Iowa’s “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

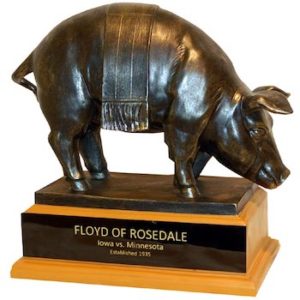

If you follow college football in the Midwest, especially if you’re a University of Iowa Hawkeye football fan, you may know the story of Floyd of Rosedale. A bronze statue of the pig, Floyd of Rosedale, is exchanged between the two states. The original pig himself came from Rosedale Farms at Fort Dodge in north-central Iowa.

The whole deal emerged from a bet between Iowa Governor Clyde Herring and Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson about the outcome of the 1935 Iowa-Minnesota football game, but this story involves something much deeper than a famous pig and a bronze trophy.

The problem started the previous year, on Saturday, October 27, 1934, when rough play was directed towards one Iowa Hawkeye running back, Ozzie Simmons. Simmons was a rarity in that era: a black player on a major college football team. Dubbed the “ebony eel” by some sportswriters of the era, Simmons had come north to play football when he wasn’t allowed to play football in his home state of Texas, due to his race.

America in the 1930s included Jim Crow laws in southern states, which segregated blacks from whites. In northern states, no such laws existed, but discrimination was still widespread.

Simmons’ talent couldn’t be denied, however, and he attracted the attention of a young Iowa sports broadcaster perched high above the field. That broadcaster, who would become President Ronald Reagan, became an Ozzie Simmons fan, noted Minnesota Public Radio (MPR), which aired the story “The Origin of Floyd of Rosedale” in 2005. Reagan described a trademark Simmons’ move during a telephone interview with legendary Iowa sports broadcaster Jim Zabel of WHO Radio in Des Moines.

“Ozzie would come up to a man, and instead of a stiff-arm or sidestep or something, Ozzie — holding the football in one hand — would stick the football out,” Reagan said. “And the defensive man just instinctively would grab at the ball. Ozzie would pull it away from him and go around him.”

There were no dazzling runs against Minnesota, however, in the 1934 game at Iowa. Simmons was knocked out three times, leaving the game for good by halftime. The Gophers overwhelmed Simmons and the rest of the Iowa team, beating them 48-12.

While Minnesota went on to win the national championship that year, Iowa fans at the game were outraged by how Minnesota played, in Iowa City claiming the defense deliberately went after Iowa Simmons hard. (Just 11 years earlier, Iowa State’s first black athlete, Jack Trice, died of injuries sustained in a game at Minnesota in 1923.)

How Floyd of Rosedale was born

In 1935, the Rosedale Trophy debuted in an attempt to generate some goodwill between the two schools. Ahead of the 1935 game, Herring warned Minnesota not to pull the same stunts it did the year before. “If the officials stand for any rough tactics like Minnesota used last year, I’m sure the crowd won’t,” Herring said.

Olson sent a telegram to Governor Herring to assure him that the Minnesota team would tackle clean. To help calm the growing tension ahead of the next Minnesota-Iowa football game, Olson also went on to say that he would bet a prize pig from Minnesota against a prize pig from Iowa that Minnesota would win the big game. The loser would have to deliver the pig in person.

“Dear Clyde,” stated Olson’s telegram to Herring. “Minnesota folks are excited over your statement about the Iowa crowd lynching the Minnesota football team. If you seriously think Iowa has any chance to win, I will bet you a Minnesota prize hog against an Iowa prize hog that Minnesota wins today.”

The Iowa governor accepted, and what became known as the Floyd of Rosedale prize was born. Herring apparently followed Olson’s cue. He joked it would be hard to find a prize hog in Minnesota, since they all were so “scrawny.”

Floyd of Rosedale trophy

Word of the bet reached Iowa City as the crowd gathered at the stadium. Things calmed down, and the game proceeded without incident. Minnesota won 13-7.

The prize pig from Iowa was a Hampshire boar, black with a white belt. He was later named the Floyd of Rosedale after Minnesota’s governor. In the week following the big game, Herring delivered the live pig to the Minnesota Capitol building in St. Paul and took Floyd inside to meet Olson.

After the hog’s trophy days were over, Floyd spent his remaining days on a farm in southeast Minnesota. Floyd died of hog cholera in July 1936, about eight months after he made the front page. The real Floyd, Governor Olson, passed away less than a month later, dying of cancer in August 1936.

