettable taste of Titanic in Iowa City during the Johnson County Historical Society’s “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic,” one of my favorite menu items was the Victoria Sponge Cake.

“This cake is everyone’s favorite,” declares Penelope Carlevato in her book Tea on the Titanic: 100 Years Later. “No leftovers when you serve this cake.” I can see why, especially with this cake’s light texture and sweet filling that’s perfect with homemade jam (my favorite) or your best store-brought preserves.

Victoria Sponge Cake served at the Johnson County Historical Society’s “Afternoon Tea on the Titanic” in Iowa City on April 2, 2017

Victoria Sponge Cake

Cake:

1 cup unsalted butter (at room temperature)

1 cup granulated sugar

4 eggs, beaten

2 cups self-rising flour, sifted flour

Filling:

1 cup jam, preserves or lemon curd (or whipping cream, if you desire)

Powdered sugar

Cream butter and sugar until light and fluffy. Add eggs and mix well. Grease and line two 8-inch round cake pans with parchment paper. Divide batter between the pans and smooth the tops for evenness.

Bake 20 to 25 minutes at 375 degrees Fahrenheit. Cool for 10 to 15 minutes in pans; then turn cakes out onto wire racks to continue cooling.

Place a paper doily on a footed cake plate. Sandwich bottoms of cake together with jam or preserves (strawberry preserves, raspberry preserves or apricot jam work well). Whipping cream could be substituted for the jam, if desired. Sprinkle top of cake with powdered sugar.

Decorate cake plate with chemical-free flowers such as violets or nasturtiums, if desired. (Wash the flowers well before use.)

Want more Iowa culture and history?

Read more of my blog posts if you want more Iowa stories, history and recipes, as well as tips to make you a better communicator.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too. Coming soon in September 2017–my third Iowa history book! Watch for more details on “Dallas County” from Arcadia Publishing.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

7 responses to “Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic”

Recent Posts

- Do Press Releases Still Work?

- Erasing History? Budget Cuts Threaten to Gut Ag History at Iowa State University

- Machines that Changed America: John Froelich Invents the First Tractor in Iowa

- Bob Feller on Farming, Baseball and Military Service

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

Categories

- Achitecture

- Agriculture

- Architecture

- baking

- barbeque

- Barn

- breakfast

- Business

- Communication Tips

- Conservation

- content

- cooking

- Crime

- Dallas County

- Economical

- Farm

- Featured

- Food

- Food history

- health

- Iowa

- Iowa food

- Iowa history

- marketing

- Photography

- Recipes

- Seasonal

- Small town

- Storytelling

- Uncategorized

- writing

Archive by year

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- When Agriculture Entered the Long Depression in the Early 1920s

- The Corn Lady: Jessie Field Shambaugh and the Birth of 4-H in Iowa

- Sauce to Sanitizer: Cookies Food Products Bottles Hand Sanitizer Made with Ethanol

- Myth Busting: No, Your Pork Doesn't Come from China

- Long Live Print Newsletters! 5 Keys to Content Marketing Success

- Shattering Silence: Farmer Helped Slave Find Freedom and Racial Equality in Iowa

- Meet Iowa Farmer James Jordan, Underground Railroad Conductor

- George Washington Carver Rose from Slavery to Ag Scientist

- Remembering the African-American Sioux City Ghosts Fast-Pitch Softball Team

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- 2019

- The Untold Story of Iowa’s Ag Drainage Systems

- Stop Rumors Before They Ruin Your Brand

- Finding Your Voice: The Story You Never Knew About "I Have a Dream"

- Warm Up with Homemade Macaroni and Cheese Soup

- Can a True Story Well Told Turn You into a Tom Brady Fan?

- Baking is for Sharing: Best Bread, Grandma Ruby’s Cookies and Other Iowa Favorites

- 4 Key Lessons from Bud Light’s Super Bowl Corn-troversy

- Could Your Story Change Someone’s Life?

- What To Do When the Travel Channel Calls

- Tex-Mex Sloppy Joes and the Magic of Maid-Rite in Iowa

- How Not to Invite Someone to Your Next Event--and 3 Solutions

- We Need FFA: Iowa Ag Secretary Mike Naig Reflects on His FFA Experiences

- From My Kitchen to Yours: Comfort Food, Conversation and Living History Farms

- Smart Marketing Lessons from an Uber Driver--Listen Up!

