Busting the Iowa Butter Gang

“Hey, did you ever hear of the Iowa Butter Gang?” It’s the last question I expected to hear during my recent “Culinary History of Iowa” book signing in West Des Moines, and it definitely caught my attention.

It came from Jan Kaiser, a former Des Moines librarian who had first “encountered” the nefarious gang a few years ago through research into 70+-year old newspaper archives.

Turns out that crime came in many forms during the Great Depression. Back then, butter was big business in rural Iowa. Not only was Iowa a leading dairy state, but hundreds of Iowa creameries produced high-quality butter that helped make Iowa a top shipper of butter into the New York City area, I learned recently from Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Bill Northey.

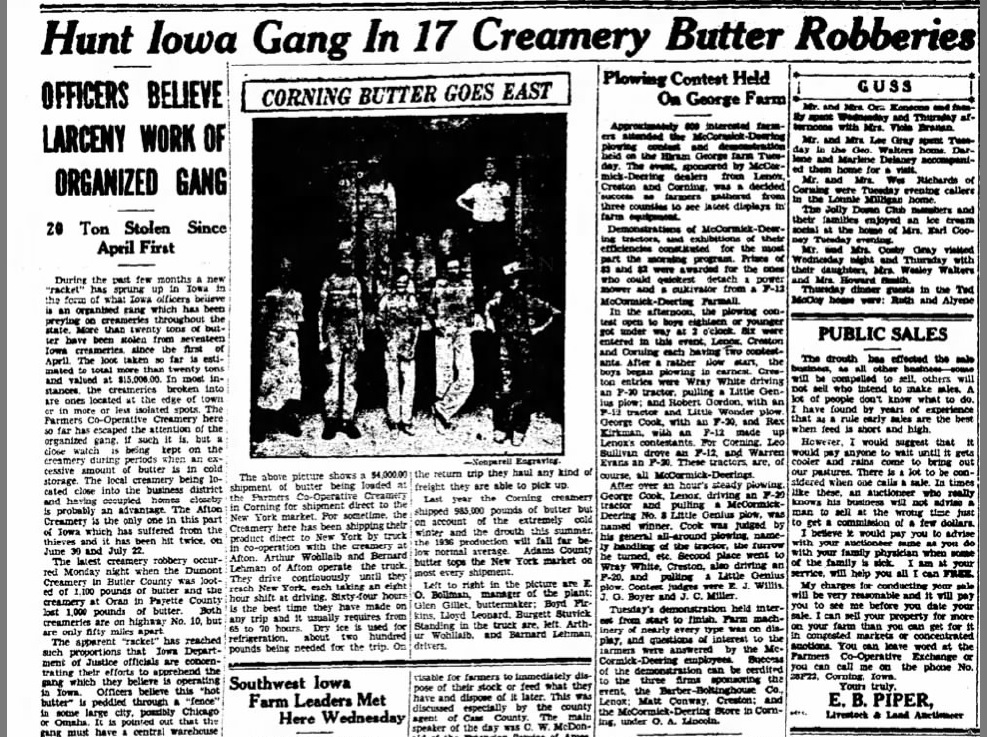

While some Depression-era criminals robbed banks, some thieves in rural Iowa opted to rob creameries. A headline in the Aug. 6, 1936, edition of the Adams County Free Press newspaper announced, “Hunt for Iowa Gang in 17 Iowa Creamery Butter Robberies: Officers Believe Larceny Work of Organized Gang.”

The article noted that during the spring and summer of 1936, a new “racket” had sprung up in Iowa in the form of an organized gang that preyed on creameries throughout the state. By early August 1936, more than 20 tons of butter had been stolen from 17 Iowa creameries since early April 1936. “The loot taken so far is estimated to total more than 20 tons and is valued at $15,000,” noted the news article.