(Ironically, Floyd the hog wasn’t the only celebrity in his family. Floyd of Rosedale was the brother of another famous boar, Blue Boy, who had appeared in the 1933 movie “State Fair.”)

Leaving a legacy

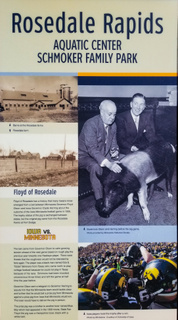

All these years later, the famous Floyd of Rosedale endures as one of college football’s most famous trophies. Floyd of Rosedale’s legacy is also preserved in a marker by the Rosedale Rapids Aquatic Center in Fort Dodge.

Simmons, whose story prompted the Floyd of Rosedale trophy, never took much interest in the trophy, in part because of the era of racial discrimination it recalled. He was denied a chance to play professional football, because the National Football League banned black players at the time, noted MPR. He played some minor league ball, joined the Navy and eventually became a Chicago public school teacher.

“When Ozzie Simmons stepped onto the field in October, 1934, to play Minnesota, he entered a national drama that’s still playing out today,” MPR noted. “All Simmons wanted was a chance. The trophy is an ever-present reminder of how precious that right is.”

Want more stories like this?

These are the kinds of stories I’m sharing in my new book, “Iowa Agriculture: A History of Farming, Family and Food,” which was released by The History Press on Monday, April 27, 2020. Order your signed copy by clicking here to my online store.

One more thing–the story of illegal gambling

After I posted this story, I received this intriguing email from my friend Victoria Herring of Des Moines:

“You may remember coming to Artisan Gallery 218 to do book talks. I was reading your website about the Floyd of Rosedale story – apparently appearing in an upcoming book. I assume you know there’s a bit more to the story == I think George Mills wrote about it in one of his books == when this happened some guy [whose name I forget but he was a bit of a thorn in the side of some public figures] filed a criminal complaint against Gov. Herring [he was my grandfather] alleging illegal betting — might be an interesting even if a little off topic addition.”

I pulled out a copy of George Mills’ classic book, Looking in Windows: Surprising Stories of Old Des Moines, and saw exactly what Victoria was talking about. In the second called “A Governor Arrested,” Mills explained how a gadfly named Virgil Case in Des Moines got a warrant for Governor Herring’s arrest following the Floyd of Rosedale 1935 bet. The charge? Gambling on a hog wager.

At the time, Iowa law provided a penalty of up to a $100 fine or 30 days in jail for gambling. Municipal Judge J.E. Mershon signed the warrant.

Who was Case and why did he go to all this trouble? He was a “natural-born hell raiser,” wrote Mils, who added that Case had been a secretary to a Des Moines mayor and publisher of a weekly newspaper.

Case explained how he happened to file the charge. He said he had some spare time, and it occurred to him a “good way to put in that time was to go over to Municipal Court and have the governor arrested. So that’s what I did.” He said his profession was “raising hell with public officials because they should be the first to set a good example.”

Word of the warrant reached Herring while he was still with Minnesota Governor Olson in Minneapolis. Herring immediately engaged Olson as his attorney. Olson squelched a suggestion that the pig be auctioned off to pay a possible Herring fine. “That pig stays in Minnesota, regardless of what happens,” Olson declared. He added that the bet wasn’t a gamble anyway, since Minnesota was a cinch to win the game.

Olson suggested that Herring stay in St. Paul, where he couldn’t be extradited, since the Minnesota governor had to consent to the extradition, and Olson was already Herring’s attorney. Herring observed that only the governor of Iowa could extradite anyone back to Iowa–and he was the governor of Iowa.

“Olson added a sly insult when he said it wasn’t gambling because ‘nothing of value was involved,'” Mills wrote. Herring shot back that Floyd of Rosedale was a “right good hog.”

Walter Brick, deputy municipal court bailiff, cause a stir of excitement at the Iowa statehouse a few days later. When he showed up at Herring’s office, reporters thought maybe he was there to lead the governor away in handcuffs. Nope. Brick just wanted to talk over a planned court hearing on the charge.

The only action the deputy took that day was to join the reporters in eating apples out of Herring’s fruit basket. (“Beside apples, Herring was known at times to shut the door and provide the press with beer and Pella bologna, something no governor has done since,” Mills wrote.)