- Hog Trailers to Humidors: Two New Iowa Convenience Stores Reflect “Waspy’s Way”

- A Dirty Tip to Make Your Social Media Content More Shareable

- Are You on Team Cinnamon Roll?

- Senator Grassley on Farming: Any Society is Only Nine Meals Away From a Revolution

- Why We Should Never Stop Asking Why

- What’s the Scoop? Expanded Wells’ Ice Cream Parlor Offers a Taste of Iowa

- Independence, Iowa’s Connection to the Titanic and Carpathia

- Memories of Carroll County, Iowa, Century Farm Endure

- Iowa's “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

- 2018

- How to Cook a Perfect Prime Rib

- How Did We Get So Rude?

- Mmm, Mmm Good: Soup’s on at the Rockwell City Fire Department

- Quit Using “Stupid Language”

- In Praise of Ham and Bean Soup

- Recalling a Most Unconventional—and Life-Changing--FFA Journey

- Events Spark Stories That Help Backcountry Winery Grow in Iowa

- Sac County Barn Quilt Attracts National Attention

- Doing Good, Eating Good at Lytton Town Night

- Young Entrepreneur Grows a Healthy Business in Small-Town Iowa

- Digging Deeper: Volunteers Showcase Thomas Jefferson Gardens in Iowa

- How to Tell Your Community’s Story—with Style!

- DNA Helps Sailor Killed at Pearl Harbor Return to His Family

- It’s Time to Be 20 Again: Take a Road Trip on Historic Highway 20

- The Biggest Reason You Shouldn’t Slash Your Marketing Budget in Tough Times

- Are You Telling a Horror Story of Your Business?

- Pieced Together: Barn Quilt Documentary Features Iowa Stories

- Unwrapping Storytelling Tips from the Candy Bomber

- Barn Helped Inspire Master Craftsman to Create Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

- Butter Sculptures to Christmas Ornaments: Waterloo Boy Tractor Celebrates 100 Years

- Ag-Vocating Worldwide: Top 10 Tips for Sharing Ag’s Story with Consumers

- 2017

- Growing with Grow: Iowa 4-H Leader Guides 100-Year-Old 4-H Club for 50 Years

- High-Octane Achiever: Ethanol Fuels New Driver Tiffany Poen

- Shakespeare Club Maintains 123 Years of Good Taste in Small-Town Iowa

- Iowa’s Ice Queen: Entrepreneur Caroline Fischer’s Legacy Endures at Hotel Julien Dubuque

- Darcy's Bill of Assertive Rights: How to Communicate and Get What You Need

- Celebrating Pi Day in Iowa with Old-Fashioned Chicken Pot Pie

- Cooking with Iowa’s Radio Homemakers

- Top 10 Tips to Find the Right Writer to Tell Your Company’s Stories

- The “No BS” Way to Protect Yourself from Rude, Obnoxious People

- Learning from the Land: 9 Surprising Ways Farmers Make Conservation a Priority

- Leftover Ham? Make This Amazing Crustless Spinach and Ham Quiche

- Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic

- Coming Soon--"Dallas County," a New Iowa History Book!

- How to Clean a Burned Pan in 6 Simple Steps

- Iowa Beef Booster: Larry Irwin Takes a New Twist on Burgers

- Get Your Grill On: How to Build a Better Burger

- "Thank God It’s Over:" Iowa Veteran Recalls the Final Days of World War 2

- How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service

- Imagine That! Writers, Put Your Reader Right in the Action

- Remembering Ambassador Branstad’s Legacy from the 1980s Farm Crisis in Iowa

- Busting the Iowa Butter Gang

- Lightner on Leadership: “Everyone Has Something to Give”

- Show Up, Speak Up, Don’t Give Up

- Small - Town Iowa Polo Teams Thrilled Depression - Era Crowd

- Ethanol:Passion by the Gallon

- Cruising Through Forgotten Iowa History on Lincoln Highway

- Why I'm Using a Powerful 500-Year-Old Technology to Make History--And You Can, Too

- 5 Ways a “History Head” Mindset Helps You Think Big

- Behind the Scene at Iowa's Own Market to Market

- Let’s Have an Iowa Potluck with a Side of History!

- Iconic State Fair Architecture: Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iconic State Fair Architecture- Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iowa Underground - How Coal Mining Fueled Dallas County's Growth

- Ultra-Local Eating: Jennifer Miller Guides CSA, Iowa Food Cooperative

- The Hotel Pattee and I are Hosting a Party—And You’re Invited!

