Whats HOT

Latest Posts

Are You on Team Cinnamon Roll?

It’s every marketer’s dream–a topic so compelling that no one can ignore it, and everyone wants to talk about it. Here in Iowa, this kind of topic revolves around that school-lunch classic–chili and cinnamon rolls.

Yep, it’s a thing, and it’s a beloved tradition here in my hometown of Lake City. I’ll never forget the comforting aroma of homemade rolls (caramel rolls, most of the time) filling the school, including our 1920s-vintage three-story high school. As if it weren’t hard enough to concentrate in math class, I had that enticing aroma to distract me–but oh what sweet torture!

I’m reliably informed that chili and cinnamon rolls are still a favorite school lunch in the local school district, as well as other schools around the state.

So when it was time to write the manuscript for my second book, “A Culinary History of Iowa,” I started talking to sources about the history of chili and cinnamon rolls. Not only did I discover that no one seems to remember the origins of this phenomenal combo, but it’s not something that every Iowa school kid grew up with.

Some people had never heard of it. Others said their school served peanut butter sandwiches with chili. There were those who couldn’t imagine chili without cornbread. Still others, including a friend from Minnesota, were revolted. “That makes no sense! That’s like eating scrambled eggs and birthday cake together!” said one Minnesota native.

Whether you love it or hate it, seems like everyone has an opinion about chili and cinnamon rolls. Click here for a snippet from my Culinary History of Iowa book to help whet your appetite about the history of chili and cinnamon rolls–along with an amazing recipe!

This food combo is also a surprisingly newsworthy topic. A reporter from the Des Moines Register interviewed me for the recent article “The history behind Iowa’s unique taste for chili and cinnamon rolls.”

The day after that story ran, I received an email from Jodi Long, a reporter for TV-13, the NBC affiliate in Des Moines. She wanted to do a segment on the history of chili and cinnamon rolls, so we filmed the segment last Friday. As soon as it aired on the early morning news segment this past Monday, I started getting comments, kudos and questions on Facebook and beyond.

(I love the Team Cinnamon Roll and Team Cornbread idea that Jodi included in her Facebook post. To watch the news segment, click here!)

I learned three things from this experience:

1. Realize that things you take for granted might be quite newsworthy, and look for ways to showcase these stories. (Your website, newsletter, e-newsletter, social media posts, press releases, videos, podcast or other communication tools might be just the place to share these stories.)

2. Respond quickly when the media wants to interview you about a topic. Reporters need to know sooner rather than later whether you can help them. Don’t miss the opportunity for free publicity.

3. Invite people to join the conversation. So I want to know–are you on Team Cinnamon Roll or Team Cornbread?

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2019 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

Smart Marketing Lessons from an Uber Driver–Listen Up!

Ever used Uber? If you have, I bet your ride was in a city. One of my entrepreneurial friends, Pat, recently started driving for Uber and Lyft here in rural Iowa. Through smart marketing, he’s carving quite a niche.

“I really didn’t realize how much influence the driver has,” Pat told me recently. The other evening, for example, he picked up two guys in a northern Iowa community who said they wanted a ride to the local casual dining/sports bar hangout several blocks away. Then Pat asked, “What do you want to do, eat wings or party?”

“Party!”

“Then we’ll go to a party bar,” Pat said. They agreed, and he drove them 2 miles down the road. He also picked them up again when they were ready to leave.

I love this story, because it highlights some basic keys to successful marketing:

• Take the time to ask the right questions.

• Listen carefully to the answers.

• Help clients reach their goals.

“See, you’re adding value!” I told Pat. “That’s what a great marketer does. You asked the right questions to get to the core of what these guys really wanted, plus you put more money in your pocket. Bravo!”

Marketing takeaway: Asking questions and listening are essential to successful marketing. What key questions do you ask your clients/prospects? Are there more questions you can ask to better serve their needs and become the business partner of choice?

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2019 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

We Need FFA: Iowa Ag Secretary Mike Naig Reflects on His FFA Experiences

When you look at his formative years, my friend Mike Naig shouldn’t be where he is today, serving as Iowa’s Secretary of Agriculture. Even for him, it’s hard to shake memories of the Farm Crisis.

“As a child of the 1980s, I knew my parents didn’t want us to go through the same hardships they did,” said Naig, 40, the third of four Naig children who grew up on their family’s farm near Cylinder in northwest Iowa. “There was this mentality of ‘go do something other than farming,’ so my siblings and I were going to college and pursue careers off the farm.”

Naig considered studying veterinary medicine or a major related to human health. Yet there was something that planted a seed back then in Palo Alto County, something that would take root and shape Naig’s future in ways he could never imagine. That transformative experience was FFA.

“I never predicted I’d serve in a role like this, but I’m grateful for the life skills and ag knowledge I learned in FFA,” said Naig, who is one of Iowa’s most high-profile champions of FFA, especially during National FFA Week from February 16-23, 2019. “We need FFA.”

Naig speaks from experience. Before serving as Iowa’s Secretary of Agriculture, this Buena Vista University graduate worked in agribusiness for more than 13 years, serving in public policy roles for state and national trade associations and in private industry. He served as the Iowa Deputy Secretary of Agriculture under Bill Northey starting in September 2013.

When Northey joined the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds appointed Naig to succeed Northey as Iowa Secretary of Agriculture on March 5, 2018. Naig was elected Secretary of Agriculture in November 2018. Here’s his story:

Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig

Q: How did your leadership journey begin?

A: Before I joined FFA, I was heavily involved in 4-H. The first meeting I ever chaired was at my local Independence Boosters 4-H Club. I stayed involved in 4-H through high school and served in all the officer roles. I also served on the 4-H Youth County Council in Palo Alto County. During high school, I went on a leadership trip to Washington, D.C. This helped spark my interest in government and politics.

Q: What role did FFA play in your years at Emmetsburg High School?

A: While I was involved with the student council and served as student body president in high school, I was really into soil judging with FFA. Before I graduated from high school in 1996, our soil judging team made it to state and then to the national competition in Oklahoma. All this fit well with my interest in science, soil quality and soil health. Those of us in FFA were fortunate to have a strong FFA chapter, a great advisor, Jerry Strand, and a supportive community. Although I didn’t know it back then, all this would provide a strong background for my career when I started working on soil and water quality policy issues.

Q: What lessons did you learn from your FFA experiences?

A: FFA teaches you that preparation pays off. The supervised agricultural experience (SAE) challenges you to come up with a project and see it through. This requires you to get organized, plan ahead and think strategically. For many kids, this is one of the first big tastes of responsibility they get. You also learn teamwork, since you have to work together to get things done. Competition is also important in FFA. You learn to put your best effort forward and win with grace. If you come up short, you learn from your mistakes and are encouraged to do better next time.

Q: How can FFA help Iowa meet the challenges of the twenty-first century?