In the hearing, reporters and others testified that Herring hadn’t committed the so-called offense in Des Moines, that the bet wasn’t complete until Herring and Olson met in Iowa City. Assistant Polk County Attorney C. Edwin Moore, later chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court, moved that the case be dismissed. Judge Mershon was glad to do so. “The folderol was over,” Mills concluded.

Want more?

Thanks for stopping by. I invite you to read more of my blog posts if you value intriguing Iowa stories and history, along with Iowa food, agriculture updates, recipes and tips to make you a better

If you’re hungry for more stories of Iowa history, check out my top-selling “Culinary History of Iowa: Sweet Corn, Pork Tenderloins, Maid-Rites and More” book from The History Press. Also take a look at my latest book, “Dallas County,” and my “Calhoun County” book from Arcadia Publishing. Both are filled with vintage photos and compelling stories that showcase he history of small-town and rural Iowa. Order your signed copies today! Iowa postcards are available in my online store, too.

If you like what you see and want to be notified when I post new stories, be sure to click on the “subscribe to blog updates/newsletter” button at the top of this page, or click here. Feel free to share this with friends and colleagues who might be interested, too.

Also, if you or someone you know could use my writing services (I’m not only Iowa’s storyteller, but a professionally-trained journalist with 20 years of experience), let’s talk. I work with businesses and organizations within Iowa and across the country to unleash the power of great storytelling to define their brand and connect with their audience through clear, compelling blog posts, articles, news releases, feature stories, newsletter articles, social media, video scripts, and photography. Learn more at www.darcymaulsby.com, or e-mail me at yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Let’s stay in touch. I’m at darcy@darcymaulsby.com, and yettergirl@yahoo.com.

Talk to you soon!

Darcy

One response to “Iowa’s “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions”

Recent Posts

- Do Press Releases Still Work?

- Erasing History? Budget Cuts Threaten to Gut Ag History at Iowa State University

- Machines that Changed America: John Froelich Invents the First Tractor in Iowa

- Bob Feller on Farming, Baseball and Military Service

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

Categories

- Achitecture

- Agriculture

- Architecture

- baking

- barbeque

- Barn

- breakfast

- Business

- Communication Tips

- Conservation

- content

- cooking

- Crime

- Dallas County

- Economical

- Farm

- Featured

- Food

- Food history

- health

- Iowa

- Iowa food

- Iowa history

- marketing

- Photography

- Recipes

- Seasonal

- Small town

- Storytelling

- Uncategorized

- writing

Archive by year

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- When Agriculture Entered the Long Depression in the Early 1920s

- The Corn Lady: Jessie Field Shambaugh and the Birth of 4-H in Iowa

- Sauce to Sanitizer: Cookies Food Products Bottles Hand Sanitizer Made with Ethanol

- Myth Busting: No, Your Pork Doesn't Come from China

- Long Live Print Newsletters! 5 Keys to Content Marketing Success

- Shattering Silence: Farmer Helped Slave Find Freedom and Racial Equality in Iowa

- Meet Iowa Farmer James Jordan, Underground Railroad Conductor

- George Washington Carver Rose from Slavery to Ag Scientist

- Remembering the African-American Sioux City Ghosts Fast-Pitch Softball Team

- Want to Combat Fake News? Become a Better Researcher

- Classic Restaurants of Des Moines: A Taste of Thailand Served the "Publics" and Politics

- 2019

- The Untold Story of Iowa’s Ag Drainage Systems

- Stop Rumors Before They Ruin Your Brand

- Finding Your Voice: The Story You Never Knew About "I Have a Dream"

- Warm Up with Homemade Macaroni and Cheese Soup

- Can a True Story Well Told Turn You into a Tom Brady Fan?

- Baking is for Sharing: Best Bread, Grandma Ruby’s Cookies and Other Iowa Favorites

- 4 Key Lessons from Bud Light’s Super Bowl Corn-troversy

- Could Your Story Change Someone’s Life?

- What To Do When the Travel Channel Calls

- Tex-Mex Sloppy Joes and the Magic of Maid-Rite in Iowa

- How Not to Invite Someone to Your Next Event--and 3 Solutions

- We Need FFA: Iowa Ag Secretary Mike Naig Reflects on His FFA Experiences

- From My Kitchen to Yours: Comfort Food, Conversation and Living History Farms

- Smart Marketing Lessons from an Uber Driver--Listen Up!