- Tell Your Story—But How?

- Mediterranean Delights: Iowa Ag Influences Syrian-Lebanese Church Dinner

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations!

- 6 Ways to Motivate Yourself to Write—Even When You’re Not in the Mood

- Always Alert-How to Stay Safe in Any Situation

- Does Accuracy Even Matter Anymore?

- Soy Power Shines at Historic Rainbow Bridge

- Free Gifts! (Let’s Talk Listening, Stories and History)

- 2016

- How to Connect with Anyone: Lessons from a Tornado

- Soul Food: Lenten Luncheons Carry on 45-Year Iowa Tradition

- Top 3 Tips for Writing a Must-Read Article

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips to Better Writing

- Top 8 Tips for Building a Successful Freelance Business

- 10 Steps to Better Photos

- Reinventing the Marketer of 2010

- Extreme Writing Makeover

- My Top Social Media Tips for Farmers: REVEALED!

- Honoring the Legacy of Rural Iowa's Greatest Generation

- Iowa's Orphan Train Heritage

- Dedham’s Famous Bologna Turns 100: Kitt Family Offers a Taste of Iowa History

- Iowa Barn Honors Pioneer Stock Farm

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips for Better Photos

- Soup and Small-Town Iowa Spirit

- Savoring the Memories: Van's Café Served Up Comfort Food for Six Decades

- Mayday, Mayday—The Lost History of May Poles and May Baskets in Iowa

- Iowa's Vigilante Crime Fighters of the 1920s and 1930s

- Very Veggie: Iowan's Farm-Fresh Recipes Offer Guilt-Free Eating

- Iowa Public TV's "Market to Market" Features Expedition Yetter, Agri-Tourism, Des Moines Water Works' Lawsuit

- 62 Years and Counting: Calhoun County, Iowa, Families Maintain 4th of July Picnic Tradition

- “A Culinary History of Iowa” Satisfies: Iowa History Journal Book Review

- For the Love of Baking: Lake City's Ellis Family Showcases Favorite Iowa Farm Recipes (Caramel Rolls, Pumpkin Bars and More!)

- Remembering Sept. 11: Iowa Community’s Potluck Honors America

- Talking Iowa Food and Culinary History on Iowa Public Radio

- Talking "Stilettos in the Cornfield," Taxes, Trade and More on CNBC

- FarmHer #RootedinAg Spotlight--FFA Attracts More Women to Careers in Ag

- Rustic Cooking Refined: Iowan Robin Qualy Embraces Global Flavors

- Voice of Reason: Iowa Pork Producer Dave Struthers Offers Top 10 Tips to Speak Up for Ag

- Iowa Eats! Why Radio Iowa, Newspapers and Libraries are Hungry for "A Culinary History of Iowa"

- Iowa Turkeys Carry on National Thanksgiving Tradition

- Riding with Harry: 2016 Presidential Election Reflects Truman's Iowa Revival at 1948 Plowing Match in Dexter

- All Aboard! Rockwell City’s “Depot People” Offer a Taste of Iowa History

- Is This Iowa's Favorite Appetizer?

- O, Christmas Tree! Small Iowa Towns Celebrate with Trees in the Middle of the Street

- Slaves Escaped Through Dallas County on Iowa’s Underground Railroad

- Adel Barn Accents Penoach Winery in Iowa

- Celebrating New Year's Eve in Style at a Classic Iowa Ballroom

Thank you for sharing these stories. I had never heard of anyone from Iowa having a Titanic connection. I even grew up in SW Iowa and had never heard.

You’re welcome, Amy! Glad you enjoyed the post. I myself learned a lot about Iowa history by researching this story. Amazing, isn’t it, how many ties Iowa had to the Titanic–and how so much of this history has been forgotten? Glad I can help keep these stories alive!

One of the scientists, who did so much to find the Titanic, Robert Ballard by name, didn t want the treasure hunters to find the ship.

Edmond from his estranged wife, assumed the name Louis M. Hoffman and boarded the ship in Southampton, intent on taking his children to the United States.

I really enjoyed reading about the Iowa Connections on the Titanic and the Orphan Train. I am a retired third grade teacher and presented both topics as units in my classroom. The children were always so interested. I love reading the real stories….thank you

Great read. Information such as this should not be lost and so with that said thank you for compiling and carrying it on. Informative and interesting piece Darcy. Kudos!

Thanks so much, Angela. I truly appreciate your kind words.