A: FFA does a great job of helping kids learn about the rewarding, ag-related careers that are available in a variety of disciplines right here in Iowa. FFA also does an outstanding job of developing the next generation of ag leaders. This is important, because I see “volunteer fatigue” in many communities. There are plenty of opportunities to serve, including local churches, school boards, county Farm Bureau boards, co-op boards and hospital boards, but it can be hard to replace dedicated board members and volunteers who have served so well for many years. We have significant needs in our rural communities across the state, and we’ll need leaders like those in FFA today to step up and fill these important roles going forward.

Q: What excites you about the future of FFA and Iowa?

A: While these are challenging times in agriculture, there’s always reason for hope. Protein demand worldwide is growing, along with demand for bio-based fuels. Technology continues to advance and create new opportunities. There’s so much we have yet to discover in agriculture, which is exciting!

Iowa is at the epicenter of all this. We have something very special here, and it’s not just our rich soil. It’s our people. Rural Iowa can thrive when it’s guided by lifelong learners who are focused on continuous improvement to protect our precious natural resources and expand economic opportunities. FFA members will be part of this future, guided by the knowledge that feeding people is a noble profession. FFA has a strong record of developing leaders. It’s essential we keep FFA and ag education strong in our schools.

Forever proud to wear the iconic FFA blue jacket!

A note from Darcy:

I appreciate Mike’s comments about the importance of FFA and ag education for this story, which first appeared in Farm News. FFA played a critical role in helping me find my career, but boy, was it a strange, wacky, wonderful journey. Read the whole crazy story here.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2019 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

The Untold Story of Iowa’s Ag Drainage Systems

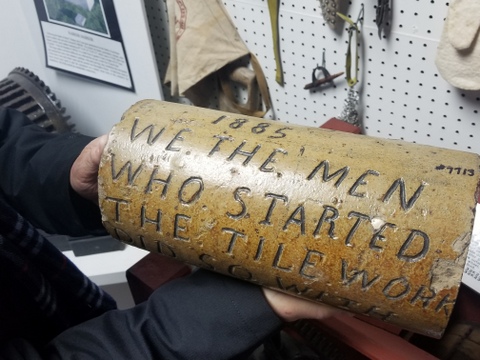

If there were a “Mysteries at the Museum” television series geared towards agriculture, this item would be ideal to lead in a segment. It’s hollow, it’s made of clay, it contains a message from the past, and it was buried in the ground for decades.

It’s a unique clay drainage tile dated 1885, and it’s on display in the Greene County Historical Society’s museum in Jefferson. The message carved around the exterior of the tile reads, “We the men who started the tile work did so with a motive to benefit the town and country. Signed T.P. LaRue of Scranton, Iowa.”

An interpretive sign by the tile shares a quote from S.J. Melson, a former Greene County engineer, to explain the curious item’s history. “This tile was placed into my hands by Carl Paup on February 1968. Mr. Paup stated the tile was unearthed and has lasted for many years on the property owned and operated by Harrison Paup of Kendrick Township, Greene County, Iowa.”

That tile reflects a major part of Iowa’s agricultural history that has been buried, literally, for generations, yet this history continues to influence farming methods, especially in the prairie pothole regions of north-central Iowa and northwest Iowa.

“In general, ag drainage in Iowa got its start around 1880, but this varied a lot, depending on the region,” said Joe Otto, a historian and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Oklahoma who works as a communications specialist with the Iowa Water Center at Iowa State University.

The first documented case of a drain tile being installed in Iowa occurred in 1868 on the grounds of Iowa State in Ames, Otto added. Before that, some of the first drainage ditches were dug in the 1850s along the Mississippi River in Des Moines County, just upstream from Burlington, so farmers could help protect themselves from flooding. One of these farmers, John Williams, was later elected to the state legislature and helped get the state’s first drainage laws passed in the 1870s, Otto said.

Drainage affected Iowa’s settlement patterns

Ag drainage was such a major issue in the 1800s that it impacted Iowa’s settlement. “Iowa wasn’t settled east to west, but from the bottoms up to the top of the state’s many river valleys,” Otto said. “Atop the river valleys were the flat, glaciated prairies of north-central and northwestern Iowa. These were settled and farmed starting in the 1870s and 1880s – several decades after farming started along the Mississippi.”

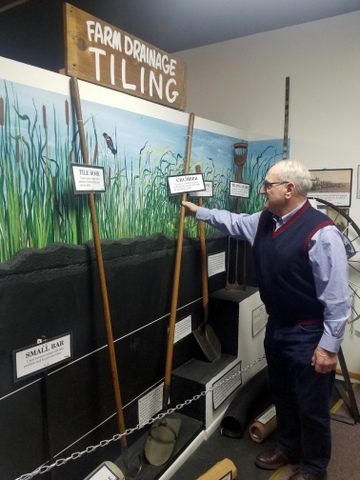

Jim Andrew revisits the exhibit designed by his father, James H. Andrew, a long-time Greene County farmer. This Farm Drainage Tiling exhibit is housed at the Greene County Historical Society’s museum in Jefferson, Iowa.

The region’s extensive swamps and sloughs were remnants of the last glacier, which loosened its icy grip on Iowa approximately 12,000 years ago. “There was a lot of water and nowhere for it to go,” Otto said. “Drainage ditches had to be dug and tile lines had to be laid before the sloughs and swamps of Iowa could be farmed. This started around 1880 and picked up speed in the early 1900s as drainage technology became more advanced.”

Ag leaders like Civil War veteran and pioneer farmer Jesse Allee, who settled in the Newell area in 1871, knew ag drainage would be essential to the development and prosperity of the region. “He was far-seeing with the unshakable belief in the future of the community’s farm land,” stated the 1969 Newell centennial history book on display at the Allee Mansion south of Newell. “Jesse worked hard educating the public to the necessity of proper drainage if this area was to be a leader in agriculture.”

Settlers in Greene County faced a similar situation. “By 1880, many landowners realized underground drainage tile was needed to remove the excess water,” wrote James H. Andrew, a long-time Greene County farmer who created the Farm Drainage Tiling exhibit at the Greene County Historical Society’s museum

in Jefferson before he passed away in 2014.

As more settlers moved into Iowa and demand for tile drainage grew, tile kilns and factories popped up across the state, Otto noted. Greene County, like many Iowa counties, had multiple firms manufacturing clay tile. These businesses used locally-sourced clay, including the Jefferson Cement Products Co., which was located just north of the Greene County Fairgrounds and operated until about 1930, and Lawton and Mass, which produced concrete tile at Cooper for a number of years, starting in 1895.

“There were also small machines made for farmers to mix concrete and scoop it into a manually-cranked device that used metal forms to make various sizes of tile,” wrote Andrew, who was known as “Mr. History.” “They advertised you could make your tile at home for half the cost of commercial tile. But it’s doubtful if this was very successful, since the proper steaming and curing of concrete tiles is important.”

Drainage districts take shape

Ag drainage in Iowa took a major leap forward in 1904, when state legislation provided for the formation of drainage districts. “Farmers could always drain their own lands if they wanted to, but to truly manage drained water meant cooperation with your neighbors,” Otto said.

