How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service

It shocked me the first time it happened. I was sitting in the living room of a World War 2 veteran and was interviewing him for a Memorial Day story. I felt humbled and grateful to hear his stories as he described the places he’d served, the hardships he had experienced, his fears and his perspective on life all these years later. What stunned me was his family’s reaction.

“That’s the first time I’ve heard most of those stories,” said his daughter who had stopped by during the interview.

This wouldn’t be the first time I’d have this experience. I’ve discovered that sometimes veterans won’t open up, even to loved ones, because the memories are too painful, but sometimes the reasons are much simpler. “I tried sharing these stories a few times, but my family didn’t really understand what I was talking about and didn’t ask any questions, so I just gave up,” one Iowa veteran told m e. “I decided it would be easier to talk about these things with other veterans.”

e. “I decided it would be easier to talk about these things with other veterans.”

This got me thinking—what’s the right way to talk to veterans, whether you want to thank them or hear more of their stories? If you’re like me, maybe you’re not even sure how to start the conversation.

That’s why I asked Marine Corps veterans James Nash and Jay Lippmeier for their insights. I first connected with Nash and Lippmeier after they came to Lakota, Iowa, for Hunting with Heroes. This amazing program, which was created by Bernie and Jason Becker, invites Marines from the Wounded Warrior Battalion at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, to the Midwest each November for an all-expenses-paid trip to find some peace in the Iowa countryside and enjoy some prime pheasant hunting.

Captain Nash is now retired from the Marine Corps and lives in Oregon. He enjoys returning to Iowa to help create a sense of camaraderie and comfort for the Marines who participate in Hunting with Heroes for the first time. Staff Sergeant Lippmeier, who participated in the 2016 Hunting with Heroes event, is a Cincinnati, Ohio, native who recently retired from the Marines Corps and appreciates the chance to spend more time with his family, including his children.

I’d like to thank Captain Nash and Staff Sergeant Lippmeier for their friendship and for letting me share their insights in my May 26, 2017, Farm News column, which I’m also sharing here:

Q: Any tips on what people can say to veterans to start the conversation?

Nash: When folks say thanks for your service, it does two things to me. I typically sense their gratitude, but I also sense that sometimes people issue that canned phrase to reassure their sense of patriotism to themselves, and they are not interested in what exactly it is they’re thanking me for.

When I talk to vets, I ask then what branch they were in and what their job was. Army vets often respond with a numerical designation for their military occupational specialty (MOS), like 11B. That’s fine, but ask what that means, where were they stationed, what unit did they serve with? Did they deploy? Do they still keep in touch with anyone they served with?

If these questions don’t begin a conversation, the veteran likely doesn’t want to talk. Respect that. That’s the time to end the conservation and say thank you. It won’t be hollow because, now you both know what you are thanking the veteran for.

Lippmeier: Treat veterans like other people you’ve just met. Ask them what they do/did in the military, like their branch of service and their military occupation. Then use follow-up questions, especially if you don’t understand the answers or certain verbiage the military uses. I would much rather explain something to someone than have them have no clue what I’m talking about.

Upon first meeting someone, most vets I know have no problem talking about what branch they were in or what job they did without going into a lot personal details. Most vets will start to open up a bit as they get more comfortable. If someone doesn’t want to talk about his or her service, respect that. Everyone has bad days sometimes.

Q: Are there any things people shouldn’t ask?

Nash: I don’t like when folks asked me how many people I killed. It’s not like I wrote hash marks in my journal. But if they do ask, that’s better than if they are afraid to ask. When I sense people don’t have the courage to ask about my experiences, it makes me compare that lack of courage to the bravery I witnessed in the men I served with. Then I wonder why we risked so much for that person’s freedom.

I remember that it’s always incumbent upon the brave to protect the fearful, for a few to sacrifice for the many, but it doesn’t feel good when I compare the fear of driving through a minefield, getting shot at by snipers or having mortars explode around me to someone’s fear of simply asking me what that was like.

Lippmeier: The number one question people shouldn’t ask is, “Have you ever killed anyone?” That is by far the question I ‘ve been asked the most, and it’s definitely a loaded question and a very personal one, as well.