In most cases, the creameries that were broken into were located on the edge of town or in isolated spots. The gang’s targets in 1936 included:

• April 3, Palmer, 2,172 pounds

• April 8, Fenton, 3,440 pounds

• May 15, Fenton, 2,080 pounds

• May 28, Edgewood, 630 pounds

• June 4, Britt, 5,184 pounds

• June 12, Kimballton, 4,000 pounds

• June 20, Coulter, 4,095 pounds

• June 30, Afton, 2,200 pounds

• July 1, Hampton, 2,209 pounds

• July 3, Hubbard, 7,488 pounds

• July 8, Palmer, 3,553 pounds

• July 11, Randall, 2,304 pounds

• July 22, Afton, 2,764 pounds

• July 30, Nashua, 1,500 pounds

• July 31, Masonville, 2,228 pounds

• August 3, Dumont, 1,100 pounds

• August 3, Oran, 1,000 pounds

“It is believed that before each burglary, the creamery is selected by the gang and careful plans made,” stated the Adams County Free Press. “The robbers are evidently expert burglars and experience little difficulty in breaking into creameries. They use a truck and are gone with their loot before local officials know there has been a burglary.”

Butter making was big business in small-town creameries across Iowa in the 1930s, including this creamery in Somers (featured in my Calhoun County book). George Smith built Somers’ first creamery was built in 1900. In 1913 S. P. Petersen purchased and updated the creamery, which became a major business in town for many years. The round tubs in this photo each held 65 pounds of butter. This butter was sold to area stores. In Fort Dodge alone, about 2 tons of butter was sold each week. Butter from Somers was also sent to New York.

Peddling “hot butter”

The writer speculated that the gang must have a central warehouse, since butter is highly perishable. The apparent racket reached such epic proportions that Iowa Department of Justice officials concentrated their efforts to apprehend the gang. “Officers believe this ‘hot butter’ is peddled through a ‘fence’ in some large city, possibly Chicago or Omaha,” the writer noted.

(A fence is someone who knowingly buys stolen property for later resale, sometimes in a legitimate market. The fence acts as a middleman between thieves and the eventual buyers of stolen goods who may not be aware that the goods are stolen.)

The article continued, “The Farmers Co-operative Creamery here [in Corning] so far has escaped the attention of the organized gang, but a close watch is being kept on the creamery during periods when an excessive amount of butter is in cold storage.”

It’s no wonder locals were keeping a close watch. The Farmers Co-op Creamery shipped thousands of dollars of butter each year to the New York market. The Adams County Free Press reported that two local truck drivers would each take eight-hour driving shifts and drive straight through from Iowa to New York. The best time they made from Iowa to New York was 64 hours, although the trip usually took 65 to 70 hours.

About 200 pounds of dry ice were used for refrigeration during the trip. On the return trip, the drivers hauled any kind of freight they were able to pick up. In 1935, the Corning creamery shipped 985,000 pounds of butter, noted the newspaper article. Due to the harsh winter and summer drought of 1936, however, that year’s production was expected to fall far below average—a fact that made the butter robberies of 1936 even more devastating in rural Iowa.

Finally—a big break in the case

By August 1936, officers with the Iowa State Patrol (formed just a year earlier in 1935) and a group of northern Iowa vigilantes and deputy sheriffs had been driving the secondary and dirt roads nightly for the last two months, trying to catch the butter gang, according to the Des Moines Tribune (the capital city’s afternoon newspaper that ended in 1982).

Some promising leads ended in disappointment. In the summer of 1936, officers arrested Harvey Mighell of Holstein on suspicion that he was connected with the butter gang. He was taken to Audubon, where he was questioned and later released under $2,000 bond. Mighell denied having anything to do with the Iowa butter thefts.

Law enforcement officials got a big break, however, by late August 1936. A headline in the Aug. 29, 1936, edition of the Des Moines Tribune proclaimed “Iowa Butter Gang Crushed.”

Turns out an Omaha gang of six men and one woman stole some $30,000 worth of butter, cheese and eggs in a string of more than 30 robberies across Iowa in 1936. (The pilfered dairy products were worth nearly $525,000 in today’s money.) The butter was trucked to Omaha and was sold through a fence.

“Virtually every sheriff in northern Iowa has been on the case as well as several detectives of the Omaha police department and other Iowa town police departments,” the reporter noted.