A group of farmers could petition for a drainage district. An engineer would survey the land to establish the boundaries of the area, and a feasible drainage plan would be developed.

If approved, a contract would be drawn up, with the cost paid by assessing each landowner for his or her fair share, considering his needs and the acres involved. The county acted as the administrator of the drainage district and assessed taxes against the land, as needed, to pay for the initial cost and later for the maintenance of the drainage district. Many times, the money would be borrowed by issuing bonds, and the landowners would make payments on a 10-year plan, Andrew noted.

“The drainage district plan provided the larger tile needed for the main arteries of the system,” Andrew wrote. “Individual landowners were responsible for installing and paying for the lateral tile lines installed on their respective farms to complete the drainage plan.”

From 1904 to 1919, an average of 10 new drainage districts were created per year in Greene County. “That’s a new district about every five weeks,” Andrew wrote.

The 1910s became the golden age of ag drainage when most of Iowa’s public drainage systems were built, Otto added. “By 1912, Iowa’s farmers had spent more money on drainage then the U.S. government spent to build the Panama Canal.”

A Greene County drainage district created in 1916 to drain 998.7 acres using approximately 3.5 miles of tile ranging in size from 10 inches to 22 inches cost of $9,135, [more than $218,640 in today’s dollars], said Michelle Fields, drainage clerk for Greene County. “A drainage district created and installed in 2013 drained 865.5 acres using around 2.38 miles of tile ranging in size from 15 to 24 inches at a cost $532,500,” she added.

This unique clay ag drainage tile dated 1885 is on display in the Greene County Historical Society’s museum in Jefferson. The message carved around the exterior of the tile reads, “We the men who started the tile work did so with a motive to benefit the town and country. Signed T.P. LaRue of Scranton, Iowa.”

Recalling the life of a ditch digger

By 1920, the formation of ag drainage districts in Iowa slowed down as the post-World War 1 ag depression hit rural America. Still, the work continued.

“Steam power (and later gasoline) engines moved steel and iron machines that could move a lot more dirt around than could horse-drawn scrapers and plows,” Otto said.

Around 1923, after most Greene County drainage districts were in place, the first tiling machines started to be used, although hand digging continued for many years, Andrew noted. In the spring, summer and fall, men could find a job “in the ditch” if they wanted to work. “Many immigrants coming to the USA found their first jobs digging canals, and later drainage ditches. You didn’t have to know English to be a good man in the ditch,” added Andrew, who noted that many of these workers were from Sweden and Ireland.

The early tilers typically lived in tents or small, portable shacks next to the wet land they were draining. They often cooked their own meals and lived off the land by catching frogs for fried frogs’ legs and snapping turtles for turtle soup. They shot ducks, geese and rabbits for meat. Sometimes bullheads and other fish could be caught in the larger ponds, Andrew noted. For water, including drinking water, the men would take a post auger and dig a hole 3 to 4 feet deep and would set in an old farm pump.

“Ditch digging was well organized, and the men were paid by the rods of ditch dug by each man,” Andrew wrote. “No work—no pay. And of course, workmen’s compensation, health insurance and so on were unheard of.”

“Generous gifts”

By the 1970s, corrugated plastic pipe was introduced, which gradually phased out clay tile as the most efficient way to drain land. Today, Greene County has nearly 3,000 miles of drainage district tile and pipes, ranging from 4 inches to 48 inches in diameter. This distance would roughly equal a tile ditch spanning from New York to San Francisco.

“Note that the 3,000 miles is just a measure of the district tiles,” Fields said. “That number would be exponentially larger if you included private tile lines.”

As ag drainage issues have increasingly become intertwined with debates about conservation and water quality, it’s important to keep the line of communication open, Otto said.

“I think the harsh reaction against ag drainage that’s happened in the past few years is due in part to people suddenly wanting to engage in drainage matters, but unsure of what drainage is and does, who administers it and what powers they have. On the other side of the coin, the people trusted to manage the public’s interests in drainage have a responsibility to break down barriers, explain misconceptions and guide the conversation to a common ground.”

That’s a big reason why Andrew documented the history of ag tiling, counting it as one of the most important events in local history and the settlement of the region, noted his son, Jim Andrew of Jefferson.

“Think of the men and the effort it took to dig the clay, form and cure the tile, haul the tile to the jobsite, the survey crews working in ponds and swamps, the drainage plans made by the drainage engineer proving drainage was practical, the legal problems of objections and disputes, letting the bids, and, most important, the hundreds of men with strong backs who worked digging the ditches, laying the tile and filling the ditches,” wrote James H. Andrew.

“Yet, the tile is hidden underground, and the ‘Iron Men’ tilers are all deceased,” he concluded. “As time passes, there is little appreciation for the cooperative efforts that drained Greene County and made it so productive. Only when these old tile systems fail and have to be replaced at great expense will many people realize the generous gifts we’ve received from the drainage district system.”

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2019 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

Ag-Vocating Worldwide: Top 10 Tips for Sharing Ag’s Story with Consumers

Any of these sound familiar? Many consumers today don’t understand modern agriculture. Activists are spreading misinformation about farming. Myths about farming seem to carry more weight than facts. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. While these things are top of mind for me here in Iowa, they’re hot topics in Germany and across Europe, too.

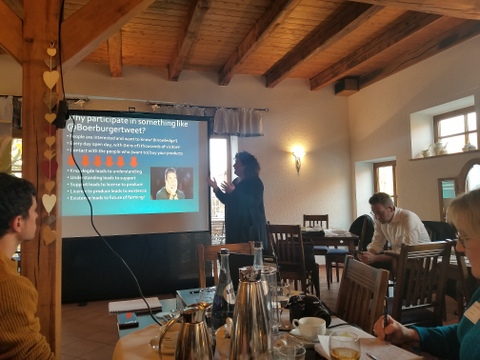

So what do you do about it? We shared best practices when I joined five other ag leaders from Iowa in northern Germany to meet with European farmers, veterinarians and other ag professionals during the Transatlantic Agricultural Dialogue on Consumer Engagement from November 11-16, 2018.

“This experience highlighted why we must make time to share the what and why of how we do things on the farm,” said my friend Chad Ingels, a farmer from Randalia, Iowa, who participated in the Germany study trip, which was supported by the German-American Chamber of Commerce. “Consumers around the world really have no idea what happens in the day-to-day activities on the farm. We need to share our story and keep it simple, without using ‘farmer jargon.’”

Learning practical tips in Germany for telling ag’s story effectively

Ingels, who raises corn, soybeans and hogs and is active on social media, appreciated the opportunity to exchange practical ideas to address the public’s questions about food production. During these discussions, ag leaders from both sides of the Atlantic shared their 10 top tips for engaging with consumers, including:

1. Be willing to engage. Who is telling agriculture’s story, and what are they saying? Don’t leave it to chance, said Caroline van der Plas from the Netherlands, who encourages farmers to build relationships and share their story with consumers, the media and lawmakers. “If you don’t share your story, others like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) will tell it for you,” said van der Plas, who coordinates the Dutch social media project @boerburgertweet, which allows farmers to share their story with consumers on Twitter.