Besides that, most vets will let you know if they don’t want to answer a certain question, or they may shut down if a question strikes a nerve. Again, just respect that and move on. I’m sure there are questions that would make anyone uncomfortable, so just use your best judgment and treat vets with the same respect you would treat any person you just met.

Q: Are there any things you wish people knew about the military or veterans?

Nash: Not every service member experiences combat. Most don’t. It’s important to not discount their sacrifice in the time they spend away from their loved ones and the relative hazards to their job. Also, when it comes to injuries, you must understand that paralysis and amputations are dramatic, but many injuries are unseen. A lot of folks look at me and say things like, “Well, it looks like you are doing just fine.” To which I think, yeah, it’s just my brain and spine that were damaged. No big deal. But I don’t say that.

Lippmeier: The biggest thing that I wish people knew is that everyone’s military experience will vary. Just because someone was in the military doesn’t mean they were in combat. The majority of veterans don’t see combat, but just because a vet wasn’t in combat doesn’t make their service less honorable. Without vets that didn’t see combat, the combat guys wouldn’t be able to do their jobs.

Another thing is that not all injuries are visible. You can spot guys who are missing limbs or using wheelchairs or other devices, but the majority of vets who are injured have “invisible wounds.” Just because I have 10 fingers and 10 toes doesn’t mean I don’t have five herniated discs, scar tissue in my brain, severe post-traumatic stress disorder, and a laundry list of other injuries. So just realize there can be a plethora of things going on with someone even though he or she looks ok.

Q: Any other tips for how civilians can communicate better with veterans?

Lippmeier: Treat veterans like normal people, but realize they’ve had a lot of different experiences than non-vets. Just be patient, and veterans will usually open up after some time. It’s sometimes hard for veterans to let someone in their life, because they may have seen or had someone close to them be violently torn from their life.

Nash: Know that if you ask these questions, the answers may make you uncomfortable. Try to compare your discomfort with the experience of the person you are speaking to, and hopefully it will give you the guts the hang in there and have the conversation. Let veterans know their sacrifices were worth the cost.

I salute our veterans

I salute America’s military men and women, including Captain Nash and Staff Sergeant Lippmeier, and am forever grateful to those who trust me enough to share their stories. We must never forget their service and their sacrifices. (Click here to hear Captain Nash, in his own words, talk about everything from hunting to his experiences as an officer to being awarded the Purple Heart.)

Some veterans will tell you that Veterans’ Day is the time to member those who survived, while Memorial Day is to honor those who have died. That’s true, yet Memorial Day to me means a time to honor all our military personnel, including those who have passed away, veterans who are still with us and those serving on active duty.

A respect for all veterans was instilled in me from childhood as my parents took me each May to the Lake City Cemetery for the Memorial Day service. The roll call of the deceased is one of the most poignant parts of the service. As I listen for the name Henry C. Nicholson, an ancestor of mine who fought in the Civil War, I also glance around the crowd and see the veterans who are still with us. These men and women are my friends and neighbors who came back to Iowa to farm, work hard, raise a family and give back to their community. These are the everyday people who make America work.

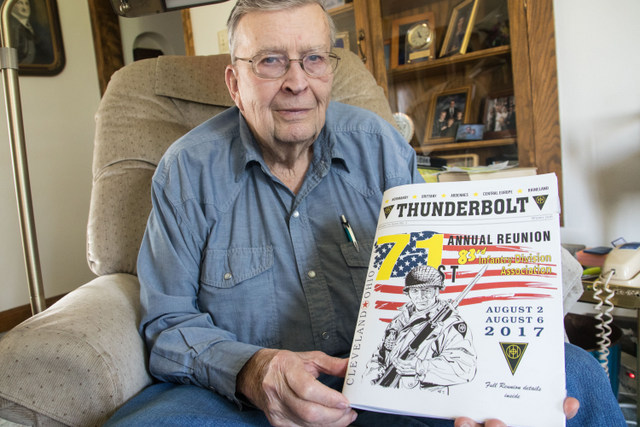

Harold Geisinger, 91, of Storm Lake, Iowa served in Europe in the U.S. Army during World War 2. This retired farmer continues to help on his family’s farm north of Storm Lake.