Iowa prosecutors charged the gang with 32 robberies. Detectives recovered 70 tubs of butter, the Tribune reported, 66 of which had been stolen from a creamery in Wesley. All the cheese was lifted from Ionia, the story reported. Law enforcement officials took the dairy products and sold them through legitimate channels to packers in Omaha.

“Capture of the Butter Gang was the climax of one of the greatest Iowa manhunts in recent years,” officials told the newspaper.

One more try?

The story wasn’t over, though. Less than five years later, one of the original butter gang members tried to revive the scheme. Under the headline “Butter Theft Gang Thwarted,” the Jan. 15, 1941, issue of the Mason City Globe-Gazette reported the arrest of Bryon Green, 32, of Sioux City. “R.W. Nebergall, chief of the Iowa Bureau of Investigation, believed that Green was attempting to set up a new ‘butter theft gang’ in Iowa,” stated the article.

On Dec. 13, 1940, Green had been released from prison in Stillwater, Minnesota, after serving three and a half years for burglary. Within a few weeks of his release from prison, Green was arrested by Chicago police, who accused him of entering the Masonville, Iowa, creamery on January 9, 1941, and shipping 1,230 pounds of stolen butter to a Chicago firm.

Thus ended the saga of the infamous butter gangs that terrorized rural Iowa in the 1930s. Their nearly forgotten story faded into history, along with the small-town creameries that once inspired their notorious crime spree.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you want more more intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, recipes and tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Feel free to share this information with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press, as well as my Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing, which showcases the history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

About me:

Some people know me as Darcy Dougherty Maulsby, while others call me Yettergirl. I grew up on a Century Farm between Lake City and Yetter and am proud to call Calhoun County, Iowa, home. I’m an author, writer, marketer, business owner and entrepreneur who specializes in agriculture. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com.

The Lytton Cooperative Creamery Association (featured in my Calhoun County book) was organized in June 1933. Capital for the new venture came from local farmers, who subscribed for shares on a basis of $5 per cow. In 1936, the creamery produced 110,000 pounds of butter. Grade A milk was processed, bottled, and distributed under the name “Lytton Maid” until this was discontinued in 1963. The plant closed in August 1979.

Recent Posts

- Do Press Releases Still Work?

- Erasing History? Budget Cuts Threaten to Gut Ag History at Iowa State University

- Machines that Changed America: John Froelich Invents the First Tractor in Iowa

- Bob Feller on Farming, Baseball and Military Service

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

Categories

- Achitecture

- Agriculture

- Architecture

- baking

- barbeque

- Barn

- breakfast

- Business

- Communication Tips

- Conservation

- content

- cooking

- Crime

- Dallas County

- Economical

- Farm

- Featured

- Food

- Food history

- health

- Iowa

- Iowa food

- Iowa history

- marketing

- Photography

- Recipes

- Seasonal

- Small town

- Storytelling

- Uncategorized

- writing

Archive by year

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- When Agriculture Entered the Long Depression in the Early 1920s

- The Corn Lady: Jessie Field Shambaugh and the Birth of 4-H in Iowa

- Sauce to Sanitizer: Cookies Food Products Bottles Hand Sanitizer Made with Ethanol

- Myth Busting: No, Your Pork Doesn't Come from China

- Long Live Print Newsletters! 5 Keys to Content Marketing Success

- Shattering Silence: Farmer Helped Slave Find Freedom and Racial Equality in Iowa

- Meet Iowa Farmer James Jordan, Underground Railroad Conductor

- George Washington Carver Rose from Slavery to Ag Scientist

- Remembering the African-American Sioux City Ghosts Fast-Pitch Softball Team

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- 2019

- The Untold Story of Iowa’s Ag Drainage Systems

- Stop Rumors Before They Ruin Your Brand

- Finding Your Voice: The Story You Never Knew About "I Have a Dream"

- Warm Up with Homemade Macaroni and Cheese Soup

- Can a True Story Well Told Turn You into a Tom Brady Fan?

- Baking is for Sharing: Best Bread, Grandma Ruby’s Cookies and Other Iowa Favorites

- 4 Key Lessons from Bud Light’s Super Bowl Corn-troversy

- Could Your Story Change Someone’s Life?