The ripple effect from one story can be powerful, noted Janice Person, online engagement director for Bayer CropScience. She credits one interview more than 20 years ago with Louisiana farmer Ray Young for motivating her to pursue an agricultural communications career. “I was a city girl from Memphis who was interested in ecology,” said Person, keynote speaker at the Transatlantic Agricultural Dialogue on Consumer Engagement. “When I interviewed Ray Young, he had me so focused on his soils that I can still see them in my mind. He explained conservation tillage and helped me understand how he was getting it to work on his farm. By taking the time to tell his story, Ray helped me become an influencer for agriculture.”

2. Look at ag through consumers’ eyes. Empathy matters. People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care, Person said. “Many people today are hearing things about food and agriculture that scare them. Sometimes people are angry, sometimes they are confused and sometimes they want to listen.” Most people just want what’s best for their families, added Person, who noted that farmers can bring a valuable, real-world perspective to the conservation.

3. Tell a different side of the story. While most consumers have heard a lot about organic farming, they rarely hear about other types of production. “It’s easy for people to think there’s only one side of the story or one way to farm, unless you share a different perspective,” Person said.

4. Focus on the moveable middle. Activists are loud, but they are still a minority, said Nadine Henke, an ag-vocate from Germany. “There are still a lot of people in the middle, but few really understand modern agriculture. We can reach out to them.”

Farmer Derek from Kansas and his trombone, calling the cows

5. Find inspiring ag-vocates. There are many ag-vocates to follow online, from Dirt Sweat N Tears (@farmermegzz on Twitter), a film industry specialist turned farmer from Saskatchewan, Canada, to Derek Klingenberg (@Farmer Derek on Twitter), a Kansas farmer and rancher whose popular YouTube videos range from him playing his trombone to call his cows to a video of a college choir singing in his new grain bin. “We have different crops and livestock and various ways of farming, so our stories are all different,” Person said. “What ag-vocates have in common is their decision to tell their story and make a positive impact.”

6. Never underestimate face-to-face conversations. While social media gets a lot of attention, it’s not the only place to tell ag’s story, Person said. “Some of the most important conservations still take place in person.”

7. Show how technology can be part of the solution. “Most people like to be modern,” Person said. Share the story of modern ag by showing how technology is helping protect the environment with solutions like precision spraying. “People love to discover things,” Person said. “They don’t like to be lectured to. Sharing knowledge can create a sense of wonder.”

8. Stay on track. Challenge people and encourage them to think about a different viewpoint, but always be respectful of your audience, Person said. “Be careful about going on defense too soon. Also, make time to explain not just the how, but why you do what you do on the farm.” Don’t stop with posting pictures, she added. Share your stories of the land and what you think is special about your region. If you have livestock, explain the how and why of manure management. If you like to cook, showcase seasonal foods and recipes. In any case, don’t devote too much time to people who aren’t willing to listen and only want to argue, Caroline van der Plas added. “The longer you engage with activists, the less time you have to tell your story.”

9. Build trust. What’s the ultimate goal of telling ag’s story? Building trust. “It’s all relationship based, and trusted relationships are so important,” Person said.

10. Take the long view. Communication is never a once-and-done deal. It’s an ongoing process. “What can you do in the next year, and the next five years, to tell your ag story?” Person asked. Also, remember that you’re not alone. “Sometimes food and farming issues feel so polarized that it’s easy to forget other people are saying the same things we are,” Person said. “It’s incredibly rewarding to reach out with ag’s story. Know that there is power in coming together.”

So here I am back home in rural Iowa, trying to implement these 10 tips, starting with this article, which originally appeared in Farm News and the Fort Dodge Messenger. I’d love to hear from you, too. In your experience, what works well to share your story effectively?

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2018 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

Butter Sculptures to Christmas Ornaments: Waterloo Boy Tractor Celebrates 100 Years

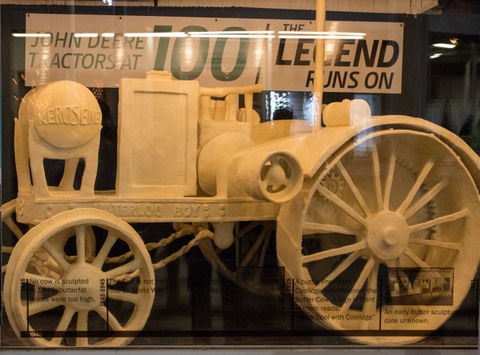

It’s hard to imagine a time when John Deere wasn’t a powerhouse in the tractor business. Yet, John Deere wouldn’t enter the farm tractor business until March 1918 through the acquisition of the Waterloo Gasoline Engine Company, and it’s a milestone that has been commemorated in everything from butter to Christmas ornaments.

Deere has featured a picture and story depicting the 100th anniversary of the iconic Waterloo Boy on its 2018 Christmas ornament. The 2018 Iowa State Fair also honored the tractor by featuring the world-famous Butter Cow beside a butter sculpture of the Waterloo Boy. Both butter masterpieces were displayed in the 114-year old John Deere Agriculture Building’s 40-degree cooler throughout the fair, which ran from August 9-19.

The Iowa State Fair has long been a prime venue to display Deere equipment in its various forms. A quote from the John Deere Sales Department in 1940 read, “I feel that the machinery and industrial exhibits for 1940 excelled any previous year’s display,” according to history shared by the Iowa State Fair. “We consider our Iowa State Fair exhibit to be a very beneficial part of our advertising program, and we will be with you again in 1941.’”

Waterloo Boy butter sculpture 2018 Iowa State Fair

Meeting the challenge of a reliable, durable tractor

Frequently ranked as one of the top events in the country, the Iowa State Fair is the single largest event in the state of Iowa and one of the oldest and largest agricultural expositions in the country and annually attracts more than a million people from all over the world.

In 2018, the Iowa State Fair used more than 50 John Deere tractors and utility vehicles provided by Van Wall Equipment. In addition, a 1919 Waterloo Boy model N tractor was on display in the Machinery Grounds at the Iowa State Fair.

To understand the significance of the Waterloo Boy, take a trip back in time, said Neil Dahlstrom, manager of the John Deere Archives and History. In the critical five-year stretch (1912-1917) prior to John Deere entering the tractor business, there were two key issues the company needed answered.

“First, what did farmers really want from a machine that would soon make the horse obsolete?” said Dahlstrom, who noted that salesmen, territory and branch managers, and Deere’s top leadership scoured the country to understand what customers desired.

Also, how could the equipment to be manufactured to be durable enough to stand up to daily farm use?

Deere had considered every imaginable idea. The company had developed one-, two- and four-cylinder concept tractors. Some ran on gasoline. Others ran on kerosene. Some had all-wheel drive. Others had front-wheel drive. The company even explored concepts like line steering, which was meant to replicate horse reins as the steering mechanism to ease farmers into power farming, Dahlstrom said.

A motorized cultivator, what Deere called a “Tractivator,” was brought to market by several competitors, but Deere determined it did not provide any cost savings compared to horses.