“Thank God it’s over”

Most of these veterans are humble, unassuming people, like Harold Geisinger of Storm Lake. I was honored to sit down with this World War 2 veteran this May. What started as as interview about his family’s Buena Vista County Century Farm turned into an unforgettable conversation about his service in the U.S. Army in the waning days of World War 2. Here’s a sample of his story, which I originally wrote for Farm News:

While V-E Day (Victory in Europe) was proclaimed “the celebration heard ‘round the world,” it was only a temporary reprieve for Harold Geisinger. This 19-year-old Iowa farm boy from Storm Lake was on his way to Le Havre, France, with the U.S. Army when Germany surrendered unconditionally to the Allies on May 7, 1945.

After a low-key celebration, Geisinger and his fellow soldiers boarded a box car in France bound for Hanover, Germany. Geisinger then joined a convoy in Bavaria, the section of Germany where American troops were guarding railroads, train depots, irrigation sites and more.

While the war was over in Europe, fighting continued on the other side of the globe. In the summer of 1945, there was talk that Geisinger and his fellow soldiers would likely be on board the next U.S. military ship bound for the Pacific Theater. Everything changed, however, when Japan surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945, following President Harry S. Truman’s orders to drop two atomic bombs on Japan in August 1945.

“When we got the word that Japan quit, we didn’t celebrate,” said Geisinger, 91, who still gets tears in his eyes when he thinks back to those days nearly 72 years ago. “We simply sat down and said, ‘Thank God it’s over.’”

Read off of Harold’s remarkable story here.

Want more?

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by and listening to these stories. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you want more Iowa stories, history and recipes, as well as tips to make you a better communicator. If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page. Let’s stay in touch.

P.S. Thanks for joining me. I’m glad you’re here.

@Copyright 2017 Darcy Maulsby & Co.

2 responses to “How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service”

Recent Posts

- Do Press Releases Still Work?

- Erasing History? Budget Cuts Threaten to Gut Ag History at Iowa State University

- Machines that Changed America: John Froelich Invents the First Tractor in Iowa

- Bob Feller on Farming, Baseball and Military Service

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

Categories

- Achitecture

- Agriculture

- Architecture

- baking

- barbeque

- Barn

- breakfast

- Business

- Communication Tips

- Conservation

- content

- cooking

- Crime

- Dallas County

- Economical

- Farm

- Featured

- Food

- Food history

- health

- Iowa

- Iowa food

- Iowa history

- marketing

- Photography

- Recipes

- Seasonal

- Small town

- Storytelling

- Uncategorized

- writing

Archive by year

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- When Agriculture Entered the Long Depression in the Early 1920s

- The Corn Lady: Jessie Field Shambaugh and the Birth of 4-H in Iowa

- Sauce to Sanitizer: Cookies Food Products Bottles Hand Sanitizer Made with Ethanol

- Myth Busting: No, Your Pork Doesn't Come from China

- Long Live Print Newsletters! 5 Keys to Content Marketing Success

- Shattering Silence: Farmer Helped Slave Find Freedom and Racial Equality in Iowa

- Meet Iowa Farmer James Jordan, Underground Railroad Conductor

- George Washington Carver Rose from Slavery to Ag Scientist

- Remembering the African-American Sioux City Ghosts Fast-Pitch Softball Team

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- 2019

- The Untold Story of Iowa’s Ag Drainage Systems

- Stop Rumors Before They Ruin Your Brand

- Finding Your Voice: The Story You Never Knew About "I Have a Dream"

- Warm Up with Homemade Macaroni and Cheese Soup

- Can a True Story Well Told Turn You into a Tom Brady Fan?

- Baking is for Sharing: Best Bread, Grandma Ruby’s Cookies and Other Iowa Favorites

- 4 Key Lessons from Bud Light’s Super Bowl Corn-troversy

- Could Your Story Change Someone’s Life?