- What To Do When the Travel Channel Calls

- Tex-Mex Sloppy Joes and the Magic of Maid-Rite in Iowa

- How Not to Invite Someone to Your Next Event--and 3 Solutions

- We Need FFA: Iowa Ag Secretary Mike Naig Reflects on His FFA Experiences

- From My Kitchen to Yours: Comfort Food, Conversation and Living History Farms

- Smart Marketing Lessons from an Uber Driver--Listen Up!

- Hog Trailers to Humidors: Two New Iowa Convenience Stores Reflect “Waspy’s Way”

- A Dirty Tip to Make Your Social Media Content More Shareable

- Are You on Team Cinnamon Roll?

- Senator Grassley on Farming: Any Society is Only Nine Meals Away From a Revolution

- Why We Should Never Stop Asking Why

- What’s the Scoop? Expanded Wells’ Ice Cream Parlor Offers a Taste of Iowa

- Independence, Iowa’s Connection to the Titanic and Carpathia

- Memories of Carroll County, Iowa, Century Farm Endure

- Iowa's “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

- 2018

- How to Cook a Perfect Prime Rib

- How Did We Get So Rude?

- Mmm, Mmm Good: Soup’s on at the Rockwell City Fire Department

- Quit Using “Stupid Language”

- In Praise of Ham and Bean Soup

- Recalling a Most Unconventional—and Life-Changing--FFA Journey

- Events Spark Stories That Help Backcountry Winery Grow in Iowa

- Sac County Barn Quilt Attracts National Attention

- Doing Good, Eating Good at Lytton Town Night

- Young Entrepreneur Grows a Healthy Business in Small-Town Iowa

- Digging Deeper: Volunteers Showcase Thomas Jefferson Gardens in Iowa

- How to Tell Your Community’s Story—with Style!

- DNA Helps Sailor Killed at Pearl Harbor Return to His Family

- It’s Time to Be 20 Again: Take a Road Trip on Historic Highway 20

- The Biggest Reason You Shouldn’t Slash Your Marketing Budget in Tough Times

- Are You Telling a Horror Story of Your Business?

- Pieced Together: Barn Quilt Documentary Features Iowa Stories

- Unwrapping Storytelling Tips from the Candy Bomber

- Barn Helped Inspire Master Craftsman to Create Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

- Butter Sculptures to Christmas Ornaments: Waterloo Boy Tractor Celebrates 100 Years

- Ag-Vocating Worldwide: Top 10 Tips for Sharing Ag’s Story with Consumers

- 2017

- Growing with Grow: Iowa 4-H Leader Guides 100-Year-Old 4-H Club for 50 Years

- High-Octane Achiever: Ethanol Fuels New Driver Tiffany Poen

- Shakespeare Club Maintains 123 Years of Good Taste in Small-Town Iowa

- Iowa’s Ice Queen: Entrepreneur Caroline Fischer’s Legacy Endures at Hotel Julien Dubuque

- Darcy's Bill of Assertive Rights: How to Communicate and Get What You Need

- Celebrating Pi Day in Iowa with Old-Fashioned Chicken Pot Pie

- Cooking with Iowa’s Radio Homemakers

- Top 10 Tips to Find the Right Writer to Tell Your Company’s Stories

- The “No BS” Way to Protect Yourself from Rude, Obnoxious People

- Learning from the Land: 9 Surprising Ways Farmers Make Conservation a Priority

- Leftover Ham? Make This Amazing Crustless Spinach and Ham Quiche

- Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic

- Coming Soon--"Dallas County," a New Iowa History Book!

- How to Clean a Burned Pan in 6 Simple Steps

- Iowa Beef Booster: Larry Irwin Takes a New Twist on Burgers

- Get Your Grill On: How to Build a Better Burger

- "Thank God It’s Over:" Iowa Veteran Recalls the Final Days of World War 2

- How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service

- Imagine That! Writers, Put Your Reader Right in the Action

- Remembering Ambassador Branstad’s Legacy from the 1980s Farm Crisis in Iowa

- Busting the Iowa Butter Gang

- Lightner on Leadership: “Everyone Has Something to Give”

- Show Up, Speak Up, Don’t Give Up

- Small - Town Iowa Polo Teams Thrilled Depression - Era Crowd

- Ethanol:Passion by the Gallon

- Cruising Through Forgotten Iowa History on Lincoln Highway

- Why I'm Using a Powerful 500-Year-Old Technology to Make History--And You Can, Too

- 5 Ways a “History Head” Mindset Helps You Think Big

- Behind the Scene at Iowa's Own Market to Market

- Let’s Have an Iowa Potluck with a Side of History!