The challenge of producing a durable tractor loomed large. In a letter to company president William Butterworth in 1915, Deere’s superintendent of factories George Mixter noted that tractors offered by competitors up to that point “have not been built with the proper spirit behind the design and manufacture to insure their durability in the hands of the farmers.” But if Deere could “build a small tractor that will really stand up for five or more years’ work on the farm, I believe they will be a permanent requirement of the American farmer,” Mixter wrote.

Deere ultimately found the solution with the Waterloo Boy tractor and acquired the Waterloo Gasoline Engine Company in Waterloo, Iowa, on March 14, 1918. Although anxious to start selling the Waterloo Boy, Deere dealers had to wait while Deere honored existing contracts, which did not expire until Dec. 31, 1918, Dahlstrom said.

Visitors snapped photos of the iconic Waterloo Boy butter sculpture 2018 Iowa State Fair.

Waterloo Boy makes its debut

Deere put its money where its instincts were. Over the next year, the company spent more than one-third of its advertising budget touting the Waterloo Boy tractor, Dahlstrom said.

Specifically, Deere invested $50,000 on tractor advertising in the year following its debut of the Waterloo Boy—approximately $747,000 in today’s money. Another way to get the company’s new product out in front of customers was to take it on the road – literally.

The National Tractor Demonstrations started to become more mainstream after being introduced in the United States in 1913. An eight-city, eight-week tour schedule was the perfect opportunity to unveil Deere’s Waterloo Boy, Dahlstrom said. Salina, Kansas, served as the ideal backdrop in August 1918, since this was the nation’s largest demonstration.

Deere had participated in tractor demonstrations since the original Winnipeg Agricultural Motor Competitions in Manitoba, Canada, in 1908 – but not with a tractor. Instead, Deere had paired its plows with leading tractor manufacturers. That changed now that the Waterloo Boy was part of the Deere family.

At Salina, Deere spared no expense, showcasing 12 Waterloo Boy tractors as the centerpiece of a display that included John Deere signs, Waterloo Boy signs and a copper leaping deer statue, Dahlstrom said. “There were two stars during this week of 100-degree days – ‘ice water on tap’ and the Waterloo Boy Model ‘N’ tractor,” he added.

The Model “N” demonstrated its merits by pulling tractor plows, disc harrows and grain drills. Visitors were shuttled in three John Deere farm wagons pulled by Waterloo Boy tractors. By all accounts, the debut was a success.

“The award for the most elaborate, largest and most artistic exhibit tent at the Salina tractor show will undoubtedly go to the John Deere Plow company of Kansas City,” wrote the editors of a Kansas City newspaper.

As Deere’s advertising campaign swung into full gear, the Waterloo Boy tractor was promoted as the “best and most efficient tractor” on the market for farmers inclined to buy a tractor. By October 1918, readers of Deere’s magazine, The Furrow, saw an advertisement for the line of Waterloo Boy tractors and stationary engines. The ad guaranteed the Waterloo Boy’s “ample power for field and belt work.”

Waterloo Boy butter sculpture 2018 Iowa State Fair

In January 1919, with tractors now available through John Deere dealers, Deere’s first print ad for the trade press appeared in The Farm Implement News. It featured two areas of emphasis: “A Good Tractor Backed by a Permanent Organization.”

After years of development, John Deere customers and John Deere dealers finally had their John Deere tractor.

“It took longer than the company expected, but a determination to do it right instead of doing it fast now brought the John Deere tractor to market,” Dahlstrom said.

As a result, customers got “the assurance of more tractor work per dollar of fuel cost; longer tractor life with less repair cost; accessibility of parts that makes caring for the tractor simple and easy; and dependable power for all farm work.”

The tractor era had officially arrived.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2018 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

Barn Helped Inspire Master Craftsman to Create Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

When a sow kicked a heat lamp into the straw one cold January night in 1954 and burned down the barn on the Carroll County farm where Lynn Dobson’s family lived, no one imagined how much impact the blaze would have. It became a defining moment for Dobson, however, even though he was only four years old at the time.

“When the barn was rebuilt that summer, I wanted to be out working with the carpenters all the time,” said Dobson, founder of Dobson Pipe Organ Builders Ltd. of Lake City, which constructs fine pipe organs for churches, universities and other clients. “The carpenters told my mom they didn’t mind, and they even gave me small tools to ‘work’ with, including a hammer and screwdriver.”

Once the Wilson brothers from Farnhamville completed the new barn, they were hired each summer to work on other construction and remodeling jobs for various outbuildings at the Jasper Township farm. “These construction projects were a highlight of growing up on the farm,” said Dobson, who also learned carpentry skills from his father, Elmer, who was a cabinetmaker as well as a farmer. “My imagination was fired up.”

“They feel like cathedrals”

Dobson admits he enjoyed building things much more than farming. That didn’t mean he didn’t have his share of chores to do on the farm, however. His father liked raising livestock, so there were usually eight to 10 milk cows to care for, along with feeder calves, hogs and chickens. In fact, the barn was built for milk cows, said Dobson, who noted that Bill Troxel from Lanesboro picked up milk from the farm.

Lynn Dobson designs grand pipe organs that grace churches in small towns like Lake City, Iowa, to cathedrals in New York City.

The barn also housed stock cattle. Dobson will never forget the little bull calf that had to be bucket fed after its mother died. “He had always been so gentle, but one night he decided to pin me against the barn. His horns pushed into the wall and his head was right against me. I never had to feed him again after that.”

Other activities inside the barn were much less threatening. Dobson enjoyed playing in the barn with his sisters and building forts in the straw bales. Sometimes he climbed the ladder that extended to the peak of the roof. “I’d catch little pigeons and try to tame them and raise them as pets,” he said.

The barn was always a hub of activity, Dobson added. While Elmer Dobson phased out of the dairy business in the early 1960s, he continued raising hogs and farrowed sows in the barn. He maintained his livestock operation for many years until he and his wife, Muriel, retired and moved to Lake City in the early 1980s.

After Dobson graduated from Glidden High School in 1967, he studied art at Wayne State College in Nebraska, where he earned his undergraduate degree in 1971. In 1974, he established Dobson Pipe Organ Builders, which recently designed, built and installed a customized pipe organ for the 2014 observance of the 750th anniversary of the founding of Merton College at Oxford, the oldest university in the English-speaking world.

In a way, the inspiration to create this massive organ, known as Opus 91, can be traced to the Carroll County barn that captured Dobson’s interest as a boy. “Barns are grand buildings, and I’m inspired by their magnificent spaces,” he said. “They feel like cathedrals inside.”

Pipe organ builder hits a high note

Note from Darcy: I wrote this feature below on Dobson Pipe Organ builders in 2013.

Donald Hobbs, a long-time employee at Dobson Pipe Organ Builders in Lake City, helps create the masterpieces that the company builds for clients worldwide.

A former John Deere shop has housed Dobson PIpe Organ Builders for years in Lake City, Iowa.