- What To Do When the Travel Channel Calls

- Tex-Mex Sloppy Joes and the Magic of Maid-Rite in Iowa

- How Not to Invite Someone to Your Next Event--and 3 Solutions

- We Need FFA: Iowa Ag Secretary Mike Naig Reflects on His FFA Experiences

- From My Kitchen to Yours: Comfort Food, Conversation and Living History Farms

- Smart Marketing Lessons from an Uber Driver--Listen Up!

- Hog Trailers to Humidors: Two New Iowa Convenience Stores Reflect “Waspy’s Way”

- A Dirty Tip to Make Your Social Media Content More Shareable

- Are You on Team Cinnamon Roll?

- Senator Grassley on Farming: Any Society is Only Nine Meals Away From a Revolution

- Why We Should Never Stop Asking Why

- What’s the Scoop? Expanded Wells’ Ice Cream Parlor Offers a Taste of Iowa

- Independence, Iowa’s Connection to the Titanic and Carpathia

- Memories of Carroll County, Iowa, Century Farm Endure

- Iowa's “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

- 2018

- How to Cook a Perfect Prime Rib

- How Did We Get So Rude?

- Mmm, Mmm Good: Soup’s on at the Rockwell City Fire Department

- Quit Using “Stupid Language”

- In Praise of Ham and Bean Soup

- Recalling a Most Unconventional—and Life-Changing--FFA Journey

- Events Spark Stories That Help Backcountry Winery Grow in Iowa

- Sac County Barn Quilt Attracts National Attention

- Doing Good, Eating Good at Lytton Town Night

- Young Entrepreneur Grows a Healthy Business in Small-Town Iowa

- Digging Deeper: Volunteers Showcase Thomas Jefferson Gardens in Iowa

- How to Tell Your Community’s Story—with Style!

- DNA Helps Sailor Killed at Pearl Harbor Return to His Family

- It’s Time to Be 20 Again: Take a Road Trip on Historic Highway 20

- The Biggest Reason You Shouldn’t Slash Your Marketing Budget in Tough Times

- Are You Telling a Horror Story of Your Business?

- Pieced Together: Barn Quilt Documentary Features Iowa Stories

- Unwrapping Storytelling Tips from the Candy Bomber

- Barn Helped Inspire Master Craftsman to Create Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

- Butter Sculptures to Christmas Ornaments: Waterloo Boy Tractor Celebrates 100 Years

- Ag-Vocating Worldwide: Top 10 Tips for Sharing Ag’s Story with Consumers

- 2017

- Growing with Grow: Iowa 4-H Leader Guides 100-Year-Old 4-H Club for 50 Years

- High-Octane Achiever: Ethanol Fuels New Driver Tiffany Poen

- Shakespeare Club Maintains 123 Years of Good Taste in Small-Town Iowa

- Iowa’s Ice Queen: Entrepreneur Caroline Fischer’s Legacy Endures at Hotel Julien Dubuque

- Darcy's Bill of Assertive Rights: How to Communicate and Get What You Need

- Celebrating Pi Day in Iowa with Old-Fashioned Chicken Pot Pie

- Cooking with Iowa’s Radio Homemakers

- Top 10 Tips to Find the Right Writer to Tell Your Company’s Stories

- The “No BS” Way to Protect Yourself from Rude, Obnoxious People

- Learning from the Land: 9 Surprising Ways Farmers Make Conservation a Priority

- Leftover Ham? Make This Amazing Crustless Spinach and Ham Quiche

- Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic

- Coming Soon--"Dallas County," a New Iowa History Book!

- How to Clean a Burned Pan in 6 Simple Steps

- Iowa Beef Booster: Larry Irwin Takes a New Twist on Burgers

- Get Your Grill On: How to Build a Better Burger

- "Thank God It’s Over:" Iowa Veteran Recalls the Final Days of World War 2

- How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service

- Imagine That! Writers, Put Your Reader Right in the Action

- Remembering Ambassador Branstad’s Legacy from the 1980s Farm Crisis in Iowa

- Busting the Iowa Butter Gang

- Lightner on Leadership: “Everyone Has Something to Give”

- Show Up, Speak Up, Don’t Give Up

- Small - Town Iowa Polo Teams Thrilled Depression - Era Crowd

- Ethanol:Passion by the Gallon

- Cruising Through Forgotten Iowa History on Lincoln Highway

- Why I'm Using a Powerful 500-Year-Old Technology to Make History--And You Can, Too

- 5 Ways a “History Head” Mindset Helps You Think Big

- Behind the Scene at Iowa's Own Market to Market

- Let’s Have an Iowa Potluck with a Side of History!