- Hog Trailers to Humidors: Two New Iowa Convenience Stores Reflect “Waspy’s Way”

- A Dirty Tip to Make Your Social Media Content More Shareable

- Are You on Team Cinnamon Roll?

- Senator Grassley on Farming: Any Society is Only Nine Meals Away From a Revolution

- Why We Should Never Stop Asking Why

- What’s the Scoop? Expanded Wells’ Ice Cream Parlor Offers a Taste of Iowa

- Independence, Iowa’s Connection to the Titanic and Carpathia

- Memories of Carroll County, Iowa, Century Farm Endure

- Iowa's “Peacemaker Pig” Floyd of Rosedale Helped Calm Racial Tensions

- 2018

- How to Cook a Perfect Prime Rib

- How Did We Get So Rude?

- Mmm, Mmm Good: Soup’s on at the Rockwell City Fire Department

- Quit Using “Stupid Language”

- In Praise of Ham and Bean Soup

- Recalling a Most Unconventional—and Life-Changing--FFA Journey

- Events Spark Stories That Help Backcountry Winery Grow in Iowa

- Sac County Barn Quilt Attracts National Attention

- Doing Good, Eating Good at Lytton Town Night

- Young Entrepreneur Grows a Healthy Business in Small-Town Iowa

- Digging Deeper: Volunteers Showcase Thomas Jefferson Gardens in Iowa

- How to Tell Your Community’s Story—with Style!

- DNA Helps Sailor Killed at Pearl Harbor Return to His Family

- It’s Time to Be 20 Again: Take a Road Trip on Historic Highway 20

- The Biggest Reason You Shouldn’t Slash Your Marketing Budget in Tough Times

- Are You Telling a Horror Story of Your Business?

- Pieced Together: Barn Quilt Documentary Features Iowa Stories

- Unwrapping Storytelling Tips from the Candy Bomber

- Barn Helped Inspire Master Craftsman to Create Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

- Butter Sculptures to Christmas Ornaments: Waterloo Boy Tractor Celebrates 100 Years

- Ag-Vocating Worldwide: Top 10 Tips for Sharing Ag’s Story with Consumers

- 2017

- Growing with Grow: Iowa 4-H Leader Guides 100-Year-Old 4-H Club for 50 Years

- High-Octane Achiever: Ethanol Fuels New Driver Tiffany Poen

- Shakespeare Club Maintains 123 Years of Good Taste in Small-Town Iowa

- Iowa’s Ice Queen: Entrepreneur Caroline Fischer’s Legacy Endures at Hotel Julien Dubuque

- Darcy's Bill of Assertive Rights: How to Communicate and Get What You Need

- Celebrating Pi Day in Iowa with Old-Fashioned Chicken Pot Pie

- Cooking with Iowa’s Radio Homemakers

- Top 10 Tips to Find the Right Writer to Tell Your Company’s Stories

- The “No BS” Way to Protect Yourself from Rude, Obnoxious People

- Learning from the Land: 9 Surprising Ways Farmers Make Conservation a Priority

- Leftover Ham? Make This Amazing Crustless Spinach and Ham Quiche

- Iowa’s Lost History from the Titanic

- Coming Soon--"Dallas County," a New Iowa History Book!

- How to Clean a Burned Pan in 6 Simple Steps

- Iowa Beef Booster: Larry Irwin Takes a New Twist on Burgers

- Get Your Grill On: How to Build a Better Burger

- "Thank God It’s Over:" Iowa Veteran Recalls the Final Days of World War 2

- How to Thank Veterans for Their Military Service

- Imagine That! Writers, Put Your Reader Right in the Action

- Remembering Ambassador Branstad’s Legacy from the 1980s Farm Crisis in Iowa

- Busting the Iowa Butter Gang

- Lightner on Leadership: “Everyone Has Something to Give”

- Show Up, Speak Up, Don’t Give Up

- Small - Town Iowa Polo Teams Thrilled Depression - Era Crowd

- Ethanol:Passion by the Gallon

- Cruising Through Forgotten Iowa History on Lincoln Highway

- Why I'm Using a Powerful 500-Year-Old Technology to Make History--And You Can, Too

- 5 Ways a “History Head” Mindset Helps You Think Big

- Behind the Scene at Iowa's Own Market to Market

- Let’s Have an Iowa Potluck with a Side of History!