The journey that started on a farm near Lake City has taken an Iowa pipe-organ company international, thanks to the creative vision and entrepreneurial skills of Lynn Dobson.

Dobson Pipe Organ Builders Ltd. designed, built and installed a customized pipe organ for the 2014 observance of the 750th anniversary of the founding of Merton College at Oxford, the oldest university in the English-speaking world. “It’s very unusual for American organ builders to send organs to Europe,” said Dobson, who noted that construction on the organ started in 2011. “It hardly ever happens.”

Made of quarter-sawn white oak from the southern United States, this masterpiece (known as Opus 91) rises 46 feet tall, stretches 26 feet wide, weighs about 16 tons and features hand-carved designs. It also contains nearly 3,000 pipes, which range in size from a drinking straw to a telephone pole.

Opus 91 is a 52-rank mechanical key action organ, which means that there are mechanical links that directly connect each of the keys to valves under the pipes. This kind of organ was created before the advent of electricity and generally is preferred among premier organists.

While this is Dobson Organ’s first overseas project, the company had built 90 organs since 1974 before creating “Opus 91” for Merton College. “We’ve never built the same organ twice,” said Dobson, the company’s president and artistic director.

Organ building, like many centuries-old crafts, is becoming increasingly rare. Companies like Dobson’s are even fewer, with an estimated half dozen nationwide. As I look back at the last 40 years of my life, organ building was a good career for me. It gave me a chance to be creative and work with many creative people over the years. I’ve also had the chance to travel and see and do an almost unimaginable variety of things that I realize have made my life a very satisfying one. Dobson grew up on a farm south of Lake City, where he learned about woodworking from his father, a skilled carpenter and cabinetmaker. While attending Nebraska’s Wayne State College, studying art and industrial education, Dobson tinkered with an old, non-working pipe organ in the college administration building. By the time he left, it was playable.

Organ building, like many centuries-old crafts, is becoming increasingly rare. Companies like Dobson’s are even fewer, with an estimated half dozen nationwide. As I look back at the last 40 years of my life, organ building was a good career for me. It gave me a chance to be creative and work with many creative people over the years. I’ve also had the chance to travel and see and do an almost unimaginable variety of things that I realize have made my life a very satisfying one. Dobson grew up on a farm south of Lake City, where he learned about woodworking from his father, a skilled carpenter and cabinetmaker. While attending Nebraska’s Wayne State College, studying art and industrial education, Dobson tinkered with an old, non-working pipe organ in the college administration building. By the time he left, it was playable.

This inspired him to start his own company, which started as a two-man operation and has grown to include 19 skilled employees. They include voicers, pipe makers, cabinetmakers and general organ builders who work in a 1890s-vintage shop located on Lake City’s city square. The company has built about 20 new organs for customers in Iowa, including the Lake City Union Church, Westminster Presbyterian Church in Des Moines and the First Reformed Church in Orange City. The firm has restored an additional 20 organs across Iowa.

Dobson’s reputation has also earned the company acclaim across the United States. Some of the company’s largest projects include the organs at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles, the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia and St Thomas’ Church, New York City.

“I think every day is more exciting,” Dobson said. Even though the economy and a changing cultural and religious climate are great challenges for us in the organ building field the fact is we’re still able to be creative and work with good people. What could be better than that?

Dobson organ pipes can be as tiny as a pencil to produce the higher notes, and up to 40 feet tall (with pipes weighing 500 pounds) to produce the low notes. Pipes can be made of metal or wood. As shown here, the pipes’ coating, which keeps the solder on the seams, is washed off to expose the shiny pipes once the process is complete.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2018 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

Pieced Together: Barn Quilt Documentary Features Iowa Stories

Barn quilts have become a folk-art phenomenon in Iowa in the past 15 years, turning up not only on barns, but mailboxes, gardens, buildings in town and more. But there was a time not that long ago when no one had ever heard of a barn quilt—not until Donna Sue Groves wanted to add a little color to her corner of the world.

Her story—and those of barn quilt enthusiasts in places like Sac County—inspired the 53-minute documentary “Pieced Together,” which filmmaker Julianne Donofrio showed in Sac City to a full house at the First Christian Church on the evening of Sept. 24, 2018.

“A lot of people don’t know where barn quilts came from,” said Donofrio, who is from the New York City/Washington, D.C. area. “I want people to know Donna Sue’s story.”

The story, which includes many barn quilts across Iowa, began in 1989 when Groves’ family bought a farm in Adams County, Ohio, near the Ohio River Valley at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Groves made a casual remark to her mother, Nina Maxine Groves, about an uninspiring, time-worn tobacco barn on the farm.

“It was the ugliest barn I’d ever seen,” Groves said in “Pieced Together.” “I joked to my mother, ‘I’ll paint you a quilt square on it someday.’”

Game inspires a lifelong love of barns

Groves’ interest in barns dates back to her childhood. When her family would visit Groves’ grandmother in Roane County, West Virginia, Groves’ mother invented a car game to keep Groves and her brother quiet.

“You couldn’t play the typical license plate game when you’re traveling the back roads of West Virginia, because all you saw were West Virginia license plates,” Groves said. “Mother created a car game where we counted barns.”

Some barns were worth two points, while others were worth three points. If a barn had outdoor advertising, like “Chew Mail Pouch” or “RC Cola,” players got a 10-point bonus if they could read the lettering. Red barns also earned higher points. The chance to earn even more points awaited when the family’s wider travels took them past Pennsylvania Dutch barns with colorful, geometric hex signs.

The game led to discussions and questions about the barns, such as who built the barns, and for what purpose. Groves enjoyed these conversational teaching moments. “I looked forward to seeing barns,” she said.

Sac County Iowa barn quilt

Creating a clothesline of quilts across America

This history eventually inspired Groves’ involvement with the first barn quilt square, an Ohio Star pattern, which was created in October 2001 and displayed in Adams County, Ohio. This small gesture triggered a ripple effect across North America.

“If we didn’t pick up on this idea, someone else would,” said Groves’ mother, Maxine, who was featured in “Pieced Together.”

As more people wanted to create barn quilts, Groves and her fellow volunteers quickly learned that painting barn quilts directly onto barns didn’t work too well, but painted plywood squares offered a much better option.

Why stop with just a few barn quilts, though? “A trail of barn quilts could bring tourists here to see all the wonderful things Adams County offers,” noted Groves, who has served as a field representative for the Ohio Arts Council. “Then they’d stay in our bed-and-breakfasts and motels and eat at our restaurants.”

These opportunities for economic development, combined with the visual appeal of barn quilts, soon inspired a “clothesline of quilts” across America. Residents of an adjoining county, Brown County, Ohio, loved Groves’ idea and asked how to get involved. Folks in Tennessee read an article about the Ohio barn quilt project, called Groves and wanted to know how to do a similar project in their area. Grundy County, Iowa, also got involved in 2003, followed by Sac County.

When Sue Peyton and her family from rural Sac City heard about barn quilts, it seemed like a good fit for her son, Kevin, who was in high school and looking for a project he could use as a 4-H leadership project and a Herbert Hoover Uncommon Student Award project.