- Iconic State Fair Architecture: Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iconic State Fair Architecture- Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iowa Underground - How Coal Mining Fueled Dallas County's Growth

- Ultra-Local Eating: Jennifer Miller Guides CSA, Iowa Food Cooperative

- The Hotel Pattee and I are Hosting a Party—And You’re Invited!

- Tell Your Story—But How?

- Mediterranean Delights: Iowa Ag Influences Syrian-Lebanese Church Dinner

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations!

- 6 Ways to Motivate Yourself to Write—Even When You’re Not in the Mood

- Always Alert-How to Stay Safe in Any Situation

- Does Accuracy Even Matter Anymore?

- Soy Power Shines at Historic Rainbow Bridge

- Free Gifts! (Let’s Talk Listening, Stories and History)

- 2016

- How to Connect with Anyone: Lessons from a Tornado

- Soul Food: Lenten Luncheons Carry on 45-Year Iowa Tradition

- Top 3 Tips for Writing a Must-Read Article

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips to Better Writing

- Top 8 Tips for Building a Successful Freelance Business

- 10 Steps to Better Photos

- Reinventing the Marketer of 2010

- Extreme Writing Makeover

- My Top Social Media Tips for Farmers: REVEALED!

- Honoring the Legacy of Rural Iowa's Greatest Generation

- Iowa's Orphan Train Heritage

- Dedham’s Famous Bologna Turns 100: Kitt Family Offers a Taste of Iowa History

- Iowa Barn Honors Pioneer Stock Farm

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips for Better Photos

- Soup and Small-Town Iowa Spirit

- Savoring the Memories: Van's Café Served Up Comfort Food for Six Decades

- Mayday, Mayday—The Lost History of May Poles and May Baskets in Iowa

- Iowa's Vigilante Crime Fighters of the 1920s and 1930s

- Very Veggie: Iowan's Farm-Fresh Recipes Offer Guilt-Free Eating

- Iowa Public TV's "Market to Market" Features Expedition Yetter, Agri-Tourism, Des Moines Water Works' Lawsuit

- 62 Years and Counting: Calhoun County, Iowa, Families Maintain 4th of July Picnic Tradition

- “A Culinary History of Iowa” Satisfies: Iowa History Journal Book Review

- For the Love of Baking: Lake City's Ellis Family Showcases Favorite Iowa Farm Recipes (Caramel Rolls, Pumpkin Bars and More!)

- Remembering Sept. 11: Iowa Community’s Potluck Honors America

- Talking Iowa Food and Culinary History on Iowa Public Radio

- Talking "Stilettos in the Cornfield," Taxes, Trade and More on CNBC

- FarmHer #RootedinAg Spotlight--FFA Attracts More Women to Careers in Ag

- Rustic Cooking Refined: Iowan Robin Qualy Embraces Global Flavors

- Voice of Reason: Iowa Pork Producer Dave Struthers Offers Top 10 Tips to Speak Up for Ag

- Iowa Eats! Why Radio Iowa, Newspapers and Libraries are Hungry for "A Culinary History of Iowa"

- Iowa Turkeys Carry on National Thanksgiving Tradition

- Riding with Harry: 2016 Presidential Election Reflects Truman's Iowa Revival at 1948 Plowing Match in Dexter

- All Aboard! Rockwell City’s “Depot People” Offer a Taste of Iowa History

- Is This Iowa's Favorite Appetizer?

- O, Christmas Tree! Small Iowa Towns Celebrate with Trees in the Middle of the Street

- Slaves Escaped Through Dallas County on Iowa’s Underground Railroad

- Adel Barn Accents Penoach Winery in Iowa

- Celebrating New Year's Eve in Style at a Classic Iowa Ballroom

Wise advice.

Thanks so much, Joy. I went to the experts on this, and they shared priceless insights.