- Iconic State Fair Architecture: Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iconic State Fair Architecture- Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iowa Underground - How Coal Mining Fueled Dallas County's Growth

- Ultra-Local Eating: Jennifer Miller Guides CSA, Iowa Food Cooperative

- The Hotel Pattee and I are Hosting a Party—And You’re Invited!

- Tell Your Story—But How?

- Mediterranean Delights: Iowa Ag Influences Syrian-Lebanese Church Dinner

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations!

- 6 Ways to Motivate Yourself to Write—Even When You’re Not in the Mood

- Always Alert-How to Stay Safe in Any Situation

- Does Accuracy Even Matter Anymore?

- Soy Power Shines at Historic Rainbow Bridge

- Free Gifts! (Let’s Talk Listening, Stories and History)

- 2016

- How to Connect with Anyone: Lessons from a Tornado

- Soul Food: Lenten Luncheons Carry on 45-Year Iowa Tradition

- Top 3 Tips for Writing a Must-Read Article

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips to Better Writing

- Top 8 Tips for Building a Successful Freelance Business

- 10 Steps to Better Photos

- Reinventing the Marketer of 2010

- Extreme Writing Makeover

- My Top Social Media Tips for Farmers: REVEALED!

- Honoring the Legacy of Rural Iowa's Greatest Generation

- Iowa's Orphan Train Heritage

- Dedham’s Famous Bologna Turns 100: Kitt Family Offers a Taste of Iowa History

- Iowa Barn Honors Pioneer Stock Farm

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips for Better Photos

- Soup and Small-Town Iowa Spirit

- Savoring the Memories: Van's Café Served Up Comfort Food for Six Decades

- Mayday, Mayday—The Lost History of May Poles and May Baskets in Iowa

- Iowa's Vigilante Crime Fighters of the 1920s and 1930s

- Very Veggie: Iowan's Farm-Fresh Recipes Offer Guilt-Free Eating

- Iowa Public TV's "Market to Market" Features Expedition Yetter, Agri-Tourism, Des Moines Water Works' Lawsuit

- 62 Years and Counting: Calhoun County, Iowa, Families Maintain 4th of July Picnic Tradition

- “A Culinary History of Iowa” Satisfies: Iowa History Journal Book Review

- For the Love of Baking: Lake City's Ellis Family Showcases Favorite Iowa Farm Recipes (Caramel Rolls, Pumpkin Bars and More!)

- Remembering Sept. 11: Iowa Community’s Potluck Honors America

- Talking Iowa Food and Culinary History on Iowa Public Radio

- Talking "Stilettos in the Cornfield," Taxes, Trade and More on CNBC

- FarmHer #RootedinAg Spotlight--FFA Attracts More Women to Careers in Ag

- Rustic Cooking Refined: Iowan Robin Qualy Embraces Global Flavors

- Voice of Reason: Iowa Pork Producer Dave Struthers Offers Top 10 Tips to Speak Up for Ag

- Iowa Eats! Why Radio Iowa, Newspapers and Libraries are Hungry for "A Culinary History of Iowa"

- Iowa Turkeys Carry on National Thanksgiving Tradition

- Riding with Harry: 2016 Presidential Election Reflects Truman's Iowa Revival at 1948 Plowing Match in Dexter

- All Aboard! Rockwell City’s “Depot People” Offer a Taste of Iowa History

- Is This Iowa's Favorite Appetizer?

- O, Christmas Tree! Small Iowa Towns Celebrate with Trees in the Middle of the Street

- Slaves Escaped Through Dallas County on Iowa’s Underground Railroad

- Adel Barn Accents Penoach Winery in Iowa

- Celebrating New Year's Eve in Style at a Classic Iowa Ballroom