“I immediately fell in love with the project when I heard about it,” Sue Peyton said. “Barns and barn quilts are such a natural fit.”

The Peytons coordinated the construction and painting of Sac County’s first barn quilts in the summer of 2005. While some people weren’t quite sure what to make of the new barn quilts that started appearing on barns and corncribs around the county, the concept caught on quickly. “We hoped to get 20 barn quilts,” said Sue Peyton, who added that Sac County boasted 55 barn quilts within two years of the start of the project.

“I’ve seen a lot of quilt trails, and you embraced this early on and have done a tremendous job,” said Donofrio as she chatted with audience members in Sac City following her documentary.

Sac County barn quilt proponents Kevin Peyton and his mother, Sue, (center) welcomed filmmaker Julianne Donofrio, who showed her 53-minute documentary “Pieced Together” in Sac City to a full house at the First Christian Church in September 2018.

“We’re here to stay”

Anywhere there’s a barn quilt trail, every square tells a story. Also, there’s no right or wrong way to create a barn quilt. “Barn quilts have a storied history as complex and diverse as the quilt patterns themselves,” Kevin Peyton said.

Consider the Double Aster barn quilt pattern on the Hogue family’s 1943 barn north of Odebolt. The pastel-colored design complements the family’s Prairie Pedlar Gardens business. Owner Jane Hogue, who served on the original Sac County Barn Quilt Committee, enjoyed watching the “Pieced Together” documentary.

“It was fun to see the snippets of Sac County’s barn quilts in the film,” she said. “We’re proud to be part of Sac County’s barn quilt project. With our gardens and tourism, it’s a win-win.”

Sac County proves that barn quilts offer an effective way to help save barns, promote rural tourism and boost economic development, Sue Peyton added. She cited the vintage barn at the Rustic River Winery and Vineyard north of Lake View, for example. It has been remodeled not only into a winery, but a venue where people can host parties and other gatherings.

As the history of the barn quilt phenomenon is preserved through projects like “Pieced Together,” barn quilts are being praised as one of the greatest community art projects ever created. While there are barn quilt trails in 42 states, there is no national barn quilt organization, by design. Creating barn quilts at the local allows local people to make their mark, share their history and establish a legacy. “It’s so adaptable—that’s the beauty of it,” Groves said.

Above all, barn quilts inspire people to view rural communities in a new way. “Barn quilts prompt a question that starts a discussion,” noted a speaker in the “Pieced Together” documentary. “It’s a statement that, ‘We’re here, and we’re here to stay.’”

Barn quilts also prove the power of one person from an isolated rural county to inspire a vision that has touched an entire nation. “As times get harder, we forget how to dream,” said Groves, a cancer survivor. “I like to think the barn quilt trails allow people to dream.”

Sac County barn quilt near Early, Iowa

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2018 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

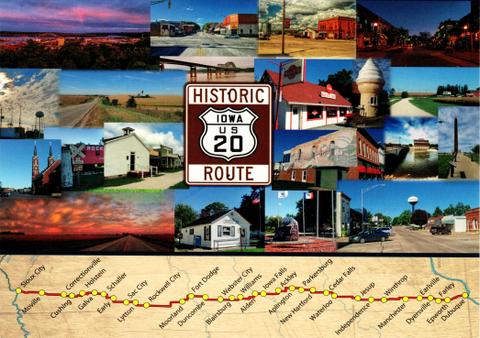

It’s Time to Be 20 Again: Take a Road Trip on Historic Highway 20

It’s a quest that’s decades in the making. When hundreds of people gathered in Holstein on October 19, 2018, for a ribbon-cutting celebrating the completion of U.S. Highway 20 as a four-lane thoroughfare across Iowa, the focus on the future was intertwined with the history of this remarkable road–which offers the perfect route for a road trip.

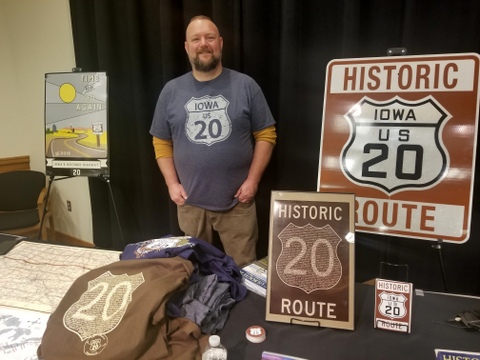

“Highway 20 is the longest highway in America, spanning 3,365 miles from Boston, Massachusetts, to Newport, Oregon,” said Bryan Farr, founder and president of non-profit Historic US Route 20 Association, which promotes travel along the original 1926 alignment of US Route 20. “Modern travelers aren’t always aware of Highway 20. We want to make it a tourist destination like Route 66.”

Highway 20 passes through 12 states, including Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho and Oregon. “A lot of interesting things have happened along the highway, from Puritan New England to the Wild West,” said Farr, who shared stories of history, presidents, natural wonders, quirky roadside attractions and more connected to Highway 20 during his program “Historic U.S. Route 20: A Journey Across America’s Longest Highway” on Oct. 14 to a large crowd at the Sioux City Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center.

But first things first—is 20 a highway or a route?

“It depends on where you’re from,” said Farr, who grew up in the Finger Lakes region of New York state and now lives in Chester, Massachusetts. “If you’re from Massachusetts, New York or Pennsylvania, you pronounce it ‘Root’ 20. If you’re from Ohio, Indiana or Illinois you say, ‘Route 20.’ If you’re west of the Mississippi River, it’s Highway 20.”

Bryan Farr is the founder and president of non-profit Historic US Route 20 Association, which promotes travel along the original 1926 alignment of US Route 20.

History happened here

The remarkable history of Highway 20 started with the passing of the Federal Highway Act of 1921, which appropriated $75 million for road construction throughout the country. The roads that would become Highway 20 were officially designated during the summer of 1925, with the original alignment of the highway taking shape in 1926.

Creating the modern, efficient, paved, four-lane highway travelers enjoy across Iowa today, however, took decades to create, Farr said. The road was often re-aligned throughout its history, and much of it was gravel for part of the highway’s history. “There are still little sections of the 1926 alignment of Highway 20 outside of Early and Fort Dodge that still are gravel,” Farr noted.

Speaking of Fort Dodge, this Highway 20 city has an unforgettable connection to Cardiff, New York, another Highway 20 town where one of the greatest hoaxes of the nineteenth century took place.

It all started when Stubb Newell of Cardiff, New York, needed a new well. On Oct. 16, 1869, Newell directed two well diggers to a spot he selected behind his barn. The men dug 3 feet and hit something solid. They uncovered a huge stone foot. As they dug more, an entire body of a man emerged. Two days later, a large tent was placed over the 10-foot stone man and crowds of nearly 200 to 500 people a day paid 50 cents to see this giant. Scientists, philosophers and the clergy attended and were challenged in their beliefs, noted the Historic US Route 20 Association website.