- Iconic State Fair Architecture: Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iconic State Fair Architecture- Historic Buildings Reflect Decades of Memories

- Iowa Underground - How Coal Mining Fueled Dallas County's Growth

- Ultra-Local Eating: Jennifer Miller Guides CSA, Iowa Food Cooperative

- The Hotel Pattee and I are Hosting a Party—And You’re Invited!

- Tell Your Story—But How?

- Mediterranean Delights: Iowa Ag Influences Syrian-Lebanese Church Dinner

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations

- 6 Steps for More Effective and Less Confrontational Conversations!

- 6 Ways to Motivate Yourself to Write—Even When You’re Not in the Mood

- Always Alert-How to Stay Safe in Any Situation

- Does Accuracy Even Matter Anymore?

- Soy Power Shines at Historic Rainbow Bridge

- Free Gifts! (Let’s Talk Listening, Stories and History)

- 2016

- How to Connect with Anyone: Lessons from a Tornado

- Soul Food: Lenten Luncheons Carry on 45-Year Iowa Tradition

- Top 3 Tips for Writing a Must-Read Article

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips to Better Writing

- Top 8 Tips for Building a Successful Freelance Business

- 10 Steps to Better Photos

- Reinventing the Marketer of 2010

- Extreme Writing Makeover

- My Top Social Media Tips for Farmers: REVEALED!

- Honoring the Legacy of Rural Iowa's Greatest Generation

- Iowa's Orphan Train Heritage

- Dedham’s Famous Bologna Turns 100: Kitt Family Offers a Taste of Iowa History

- Iowa Barn Honors Pioneer Stock Farm

- Darcy's Top 10 Tips for Better Photos

- Soup and Small-Town Iowa Spirit

- Savoring the Memories: Van's Café Served Up Comfort Food for Six Decades

- Mayday, Mayday—The Lost History of May Poles and May Baskets in Iowa

- Iowa's Vigilante Crime Fighters of the 1920s and 1930s

- Very Veggie: Iowan's Farm-Fresh Recipes Offer Guilt-Free Eating

- Iowa Public TV's "Market to Market" Features Expedition Yetter, Agri-Tourism, Des Moines Water Works' Lawsuit

- 62 Years and Counting: Calhoun County, Iowa, Families Maintain 4th of July Picnic Tradition

- “A Culinary History of Iowa” Satisfies: Iowa History Journal Book Review

- For the Love of Baking: Lake City's Ellis Family Showcases Favorite Iowa Farm Recipes (Caramel Rolls, Pumpkin Bars and More!)

- Remembering Sept. 11: Iowa Community’s Potluck Honors America

- Talking Iowa Food and Culinary History on Iowa Public Radio

- Talking "Stilettos in the Cornfield," Taxes, Trade and More on CNBC

- FarmHer #RootedinAg Spotlight--FFA Attracts More Women to Careers in Ag

- Rustic Cooking Refined: Iowan Robin Qualy Embraces Global Flavors

- Voice of Reason: Iowa Pork Producer Dave Struthers Offers Top 10 Tips to Speak Up for Ag

- Iowa Eats! Why Radio Iowa, Newspapers and Libraries are Hungry for "A Culinary History of Iowa"

- Iowa Turkeys Carry on National Thanksgiving Tradition

- Riding with Harry: 2016 Presidential Election Reflects Truman's Iowa Revival at 1948 Plowing Match in Dexter

- All Aboard! Rockwell City’s “Depot People” Offer a Taste of Iowa History

- Is This Iowa's Favorite Appetizer?

- O, Christmas Tree! Small Iowa Towns Celebrate with Trees in the Middle of the Street

- Slaves Escaped Through Dallas County on Iowa’s Underground Railroad

- Adel Barn Accents Penoach Winery in Iowa

- Celebrating New Year's Eve in Style at a Classic Iowa Ballroom

I happy that the “Floyd” story was made public again. I was Iowa born and Corn fed and now live in Maryland. I heard this story in my youth and I don’t think any of the younger generation knows of it. Will be very interested in your book when finished. Thank You

Laird Moulds formally of Lake City. Iowa in Calhoun County. Iowa