Legendary showman P.T. Barnum offered $60,000 for the giant but was turned down. Soon, however, the hoax came to light when people recalled a man named George Hull (a cousin of Newell) had visited a gypsum mine at Fort Dodge in 1868. He commissioned a 5-ton block to be used to carve a statue of Abraham Lincoln. The block of gypsum was shipped to Chicago and carved into this giant man. The carving’s surface was treated with acids and picked at with needles to give it an antiquated look. It was then shipped and buried in New York.

Today, the giant rests at the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, New York. In 1969, a replica was created from the same gypsum quarry and is on display at the Fort Museum in Fort Dodge.

These types of stories offer a unique perspective of Highway 20, which Farr has traveled from coast to coast. “I want to bring people back into small town America, to shop locally and support local businesses to boost economic development in communities that may be bypassed by interstate highways or other more popular routes.”

Gaining a new perspective of Highway 20

Highway 20 is also distinguished by a number of other noteworthy distinctions, including:

• Ties to some of America’s major and mid-sized cities. Highway 20 includes Boston, Buffalo, Cleveland, Chicago and Boise.

• A connection to five presidents. “Highway 20 is a presidential route,” said Farr, citing George Washington as well as Abraham Lincoln, whose famous debates with political rival Stephen Douglas took place in Freeport, Illinois. Highway 20 is also connected Galena, Illinois, where President Ulysses S. Grant had a home. In northern Ohio, Highway 20 passes through Freemont, home of President Rutherford B. Hayes, who served from 1877 to 1881, oversaw the end of Reconstruction and attempted to reconcile the divisions left from the Civil War. Cleveland, Ohio, honors President James Garfield, who was elected president in 1881 but whose service was cut short after 200 days in office when he was assassinated and later died on September 19, 1881.

• The women’s movement organized along the future Highway 20. The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women’s rights convention in the United States. Held in July 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, the meeting launched the women’s suffrage movement, which more than seven decades later ensured women the right to vote.

• Highway 20 name is more than just name. In 1925, a system of numbered highways debuted in America to replace the jumbled, confusing mess of named auto trails. “Routes with a zero at the end, like Route 20, were transcontinental routes,” said Farr, author of the book “Historic Route 20: A Journey Across America’s Longest Highway.” “Also, east-west routes have even numbers, while north-south routes have odd numbers.”

• Iowa attractions abound along Highway 20. Spanning roughly 330 miles across Iowa from Dubuque to Sioux City, Highway 20 offers plenty to see and do, Farr said. A few options include Dyersville, home of the famous Field of Dreams movie site, the National Farm Toy Museum and the Basilica of St. Francis Xavier; Independence, home of the Heartland Acres Agribition Center, which connects visitors to the past, present and future of Iowa agriculture; Sac County, with its famous barn quilt trail and world’s largest popcorn ball in Sac City and Sioux City, with its rich history related to the journey of the Lewis and Clark expedition nearly 250 years ago.

While the first Historic Route 20 sign was placed in Painesville, Ohio, in 2014, Cushing became the first Iowa community to display one of the distinctive signs. This sign greets visitors as they enter the small Woodbury County town from the east on the old route of Highway 20.

It’s interesting to note that bypasses started being built along Highway 20 almost from the start, starting in Massachusetts in the late 1920s. By the 1950s, bypasses in Iowa rerouted Highway 20 out of Farley in eastern Iowa. The trend hasn’t stopped since then. In recent years, communities along historic Highway 20 have been installing signs to denote their unique place along the route. While the first Historic Route 20 sign was placed in Painesville, Ohio, in 2014, Cushing became the first Iowa community to display one of the distinctive signs. This sign greets visitors as they enter the small Woodbury County town from the east on the old route of Highway 20.

While efficient transportation has its place, Farr encourages travelers venture off the interstates and four-lane Highway 20, explore the nearby towns and rural areas and see some the best of America. “Highway 20 is like a companion,” said Farr, who is promoting the new slogan “It’s time to be 20 again.” “This road will take you home.”

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

@Copyright 2018 Darcy Maulsby & Co. Blog posts may only be reprinted with permission from Darcy Maulsby.

DNA Helps Sailor Killed at Pearl Harbor Return to His Family

It was the telegram no family wanted to receive. “The Navy Department deeply regrets to inform you that your son Bernard Vincent Doyle, seaman second class, U.S. Navy, is missing following action in the performance of his duty and in service of his country.”

The telegram, dated December 20, 1941, was sent to Doyle’s father, John. Weeks later it was confirmed that Bernard “Barney” Doyle, a 19-year-old from Red Cloud, Nebraska, had been killed in action while serving on the battleship USS Oklahoma during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

The loss still lingers. “My brother was the most caring person I knew,” said Fran Nutter, 94, Doyle’s younger sister who has lived in Lake City since 1947. “He was always happy, and everyone liked him.”

Bernard Doyle, sailor, USS Oklahoma, killed in action at Pearl Harbor

Doyle was buried with full military honors at the Lake City Cemetery around noon on October 13, 2018, following a Mass of the Christian burial at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Lake City at 11 a.m. High-ranking members of the U.S. Navy attended the services, which were open to the public.

While Doyle’s remains had been classified as non-recoverable, a new chapter in his story is being written, thanks to advances in DNA technology that allowed his remains to be identified and returned to his family. Gov. Kim Reynolds ordered that all flags in Iowa fly at half-staff from sunrise to sunset on October 13 to honor Doyle.

All this support is comforting to Nutter and her family. “I always kept Bernard’s picture on display in my home,” she said. “My family thinks he’s a hero.”

Service and sacrifice

Bernard Doyle was born in Esbon, Kansas, on January 17, 1922, and grew up on a farm with his six brothers and sisters. The family lived in south-central Nebraska, not far from where their grandfather John Doyle homesteaded in Kansas, said Nutter, who remembers the hardships of the Great Depression. “Those were the days when Dad put molasses on tumbleweeds for the cattle to eat.”

After graduating from Red Cloud High School in 1940, Bernard Doyle enlisted in the U.S. Navy on May 28, 1940, in Omaha. He was later assigned to the USS Oklahoma, which was part of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

The USS Oklahoma arrived in Pearl Harbor on December 6, 1940, one year and one day before to the fateful attack. The USS Oklahoma was on Battleship Row on the morning of December 7, 1941, when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor. The Japanese used dive–bombers, fighter–bombers and torpedo planes to sink nine ships, including five battleships.

The crew of the USS Oklahoma did everything they could to fight back, according to the official website of the USS Oklahoma. In the first 10 minutes of the battle, though, eight torpedoes hit the USS Oklahoma, and she began to capsize. A ninth torpedo hit her as she sunk in the mud.

More than 2,400 Americans died during the Pearl Harbor attacks, including 429 men on the USS Oklahoma. In the aftermath of the tragedy, however, families back home didn’t know if their loved ones had survived or perished.

“After I heard the news, I had a feeling my brother would be okay,” said Nutter, who was working at an ammunition depot in Denver, Colorado, at the time. “I had no idea how serious things really were.”